Dutch economy in focus: Recovery will take place in the second half of 2021

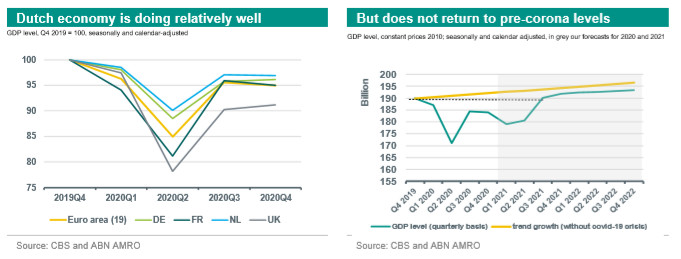

So far, the Dutch economy is weathering the storm relatively well. Compared to neighbouring countries, the GDP contraction of 2020 has been limited to 3.8% and, thanks to generous support, unemployment and bankruptcies have remained surprisingly low. But we are not there yet. The Dutch vaccination programme will only allow for a serious easing of restrictions from June onwards, so the economy will suffer a further blow in the first half of 2021. As soon as the economy reopens, fiscal support will also be phased out gradually. The economy will need time to adjust and in the meantime more companies will go bankrupt and workers will lose their jobs. At the same time, consumers will start to spend their involuntary savings, which have been build-up during the lockdown periods.. This will boost growth rates, although not as much as some may hope. We expect the economy to return to pre-corona GDP levels at the end of 2021. After that, catch-up growth will be meagre and growth will soon return to pre-corona levels. Taken together, we expect the output gap to remain negative throughout the forecasting horizon.

Co-authors: Nora Neuteboom and Piet Rietman

The Netherlands did relatively well

Dutch GDP held up better than many expected in Q4, despite the extended lockdown measures. After the Dutch economy experienced a strong rebound in the third quarter of last year (GDP growth of 7.8% quarter-on-quarter), according to the preliminary estimate, GDP contracted by only 0.1% qoq in the fourth quarter. This mild contraction was mostly due depressed services and retail sales. On balance, compared to the fourth quarter of 2019, the GDP level was 3% lower. The Netherlands performed relatively well, as the gap was 4% for Germany and almost 9% for the UK (see the chart below).

Recovery in 2021 depends on the roll-out of the vaccination programme

Although the Netherlands has weathered the covid-19 storm well, past results are no guarantee for the future. The ‘second wave’ started relatively early in the Netherlands and is still ongoing. Since December 15, a hard lockdown has been in force. Museums and theatres, amusement parks and zoos, casinos and saunas, indoor sports facilities, restaurants and hotels have all been closed. Non-essential shops are also closed. Based on the government’s vaccination timeline, we have drawn up a scenario for the economy. We assume that the current lockdown continues until early June. Only from June onwards, we expect that the elderly population is vaccinated to such an extent that measures can actually be released. We expect shops to reopen in June and restaurants/bars to reopen in July. In the months before, some restrictions, such as the curfew or the closure of schools and universities, may be eased earlier. But these measures have relatively little impact on the economy. As long as restrictions are in place, we think the government will continue its support measures. Our forecasts anticipate a gradual withdrawal of support measures from mid-2021.

Another dip in the first half of 2021, followed by a strong upswing

In the first quarter of this year, we expect a sharp contraction of 2,7% qoq. This decline is mainly driven by the fall in consumer spending. The expected contraction is mild compared to the first ‘intelligent’ lockdown in the second quarter of 2020. At the time, the Dutch economy contracted by 8,5%. The fact that the contraction is now less severe than during the first lockdown, even though tighter restrictions are in place, is because consumption has already fallen sharply. Indeed, many sectors were already partially closed in the summer, therefore consumer spending falls from a lower level. Also, contrary to the first lockdown, investments and exports are keeping the economy afloat. During the first wave, world trade dropped significantly. Production chains were disrupted across the globe and industrial production . As a result, Dutch exports and investments fell by 13% and 11% respectively. But when the factories in China reopened, global industrial production – and world trade subsequently – picked up fast. Currently, there are still some obstacles such as shortages of transport containers and memory chips, but this does not cause major disruptions in world trade.

As said, we assume that a number of restrictions will remain in place in the second quarter. Therefore, we foresee only a moderate recovery in the second quarter. GDP will growth by 0.8% compared to the first quarter in 2021. The real recovery will start in the second half of 2021. We expect GDP to growth by 5.2% and 1% in the third and fourth quarter respectively. This recovery will be mostly driven by a (statistical) rebound in consumer spending and investment (see for a detailed story on the subcomponents of GDP). All in all, we expect the economy to grow by 2.1% in 2021. This recovery is too small to make up for the previous GDP loss.

The scars of the crisis will only become visible when the economy opens up again

The number of bankruptcies has so far remained surprisingly low. For example, from 2015 to 2019, a period of strong economy growth, the number of companies that went bankrupt each quarter averaged around 1,000 (see figure below). In 2020, this number dropped to 800, despite the historic economic contraction of 3.8%. This low number of bankruptcies however does not tell the full story. In fact, the number of voluntary business closures in 2020 was higher than during the period 2015 to 2019. This means that a significant number of entrepreneurs have decided to quit . Furthermore, it usually takes some time before a contraction in GDP leads to an increase in bankruptcies. The main reason why the number of bankruptcies is at a historically low level is the generous stimulus package provided by the government. They have been able to dampen the rise in insolvencies so far. We therefore expect insolvencies to remain relatively low until the support measures are withdrawn.

But bankruptcies will likely increase in 2021

The gradual withdrawal of support measures from the third quarter of 2021 will lead to more bankruptcies. A large part of the government support was liquidity support in the form of tax deferrals. Moreover, in the supply chain, for example, suppliers and banks have also granted payment holidays. For some entrepreneurs, the burden of debt will be too large compared to the income streams. We expect a gradual increase in the number of bankruptcies from the third quarter of 2021 onwards, with a peak around the spring of 2022. We expect this peak to be around 1,500. This is equivalent to the average number of bankruptcies over the past 10 years. In the quarters following this peak, the number of insolvencies will decrease to a level comparable to the pre-corona situation.

The recent drop in unemployment is likely a temporary phenomenon

The corona crisis came at a time when the Netherlands was experiencing severe labour shortages. Unemployment stood at 2.9% in February 2020. At the start of the pandemic, unemployment increased. It peaked however in the summer (4.6% in August) and have come down since, to a current level of 3.6%.

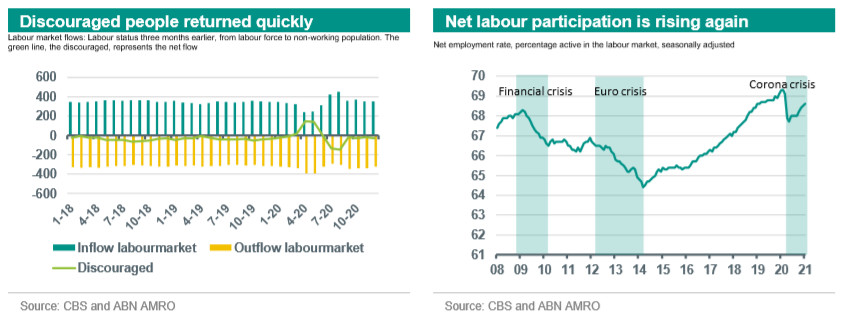

The limited increase in unemployment during the corona crisis is largely due to the government support package. It is estimated that 28% of companies with more than two employees made use of the wage subsidies (NOW). Thanks to this scheme, many workers have kept their jobs even though their employers have been hit hard by the corona crisis. The reason why unemployment has fallen in recent months is more difficult to explain. There are no clear signs that workers have become discouraged and have withdrawn from the labour market because they see no job opportunities. The graphs below show that, while the number of discouraged people rose sharply in the second quarter of last year, the net number of workers entering the labour market have been positive since. The net labour force participation rate, the percentage of the population between the age of 15-75 that is active in the labour market, is still high compared to historical levels. for the drop in unemployment is probably the flexibility of the labour market. Workers who lost their jobs at the beginning of the crisis (mostly flex workers), later found work again in the relatively labour-intensive sectors benefiting from the corona crisis, such as distribution centres and delivery services.

We expect unemployment to rise to around 5.5% by the end of this year

We expect another drop in employment during the second quarter of this year, when GDP is expected to contract. Additionally, a proportion of the people that are receiving labour subsidies (NOW) are at risk of losing their jobs when the government withdraws support as lockdown measures are eased in the second half of 2021. This will inevitably lead to a further rise in unemployment. We expect the unemployment rate to go up to 5,5% at the end of 2021.

In 2022, we expected the decline in unemployment will set in, albeit very slowly as there is a lot of slack in the labour market. This is due to a number of factors. First, the number of people wanting to work more hours increased by more than 15% in the third quarter of 2020 compared to the previous quarter. First, the employees who want to work more hours will fill the extra demand for labour, before hiring will start. Secondly, when the economy can reopen in the summer, more people are likely to re-enter the labour market. Although there was a net inflow from the non-working population to the working population in 2020, this net inflow was much smaller compared to recent years. We expect the unemployment rate to fall very gradually from March 2022 onwards to 5.2% by the end of 2022.

The initial rise and then very gradual fall in unemployment has a dampening effect on contract wage developments. We expect the collective labour agreement (CLA) personnel wages to rise only by about 1.1% in 2021. We may adjust this percentage upwards, depending on how long the NOW scheme lasts. Meanwhile, we assume that incidental wage growth (everything that happens outside of the collective agreements) will contribute negatively to the total wage growth. It is also striking that most pensions and unemployment benefits will not keep up with inflation in 2021 and that the increase in unemployment will have a strong distributional effect on household incomes (benefits are lower than last earned wages). Taken all together, real disposable income will fall in 2021.

[1] We expect that the aid measures will be reversed less quickly than the coronary restrictions

[2] There are large differences between the sectors. In the NOW scheme has led to greater job retention than in other sectors.

[3] People withdrawing from the labour market