ESG Economist - How big is the impact of a Hot-House World scenario on Europe’s GDP?

Climate scenarios provide insights into the potential economic impact of transition and physical risks. The impact depends on the nature of the scenario. In addition, the characteristics of geographies and starting points play a significant role. Also, the impacts differ depending on how they are modelled. In this note, we explore two different worlds in terms of climate for Europe: Net Zero and a Hot-House World scenario.

Two different worlds in terms of climate, Net Zero and a Hot-House World scenario, lead to significantly different impacts on the European economy

When comparing a Hot-House World with a Net Zero scenario in 2 different models, the difference in GDP impact is relatively small in the short term and can be slightly positive in the Hot-House World

In the longer term, the realisation of physical risks results in a large negative impact on GDP in a Hothouse World scenario

The longer term GDP damage of the Hot-House World scenario relative to the Net Zero scenario varies significantly between the two sets of scenarios (-6% against -15%)

The impacts do not take into account adaptation, but could still be understated as they also do not include second round effects and tipping points

Impacts on Europe

The Net Zero scenario is one in which greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are reduced to net zero by 2050 in an orderly transition that starts immediately. As a result, global warming is limited and thus, physical risks remain relatively small. Transition risk is on the one hand significant because of the amount of transition taking place, and on the other hand limited due to the orderly nature of the transition in this scenario.

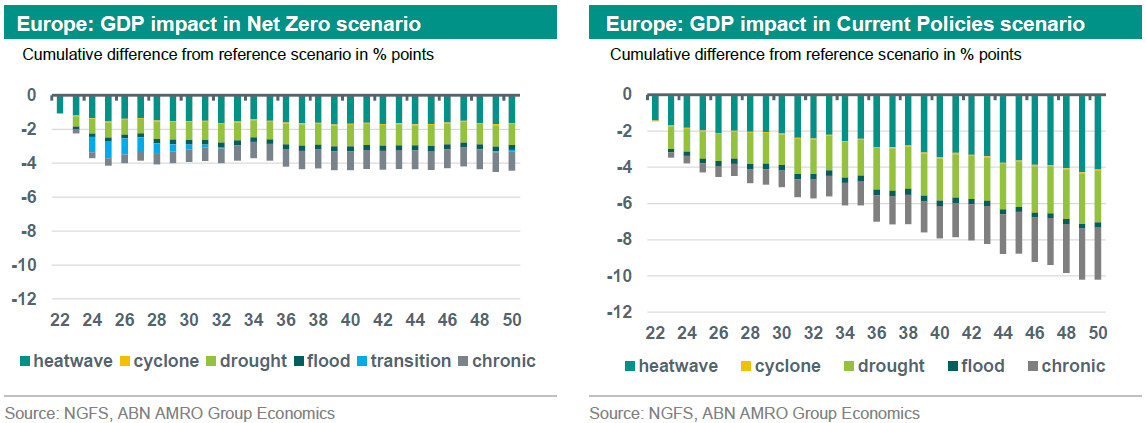

The GDP impact of these risks on Europe according to the NGFS (Network for Greening the Financial System) scenarios is shown in the charts below. When looking at the Net Zero impact in the left-hand chart, it is striking that even in this low physical risk scenario, the impact of physical risk exceeds that of transition risk in all the phases of the transition. Even in the early stages of transition, where transition costs reach their peak, transition risk is still relatively small compared to the other elements, which altogether represent total physical risk (for more notes on physical risk, please see here and here). By 2050, total GDP in Europe stands a little over 4% below the “reference scenario” that NGFS uses, which is a fictional world where there is no transition nor any climate change.

In the “Hot House World” quadrant of the NGFS categorisation, the “Current Policies” scenario can be found. This scenario, depicted in the right-hand chart above, assumes that only the policies currently in place are implemented, but no more. This leads to around 2 degrees global warming by 2050 and 2.9 degrees by the end of the century. As a result of these assumptions, transition risk is low and physical risk is high. As can be seen in the chart, this would lead to a European GDP around 10% lower than in the reference scenario. The main contributors to the decline in GDP are impacts from heatwaves, drought, and chronic impacts. In this last category falls the effect of rising average temperatures on among others labour and agricultural productivity.

Comparing the impact across 2 models

As mentioned previously, the modelled impact of a climate scenario is, among others, dependent on the way the modelling was done. To illustrate this, we have taken 2 Hot-House World scenarios that are more or less comparable in their warming assumptions for 2050: the NGFS Current Policies scenario (mentioned above) and Oxford Economics’ Subdued Climate Catastrophe/Climate Distress scenario. Both assume warming of about 2 degrees Celsius by 2050 (after 2050, the warming assumptions deviate, but for this note we only look at the period until 2050).

The results in the chart above suggest that in the short term, the GDP impact of the Hot-House World scenario could be slightly more positive than the Net Zero scenario. This is due to the fact that in the Net Zero scenario more aggressive carbon pricing drags on GDP (and increased green investment is not enough to offset this drag). This (small) negative impact from the transition costs in Net Zero - in the short term - outweighs the impact of physical (1) risk associated with the Hot-House World scenario (in which transition costs are negligible).

Over a longer time horizon (mid 2030 onwards) the negative GDP impact becomes much larger in the Hot-House World scenario than in the Net Zero scenario. This is due to the increased realisation of physical risk. The amount of damage implied in the models becomes significantly larger in the longer term in the Oxford Economics estimates than in the NGFS scenarios. By 2050, according to the NGFS, Europe’s real GDP is around 6% lower in Current Policies than in Net Zero. In Oxford’s Subdued Climate Catastrophe scenario the EU’s real GDP is 15% lower than in the Net Zero scenario. Oxford Economics does mention that the impacts constitute an upper bound, since the approach does not include any adaptation to climate change. On the other hand, it can be argued that a number of elements increasing the negative impact are not yet included: for instance, second-round effects such as mass migration, and tipping points (for instance, with permafrost thaw).

(1) Please note that, as also shown above, there is realised physical risk in the first part of the time horizon in both scenarios. But as we are looking at the difference in impact between the two scenarios here, this cancels out