US – Labour data revision may force cut

The July labour market report upended the narrative of a solid labour market. The already weak headline figure of 73k jobs gained in July was dwarfed by the substantial revisions to the May and June figures, whose estimates declined by 125k and 133k respectively. This lowered the three month moving average from around 150k to 35k. This pace is well below even recent estimates of the ‘break-even rate,’ which would keep the unemployment rate constant, and indeed, it ticked up to 4.2%. In response, Trump fired the head of the responsible statistical agency and markets quickly priced in almost a full September rate cut. We don’t think the case is that clear.

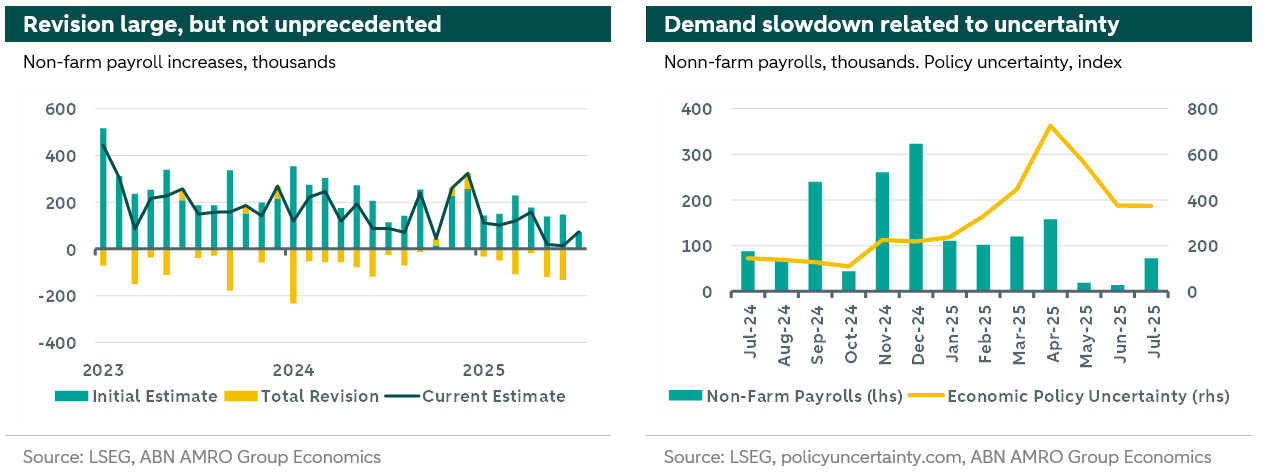

The revision to non-farm payrolls is historically large and comes at a critical moment. We’ve not seen such a big two-month revision since the pandemic, when the overall magnitude of monthly changes was much higher as well. Still, we’re currently in a period of negative revisions, and seeing the recent revision in the context of the past two years makes them seem a lot less remarkable. The BLS has generally been struggling with timely and accurate readings for a variety of reasons, including reduced survey response, volatile population growth, seasonality, and their so-called firm Birth-Death model (see an analysis on the implications for last year’s data ). This has led to larger and mostly negative revisions over the past few years. [1] The size and timing of this revision is important for two reasons. First, Fed officials remain divided on whether to cut rates in September. The new data seems to vindicate the dissenters in the latest FOMC meeting, and certainly strengthens the argument for cutting in September. The second reason is that it now shows a stark deterioration in labour market conditions that can be directly tied to the Trump administration’s policy, including timing. Indeed, looking into the sectoral composition of the revision, we see the biggest employment falls in construction and logistics, both hit hard by tariffs. These sectors initially seemed to hold up.

Hiring ground to a halt on the back of enormous policy uncertainty. As the chart above shows, non-farm payrolls declined following the peak in uncertainty. Most policy uncertainty measures, such as the US economic policy uncertainty index, as shown, or trade policy uncertainty, saw a clear peak in April and a gradual decline to still substantially elevated levels since. We’ve argued before that has more damaging effects in the short-term than the tariffs themselves. They keep firms from making decisions, because whatever may seem like a good idea with current policy, may no longer be profitable if policy changes in two months. The same goes for hiring and pricing decisions. Indeed, Q2 saw weak investment, limited pass-through in prices, and, as we now know, also saw weak hiring. It now seems generally expected and accepted that substantial tariffs are here to stay for the indefinite future. The Biden administration also did little, if anything, to reverse the Trump-I era tariffs. With that uncertainty out of the way, firms know these extra costs are here to stay and can start adjusting their business. We therefore expect investment and hiring to start to pick up again, and firms to properly start passing through these costs to their customers.

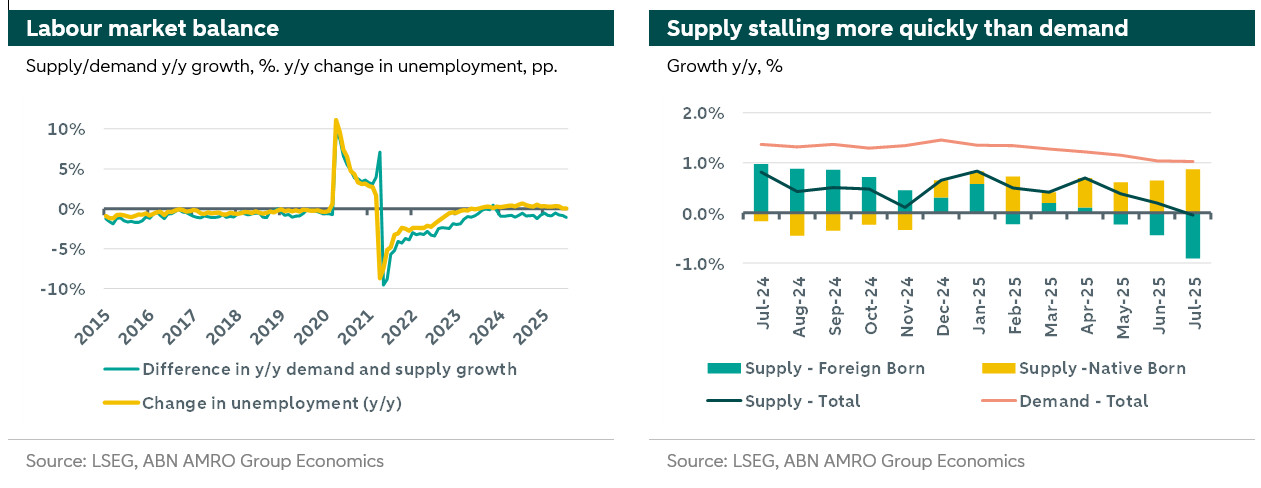

The labour market as a story of supply and demand. The strength of the labour market, and the direction of the unemployment rate, is a question of demand and supply. The left-hand chart below shows the difference in y/y growth between demand and supply and the y/y change in the unemployment rate, which line up very well. Over the past few years, demand growth – as measured by NFP growth - outpaced supply (or labour force) growth by about 0.8% per year. Still, the unemployment rate edged up marginally, which can partly be explained by people taking multiple jobs, and partly by unregistered people in the workforce. Overall, directional changes in the trajectory of the unemployment rate require directional changes in the balance between supply and demand growth.

The overall assessment that the labour market is ‘in balance’ remains valid, despite the revision. Zooming in on the last year, we see that the pace of labour demand growth is declining, but the pace of labour supply growth has decreased even more. As of July, the gap between the y/y growth rates stands at 1.1% compared to the 0.8% average highlighted above. The labour supply slowdown is predominantly driven by the Trump administration’s immigration policy. We observe slower population growth, and a decrease in the participation rate. The former is clearly directly tied to policy with both voluntary and involuntary reduction of the foreign born labour force. The latter is typically related to a fundamental slowdown, but this reduction too is more pronounced for the foreign born labour force then native born. While labour demand growth still outpaces labour supply growth, a mismatch might drive up unemployment. The decrease in supply is mostly hitting blue-collar and manual-service roles, while reduced hiring is also evident in more white-collar government and office jobs. This mismatch, which we’ve analysed in more detail , is unlikely to resolve itself quickly. It may even lead to some inflationary pressures due to labour market tightness in immigrant-dependent sectors.

This single report is not enough to drive the Fed to a September cut. The primary reason is that we get some very important data releases before the September meeting. There are two more CPI readings, an additional labour market report, and the annual benchmark to labour market data. Decreasing policy uncertainty may impact both. We’ve already seen increasing tariff-related pressures on inflation, and continue to expect that this will pick up in the coming months, with firms more willing to pass-through tariff-related costs now that they’re set to remain in place. Still, the Fed might lose its patience in waiting for inflation to rise if the labour market deteriorates further. The next report will be critical. We expect the August labour market report to show a modest recovery from the current stagnation. Moreover, the figures already released are subject to (further) revision. The historical correlation between first and second revision is near zero, so there’s an equal chance of an upward and downward revision. The Fed will likely be careful in their assessment of this data. A bad outcome for both the BLS and the Fed would be for the Fed to start easing in September with subsequent positive revisions to the labour market data. Furthermore, back in June, the median SEP forecast was for core PCE inflation to be at 3.1% and the unemployment rate to be at 4.5% by year end. Data is still largely moving in line with such forecasts, granting limited reason to put more weight on the employment mandate compared to June. A substantial downward revision on the back of the annual benchmark revision on September 9th might tip the needle though. Similar to last year, NFP has been trending up while employment has been flat or even decreasing. Last year, this played a big role in the surprise 50bps cut in September Even though the case for a September move is not clear-cut, political pressure keeps rising. Previously, the Fed tended to start easing after a number of negative NFP figures, typically in context of labour supply growth exceeding demand growth and less (or no) excess inflationary pressure. From a strict mandate view, the case is therefore less clear now, with the labour market still broadly in balance and inflationary pressure on the horizon. Different from recent episodes is the substantial political pressure coming from President Trump, who has been consistently calling for substantial rate cuts, even suggesting the policy rate should go to about 1.5%. This will not happen any time soon. Still, if inflation fails to pick up over the remainder of summer, the Fed may be forced into a cut as the wait-and-see approach becomes increasingly hard to defend. The two dissenters of the previous meeting will surely vote in favour of a rate cut. Kugler’s resignation, with Stephen Miran nominated to replace her, is likely to add a third certain vote in favour of rate cuts. The remaining voters are clearly divided in a hawkish and more dovish camp, who saw either no or two rate cuts in the remainder of this year back in June. Fedspeak since the labour report remains consistent with those two camps being present. The relative size is unclear but close to equally divided. There is therefore certainly a possibility of a precautionary cut in September. Indeed, if current market pricing persists they almost surely will. This would likely not be the start of an actual easing cycle. Rather, it would be cast as a recalibration towards neutral, positioning the Fed a bit better in terms of evolving risks to both sides of the mandate. Even then, subsequent developments remain uncertain. The Fed may shift stance again when inflation does pick up, or gradually move towards neutral if labour market pressures remain, though neutral seems pretty close to the current level. Easing to highly accommodative territory remains an unlikely outcome in the near term due to the risk of inflation expectations deanchoring. The probability of aggressive easing may increase only after Powell’s term ends and only if the economy faces a more substantial slowdown. Indeed, when both mandates are under threat, the FOMC under Powell is likely to choose price stability, but his Trump-appointed successor might be less inclined to do so.

[1] This is most strongly exemplified by the 818k reduction in NFP last year August in their annual benchmark revision. This year, the figure will be announced on September 9th, before the next Fed meeting.