US – Stacking the board: how much can Trump influence the Fed?

Perhaps emboldened by the opportunities offered by Kugler’s departure, team Trump expanded the attack on the Fed’s board. After consistent pressure on Chair Powell, they have now targeted Fed Governor Lisa Cook, exposing alleged mortgage fraud, and calling on her to step down. This would offer an additional slot for Trump to fill. With Waller and Bowman quite openly aligning with Trump’s monetary policy wishes, another governor slot would lead to four out of seven board governors blatantly supporting Trump’s wish to cut rates, and some might go further in supporting Trump’s policy wishes. The attack on Cook is the first signal that the Trump administration is casting the net wider, exploring all options to increase their influence on the Fed. Would this majority matter?

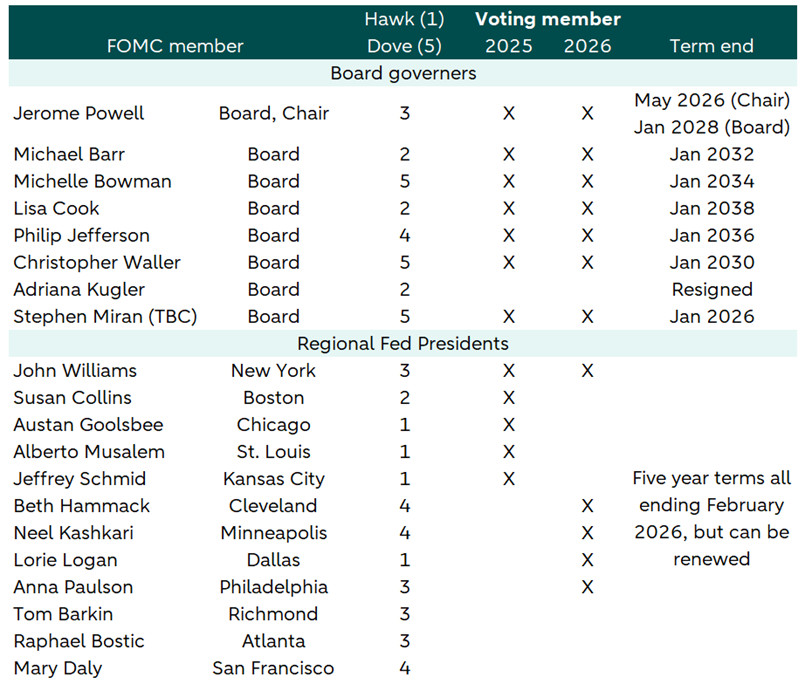

What does the voting committee at the Fed look like? In any Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting there are twelve voting members, with the Chair able to decide a draw. Seven of the voting members are on the Fed board, one is the President of the New York Fed, and the remaining four are rotated across the remaining regional Feds. President Trump has the power to nominate Fed board members, who have to be confirmed by the Senate. The regional Feds nominate their presidents, who have to be confirmed by the Fed board members. Governor terms are fourteen years, while regional fed presidents have to be reappointed every five calendar years, the next one February 2026.

A majority on the Fed board gives powers but limited monetary policy powers. The Fed board has certain powers, such as blocking the nomination or 5-year reappointment of a regional Fed president. The board members are also the ones voting on e.g. bank regulation, not the full FOMC. As for monetary policy, due to the presence of the remaining five voters, a majority on just the Fed board is unable to dictate policy. February 2026 is therefore critical. If Trump manages to get another board governor appointed by then, it is conceivable that he’d push the four Trump-aligned governors to not reappoint the more hawkish regional fed presidents, leading to an extremely dovish FOMC.

Even in the absence of any further unconventional changes, the FOMC will turn more dovish in 2026. Stephen Miran’s spot becomes available in January 2026, and Trump gets to renominate him, or someone else. It is tradition that the Fed chair gives up his board position after the Chair term ends, but it is not compulsory. Powell leaving in May would lead to another Trump nominee on the board. Powell can however stay on until January 2028 if he so chooses, which would not offer a spot. In addition, we might reasonably expect a more dovish tilt in 2026 regardless of new appointments. All nineteen FOMC officials rank differently on the hawk-dove scale, therefore erring to higher or lower policy rates. The rotation in voting members therefore changes, and the 2026 regional voters are generally regarded to be decidedly more dovish than the current voting regional fed presidents (see table below).

The dovish tilt will lead to more dovish policy in 2026. Even in the absence of Trump influence, the current economic conditions could reasonably be interpreted in hawkish or dovish manner depending on how you weigh the two Fed mandates. Historically, the Fed has reacted more strongly to weakness on the employment side. The tariff-induced weakening in non-farm payrolls could be an argument to start easing. On the other hand, inflation is already increasing and projected to increase further on the back of tariffs, which would be an argument to keep rates steady or even increase them. The most recent dot plot revealed that the FOMC members are divided across these two scenarios. The presence of these three members who will always vote for easing, along with the generally more dovish character of the ‘independent’ Fed members would lead to a dovish tilt. Rates would be lowered when a reasonable argument can be construed to do so, but we do not expect even Waller and Bowman to support cutting when it is completely out of the question, and furthermore the remainder of the committee would unite against easing.

A loss of independence for the Fed will have far reaching consequences beyond just near-term policy. In the near-term, it would likely lead to more stimulative monetary policy, which is likely to push inflation and inflation expectations up. When investors lose faith in the Fed’s ability or willingness to control inflation, longer-term rates will go up. Both the US government and US consumers and firms would then still face higher borrowing costs. It would also put pressure on the dollar and it could also lead to financial market volatility. In the long-term, the US would face significant economic instability with monetary policy ill-aligned with the business cycle, easing depending on who’s in political power, rather than what’s best for the economy. Effectively, the independent Fed is the anchor of the global financial system. It’s not just the US that would lose out. The long terms of the Fed governors, which are explicitly designed to overcome political rotations, therefore also constitute a risk as a stacked board may continue to exert pressure on policy beyond the president’s term.