US - Tariffs have entered the hard data

‘Soft’ consumer and business confidence data deteriorated rapidly due to US government policy. ‘Hard’ data has held up better, partly due to frontloading effects from the tariffs. But now the negative impact is starting to show in the hard data as well.

Over the past few months, ‘soft’ data - based on sentiment surveys or anecdotes - has deteriorated rapidly. University of Michigan consumer confidence dropped to its second lowest reading ever last month. Business sentiment, as captured by the ISM and S&P PMIs, dropped less dramatically and even rose a bit this month, but is still down from the start of the year. The latest beige book of the Fed, which summarizes anecdotal information from the districts was one of the most pessimistic since the pandemic. Yet, hard data has overall still been solid, with modest inflation, relatively strong labour market figures and even final private demand growing strongly in the first quarter. The data is muddied by the different timelines of the economy’s reaction to the historically unprecedented trade shock. This makes some data look better and other data look worse, with payback expected over the coming quarters.

One of the first places one would expect Trump policy to show up is in prices. But, after high inflation readings in January and February – which can hardly be attributed to the Trump administration – most recent, post-tariff data has been mild. To understand, let’s recap the major points in the tariff timeline; China got 10% tariffs beginning February. On March 4th they got another 10% and Canada and Mexico received 25%, which was largely reversed March 7th. On April 2nd (‘Liberation day’) we got 10% universal tariffs. Things escalated further with China throughout the start of April, reaching their peak on April 10th, before reverting May 14th. Effectively, February had 10% China tariffs, raised to 20% throughout March, and since April we’ve had higher China tariffs and 10% universal tariffs on the entire world. Available data can therefore only reasonably reflect the China tariffs.

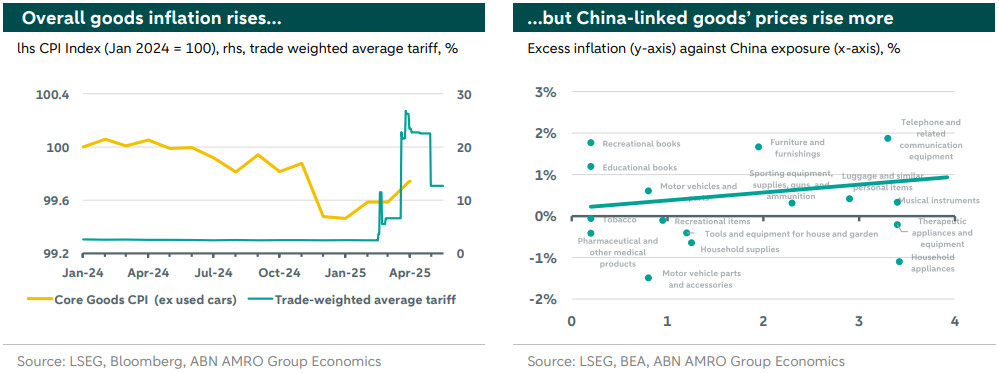

Zooming in on the core goods CPI, excluding used cars and trucks, prices rose by 0.3% since February. This is relatively high for goods inflation as most of the recent past has been characterized by goods deflation. Still, compared to an increase in the tariffs of close to 20% the figure seems mild. Is there really a link? To answer that question we dig into the China tariffs. We use input-output tables from BEA to compute a measure of China tariff exposure for the various goods in the BEA categorization, which can broadly be interpreted as the expected increase in PCE inflation of a fully passed-through 20% China tariff. We match these to ‘excess inflation’ computed as the difference between the PCE inflation over first three months of this year, minus the average first quarter inflation between 2000 and 2019. There is a lot of variability and noise in the data, but the fact that on average we see greater price increases for categories that have a higher China exposure is evidence that the elevated goods inflation is related to tariffs. The slope of the line suggests that about a quarter of the tariffs is currently reflected in prices, with great heterogeneity across goods.

It is not clear whether we should expect full pass-through, less, or perhaps even more due to second-round effects. Regardless, there is clearly still quite some ground to cover, both from the initial China tariffs, and the subsequent universal tariffs. We estimate PCE inflation will peak at 3.3% at the end of the year, up from 2.3% as of March, and likely lower in April.

Overall, we continue to expect the hard data to show more substantial negative effects over the course of the next half year. Recent data has been strengthened by frontloading effects. Upcoming months will show the payback on top off the overall deterioration. For GDP growth, a reversal of the strong imports of Q1 will mean a boost in Q2, while investment will decline. Consumption will slow, as consumers too have frontloaded purchases, and further suppressed by sentiment, increasing credit constraints, and equity volatility dampening consumption of high-income households. The de-escalation of the trade war is a positive, but current tariffs will still do substantial damage to the economy.