Dutch elections - Consensus for high deficits

The Dutch head to the ballot box on the 29th of October in an important election after a period of political turmoil. Polls signal quite some shifts, with far-right PVV as election winner once again, though it is deemed unlikely they will enter a new coalition. While still very uncertain, with centre parties, such as the CDA, winning, a more centrist government looks increasingly feasible. Party programmes share a consensus for large deficits, putting longer term public finances under pressure. Chances of a coalition with a more constructive stance towards the EU and traditionally sensitive issues, such as joint financing, have increased.

Jaap Teerhuis

Senior Fixed Income Strategist

Dutch elections; what’s at stake?

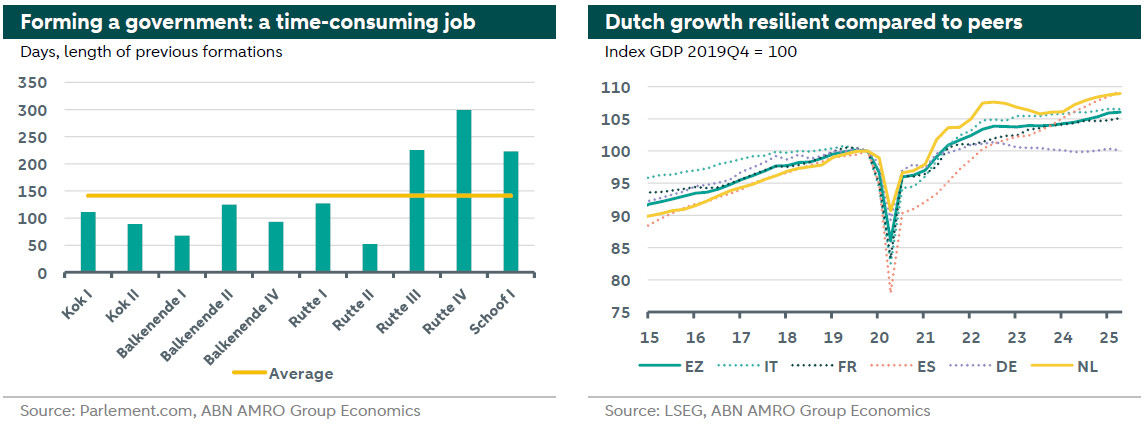

The Dutch head to the ballot box for snap elections on the 29th of October after the Schoof 1 coalition fell, having been in office for 11 months, when previous election winner the PVV (far-right) quit the coalition in June over migration. The coalition was further hampered in August when NSC (centre-right), who also won big in the election, left the already caretaker government. As a result, the BBB (right), and the VVD (liberal centre-right) are the only remaining coalition partners in the current caretaker government, leaning on just 18 seats in the polls. Political turmoil has characterized Dutch politics recently. For example, since 2020 the Dutch government had caretaker status for 40% of the time. Because of this, next to election themes such as housing and migration, stable governance has gained importance as theme this election. Possibly one reason why the CDA (Christian democratic, centre-right), who campaigns on this, has surged in the polls (see below). Heavy campaigning is expected in the following weeks until the elections, likely still leading to large changes in voting intentions like we have seen in the final weeks before previous elections.

PVV leading; CDA & GL/PvdA battling for 2nd; momentum at D66 & JA21; VVD & NSC losing out

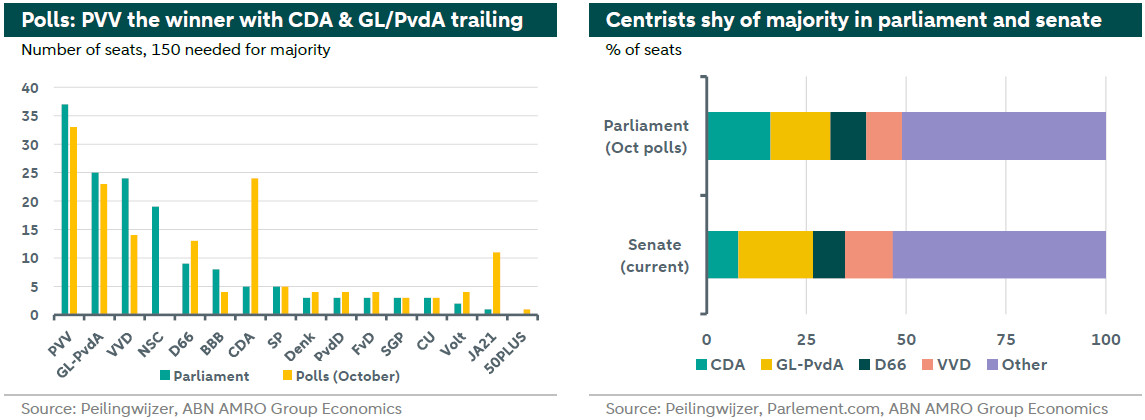

Geert Wilders’ PVV (far-right) remains the largest, currently polling at 33 seats, though losing compared to previous polls and elections. At the outset the PVV is excluded from cooperation by most centre parties, for example by former coalition partner the VVD. Much can change in the coming two weeks, and the polls did not predict the PVV's victory in the previous elections, though it is deemed unlikely that the PVV enters a new coalition. Behind the PVV, GL-PvdA (centre-left), led by former Vice President of the EU Commission Frans Timmermans, and the CDA (centre-right), led by relative newcomer Henri Bontenbal, are contending for second place although both parties are stagnating in polls recently. The momentum is visible at JA21 (right-wing), as alternative for the PVV, and more recently D66 (centre-liberal). Negative momentum is visible at NSC, gaining 20 seats in the previous elections and now polling at 0, as well as the VVD (centre-right, 10 seats lower) and to a lesser extent the BBB (minus 4 seats).

A centrist coalition looks promising, with less viable alternatives over right or left

Without the PVV, at this stage a likely coalition seems to be a broad centrist alliance, consisting of CDA, GL-PVDA, D66 and the VVD, not unlike something seen in Germany. However, all depends on the election outcome. In the current polling, such a centrist coalition will have 74 seats and lack a majority. Smaller parties could be added to reach a majority of 76 but will complicate the formation process. Secondly, it is not certain whether these parties, and specifically the VVD, which is losing in the polls, would be willing to join a centrist coalition. Given the VVD’s reluctance towards GL-PvdA, such a step would be more feasible under the CDA’s Bontenbal as Prime Minister, rather than under GL-PvdA’s Timmermans. Finally, it remains to be seen whether the exclusion of some parties of the PVV will hold in case the PVV wins by a landslide. Such a centrist coalition would lack a majority in the Senate (right graph above). Two alternative coalitions either leaning right, with the PVV and JA21, or leaning left could be considered, though less likely given the current polling. Next to these majority options, a minority government could be a non-conventional option. Based on the above, the formation process is expected to be challenging once more, despite the fact that parties expressed their readiness to form a new coalition before Christmas.

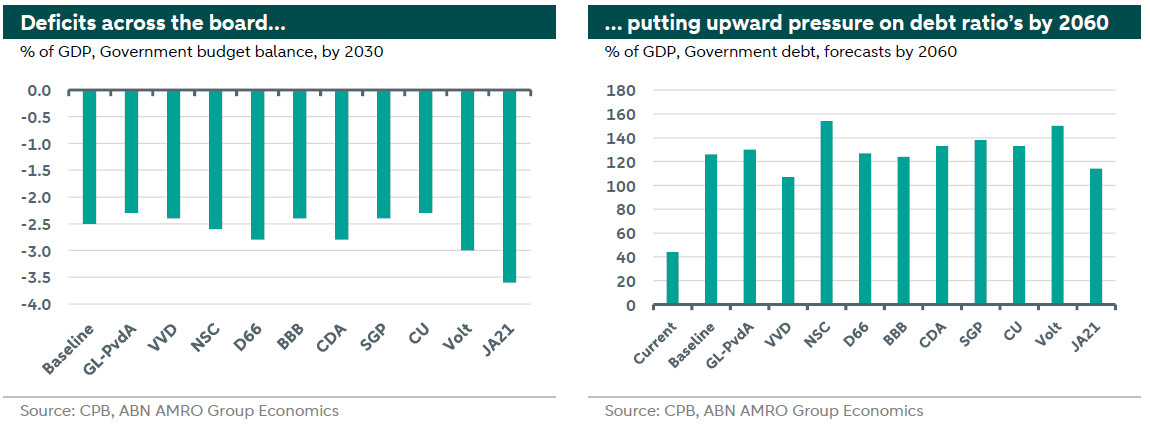

New NATO target forces parties to make choices

The current caretaker government left some big decisions for the next. The largest is the new NATO-norm of 5% of GDP defence spending, which almost all parties agree to adhere to. Next to defence, the focus points of parties range from solving the housing shortage and improving the business climate to climate change measures and healthcare. The Dutch planning bureau (CPB) traditionally carries out independent of party programmes. A few conclusions can be drawn on the basis of this. 1) Deficits remain high, in excess of 2.3% of GDP by 2030 in most party programmes, despite an increase in tax revenues. Parties differ in which taxes are increased; either business, income or wealth taxation or others. 2) Most parties, excluding GL-PvdA, choose to partly fund NATO expenses by letting healthcare spending, which due to ageing is set increase, rise less. 3) Parties take different approaches to address the housing shortage, declining business climate and climate change.

Chances of a government with a more constructive attitude towards the EU have risen

Under Schoof 1 the Netherlands had a less constructive attitude in Europe. An example is the nonconstructive stance towards the European Commission plan for ramping up defence capabilities (ReArm Europe), with parliament, including coalition partners, voting to constrain the Dutch mandate in Europe (, JA21). Judging by the programmes and the possibility of a centre coalition, the stance towards Europe is likely to turn more constructive. Parties like the CDA have also shifted on sensitive issues, such as joint financing for European public goods (defence). Additionally, on less controversial matters—such as the capital markets union and internal trade barriers—centrist parties seem to share a consensus supporting deeper European integration.

Dutch economy resilient; medium term challenges mount

The elections take place against the backdrop of a resilient Dutch economy with increasing long-term challenges. Despite various shocks in recent years, the Dutch economy has indeed shown resilience with growth outperforming the eurozone average and unemployment remaining low. In the short run, growth is expected to moderate due to weak external demand amid uncertainty and tariff impact. Constructive for the growth outlook is domestic demand, both household and government spending going up. The outlook for 2026 is more upbeat, with support from ECB rate cuts, fiscal spillovers from Germany, and further improving purchasing power. At the same time, supply-side bottlenecks, such as the electricity grid congestion, housing shortages, and the nitrogen impasse, are increasingly constraining economic growth and put downward pressure on the medium-term growth outlook alongside other challenges such as slowing productivity growth, ageing, the energy transition and climate change. As we have seen in recent years, Dutch inflation continues to exceed the eurozone aggregate, for instance due to higher wage growth and an expansive fiscal policy stance. Although the gap has gradually been narrowing, we expect Dutch inflation to continue to outpace the eurozone in the coming quarters.

Deficits across the board, with long term public finances under pressure

Deficit forecasts by the CPB show political parties’ intentions for high deficits to continue. The baseline scenario, with unchanged policies, sees the government deficit at 2.5% of GDP by 2030. All party plans see deficits in a similar range. There seems to be a broad consensus for the need for significant deficits and support for the economy, even if it is at odds with an economy running at capacity and elevated inflation (see below). These deficits forecasts exceed the target set by the influential advisory body consisting of Treasury and Central Bank officials () which advises to keep the deficit around 2%. While government finances are healthy currently, the current trajectory is one of worsening public finances on the longer term.