ECB Watch - A less independent Fed could mean more ECB cuts

The US Federal Reserve is coming under unprecedented pressure as an independent institution. As the central bank standing behind the world’s reserve currency – and the world’s biggest, most liquid bond market – this has implications that reach well beyond US shores. Our base case sees the Fed turning dovish from next year onwards, but not fully losing its independence. In that regard, whether Trump succeeds in firing board member Lisa Cook before February 2026 is the key factor to watch [1]. In this Q&A, we explore from a big picture perspective what impact the Fed’s potential loss of independence may have on the ECB, the eurozone economy and on financial markets. We consider both the spillovers from the Fed’s actions as well whether the ECB could come under similar pressure from European politicians.

The Fed is coming under unprecedented pressure as an independent institution. We assess what impact this could have on the ECB.

Financial conditions would tighten, especially via a stronger euro, which could see a second leg of the rate cut cycle

A 10% appreciation of the effective exchange rate could trigger 100bp of rate cuts all else equal, though other factors could moderate this

Financial conditions could also tighten via higher bond yields, and increased market volatility

The ECB’s institutional make up makes it unlikely that it would lose independence when it comes to its core price stability task

However, the ECB might be more susceptible to political pressure when it comes to bond market interventions to prevent fragmentation

Q1: If the Fed eases policy inappropriately, what would that mean for the ECB?

The loss of the Fed’s independence may lead it to ease policy much more aggressively than justified by macroeconomic conditions, causing inflation expectations to rise. Although rate cycles are sometimes synchronised, the ECB would not simply follow the Fed in easing policy. However, the ECB would react to changes to global economic and financial conditions that might result from overly-aggressive Fed easing. Broadly speaking, we see an ‘over-easing’ Fed as likely to drive tighter financial conditions for Europe. First, through the bond market channel: while short-end yields in the US would fall on the back of rate cuts, long-end yields would likely rise, driven by both higher inflation expectations and real . Sharply higher US yields would likely spillover and drive European bond yields higher. Interest rates on long-term lending – from mortgages to corporate bonds and SME business loans – are largely based off of government bond yields. So, to the extent that those longer term interest rates rise, this would represent a tightening of financing conditions for European households and businesses – even with the ECB keeping short-term policy rates on hold. The impact on risky assets is less clear and might vary over time. If the rise in long-term yields in the US and globally is sharp and significant, this could – together with elevated levels of uncertainty – eventually undermine risky assets. However, in the short-term, risky assets may benefit from the Fed running the economy hot.

Q2: What about the euro?

Indeed, the second major channel through which European financial conditions could tighten is through a weaker dollar/stronger euro. The dollar has already been under considerable pressure this year, partly due to the weaker US economy, but also as international investors have increasingly hedged their dollar exposures. The dollar would likely face renewed pressure under a compromised Fed. First, because concerns over US assets would intensify, and secondly, because a narrower short-term rate differential between the US and Europe would tend to drive a weaker dollar and a stronger euro. Finally US inflation expectations could also be a headwind.

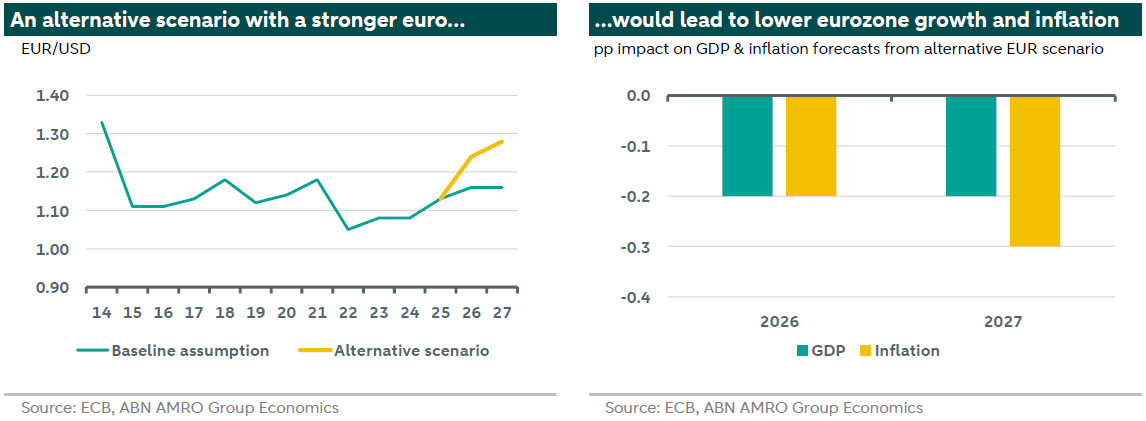

The stronger euro in turn affects ECB policy via two channels. First, it dampens inflationary pressure by making imports (especially energy) cheaper. This raises the risk of the ECB undershooting its inflation target. Second, because a stronger euro makes European exports less competitive, which would have a dampening effect on activity and employment. Indeed, in the ECB’s September macro-economic projections, staff depicted an alternative scenario with a stronger euro (around 10% appreciation from current levels) and the impact this would have on growth and inflation. The scenario implies a significant undershoot of the ECB’s target, with HICP inflation at 1.6% and the core rate at 1.5% in 2027.

Q3: What would be the trigger for the ECB to respond to these forces?

All of this could force the ECB to act, with the Governing Council potentially lowering rates in order to offset the tightening of conditions from both long-term rates and the currency. However, the magnitude and the persistence of these effects will be crucial in determining whether and by how much the ECB responds. For instance, with regards EUR/USD, Vice President de Guindos made a rare remark at the Sintra conference earlier this year that a further rise in EUR/USD would make matters ‘complicated’ for the ECB. While the Governing Council does not explicitly target the exchange rate, a rapid and sustained appreciation would lower its growth and inflation forecasts, thereby indirectly raising the chance of a policy response. Also crucial is not simply EUR/USD itself, but the trade-weighted exchange rate. If euro strength is more a matter of dollar weakness – i.e. if the euro is stable vs other currencies – the impact on growth and inflation will also be limited. All told, we judge that around a 10% appreciation in the trade-weighted exchange rate of the kind depicted in the ECB’s alternative scenario would likely be enough to trigger downward revisions to the ECB’s projections that then leads to significant rate cuts.

Q4: How low could ECB rates fall in response to excessive US rate cuts?

A scenario along the lines of the ECB’s alternative for EUR/USD, where inflation is projected to undershoot the ECB’s target in 2027, could lead to second leg of the rate cut cycle. The average of the models presented by the ECB, suggests that a 100bp rate cut would be needed to correct an undershoot of 0.3 percentage points. So all else equal, this would take the deposit rate down to 1%. However, there might be other effects at play. For instance, depending on its severity, the impact of this might also have to be weighed against possible inflationary spillover effects from the US. This could materialise if the US sees a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, and ergo much higher inflation. In addition, the ECB currently is not fully factoring in the impact of Germany’s fiscal stimulus in our view. Meanwhile, a much more negative scenario, where loss of confidence in the US dollar and US Treasurys as a global safe liquid asset, could lead to a sharp tightening of financial conditions and volatile markets that may necessitate a more aggressive response from the ECB.

Q5: What does a loss of faith in Fed independence mean for the global financial system?

The US dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and US Treasury securities are the most liquid safe asset that there is. Many key global commodities are priced in dollars, and US Treasury yields are a benchmark and anchor for interest rates around the world. A loss of confidence in either (or both) the dollar or Treasuries would therefore have profound implications for the global financial system, because there is as of yet no natural, viable alternative for either. In a benign scenario, weakness and volatility in US assets would lead to broadly higher uncertainty, lower investment and lower trade. In a worst case scenario, the erosion of these globally vital public financial goods would lead to a gumming up of the financial system and perhaps a new global financial crisis, with unpredictable effects.

The 1970s is likely a useful allegory for what might happen should the Fed’s role as a credible anchor of the global financial system be challenged. President Nixon installed Arthur Burns as Fed Chair in 1970, and proceeded to pressure the Fed into loosening monetary policy in order to drive an economic boom ahead of the 1972 presidential election. During this episode, Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, which also represented a fundamental de-anchoring for the global financial system. The period that followed was one of high financial market volatility and high inflation, which only decisively came to an end when Paul Volcker took the helm of the Fed in the 1980s and re-established a firm monetary anchor. While in some respects the global financial system is arguably more resilient than back then – for instance, financial markets are much more flexible and liberalised – in other respects, such as the dependencies that other countries have on global trade and on the stability of US assets, they are arguably more vulnerable.

Q6: Might the ECB come under the same institutional pressure as the Fed at some point?

The ECB’s narrow mandate of price stability is set out in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and revising this would therefore require an intergovernmental conference and unanimity among the 27 EU member states. As such, while some leading politicians have at various points called for changes to the ECB’s mandate, the likelihood of that actually happening appears very low, given the low appetite for revisiting the treaties. Having said that, the Treaty does not provide a precise definition of what is meant by maintaining price stability – it is the Governing Council that decides how it implements this mandate, including the choice of the price index, and how price stability is quantified. So theoretically, political interference could cause the Governing Council to re-define its mandate in a way that would allow the ECB to run easier monetary policy, without a treaty change.

However, this is just a theoretical possibility given the institutional make-up of the Governing Council. The Governing Council is made up of 26 members, of which six are Executive Board members. The Executive Board members are appointed by the European Council, acting by a qualified majority of member states. The rest of the Council is made up of the governors of the national central banks of eurozone countries, which are appointed by their respective national governments. So no one government can influence the ECB, and it would take a majority of eurozone member state governments – all with the same objective in mind – to individually appoint governors who were compliant, and by qualified majority board members that were compliant.[2] Indeed, the supranational nature of the ECB arguably makes it much harder for any one politician to influence its decisions – perhaps an example where Europe’s power dispersion works to its advantage.

Q7: What about the ECB’s interventions in bond markets? Doesn’t that make it susceptible to political pressure?

There is another domain where the ECB has been more susceptible to political pressure, and may again be in future: intervention in government bond markets in times of market stress. The ECB’s mandate of price stability does of course enable it to intervene in bond markets given that bond market crises can have major implications for inflation (as in the eurozone sovereign debt crisis). The ECB has defined the ‘singleness’ of its monetary policy (that the policy stance is transmitted smoothly across all euro area countries) as a ‘precondition for the ECB to be able to deliver on its price stability mandate’. If the ECB sees sharply rising sovereign bond spreads, that represent ‘unwarranted (and) disorderly market dynamics’, it can then activate bond purchases through its Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). The anti-fragmentation stance is officially defined as being directly related to price stability, though former ECB President Mario Draghi made it clear in his famous words that ‘within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro’.

The ECB must therefore walk a fine line when faced with these situations between doing everything in its power to meet its inflation target, and avoiding fiscal dominance. While for a country to be eligible for the TPI, it must be compliant with the EU’s fiscal framework, in practice if the stress a country is under from markets is high enough, it may feel the pressure to intervene. This might either come through altering the criteria of the TPI, or launching a new programme. The ECB might be faced with similar such dilemmas in future, particularly with regards to France. While no one country can directly influence ECB policy in this regard, other eurozone member states may also feel pressure to support an ECB response given that a sovereign debt crisis in France would negatively impact other eurozone countries.

[1] note

[2] A further layer of protection comes from the length (8 years) and staggering of Executive Board memberships. While a board member could theoretically be removed for ‘serious misconduct’ (equivalent to the ‘for cause’ that is now being used in the attempted removal of Lisa Cook from the Fed board), only the European Court of Justice has the authority to remove a board member.