ESG Economist - CBAM impacts and opportunities

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is integral to the EU Green Deal, designed to level the playing field for domestic and foreign producers while minimizing carbon leakage. The European Commission's Omnibus proposal offers simplifications to ease administrative burdens, ensuring most emissions remain covered.

CBAM would induce redistributive impacts within the EU where Central and Eastern European countries could incorporate losses

China, Türkiye, India, UK and Russia would be most affected as these countries export significant amounts of CBAM-covered products

CBAM could be perceived as protectionist, but challenging it before the WTO would be hard

It could impose undue costs on trading partners, especially least developed countries, holding back the progress of these countries

The EU can use CBAM proceeds to aid affected nations by facilitating technology transfers, offering climate subsidies, or supported loans

Introduction

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is an environmental policy initiative introduced by the European Union (EU) aimed at reducing carbon emissions and preventing carbon leakage. Carbon leakage occurs when industries relocate to countries with less stringent climate policies, undermining global efforts to combat climate change. CBAM is designed to level the playing field for EU industries that are subject to the EU's rigorous carbon pricing system under the Emissions Trading System (ETS). CBAM is part of the EU Green Deal. It entails a levy on the carbon content of imported goods entering the EU. This ensures that foreign producers exporting to the EU face similar costs for carbon emissions as EU producers. CBAM further encourages the switch to low carbon production processes in the exporting countries. The European commission opted for a gradual phase-in process for CBAM with a monitoring and reporting phase that started in October 2023, while full implementation is scheduled for the beginning of 2026. During the reporting phase, importers of commodities covered by the EU-ETS, and at risk of carbon leakage*, have to calculate and report the carbon content of their imports following complex calculations and data collection. The reporting process turned out to have high administrative burden, especially for small and medium size enterprises (SMEs). Accordingly, within its omnibus proposal, the European commission introduced simplifications to CBAM reporting obligations to reduce administrative burdens while maintaining environmental objectives.

*CBAM basically covers iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminium, hydrogen, and electricity sectors.

In this note we dive into the prospects of CBAM and the potential macroeconomic and transition impacts, while shedding the light on most affected countries and main considerations surrounding the implementation of CBAM and the omnibus proposal.

Macroeconomic implications of CBAM

CBAM combines environmental and trade aspects to address climate change and maintain fair market competition. Environmentally, it imposes a carbon price on imports, encouraging cleaner production and contributing to emission reduction globally. From a trade perspective, CBAM ensures a level playing field by imposing similar carbon costs on both EU and non-EU producers, preventing carbon leakage and protecting EU industries. Furthermore, this mechanism influences international trade dynamics by encouraging alignment with EU standards, fostering global cooperation on climate action. However, the current design of CBAM targets only imports to European markets, which will help restore competitiveness in these markets, but it does not really impact the international competitiveness of EU exports, which could be at a disadvantage because of higher carbon prices domestically. As such, CBAM will alter cost structures and trade flows with EU trading partners which have less stringent climate policies. In that regard, CBAM differs from pure traditional tariff in that exporters to the EU could avoid it if the countries adopted similar carbon pricing to that in the EU or if the exporter uses cleaner production process.

Like any trade policy, there are winners and losers to CBAM. In a DNB study on the macroeconomic implications of CBAM (), the authors identified several redistributive effects within the European Union. In particular, the analysis showed that while many member states would see an improvement in their competitiveness in domestic markets, some Central and Eastern European countries incorporated losses, on a sectoral level, from the replacement of free allowances with CBAM. Those are, for example, power generators in eastern Europe with a high share of conventional power in the electricity mix.

The impact on economic growth will also depend on how industries react to the changes in competition and cost structures. It may also differ between regions and sectors where some sectors could benefit from lower competition, while others could be hit by higher costs or retaliatory measures. The European commission estimated that the implementation of CBAM would reduce GDP by 0.22% by 2030, compared with a scenario of continued free allowances. In addition, investment is expected to witness an increase of 0.39%, while consumption will decrease by 0.56%. Accordingly, the study found that CBAM sectors, except for cement, are anticipated to witness an increase in employment and a reduction in carbon leakage, especially for fertilizers. Meanwhile, there will be substantial sectoral consequences, where European imports are estimated to decline by 4% for Aluminum, 12% for iron and steel, 15% for cement, and 26% for fertilizers. CABM would also induce some inflationary pressures as the additional costs of imports increase production costs, which in turn translate into higher costs for consumers.

Countries most affected by CBAM

The aim of CBAM is to level the playing field and competitiveness in EU domestic markets for emission intensive sectors that are most exposed to carbon leakage risk. Accordingly, the proposed design and scope covers cement, aluminum, iron and steel, fertilizers, hydrogen, and electricity ( ). Therefore, countries most affected by the implementation of CBAM are those exporting these categories to the EU. However, the impact will also depend on the stringency of climate policy in these countries, where the closer the carbon price to that of the EU, the lower the impact of CBAM on these countries would be.

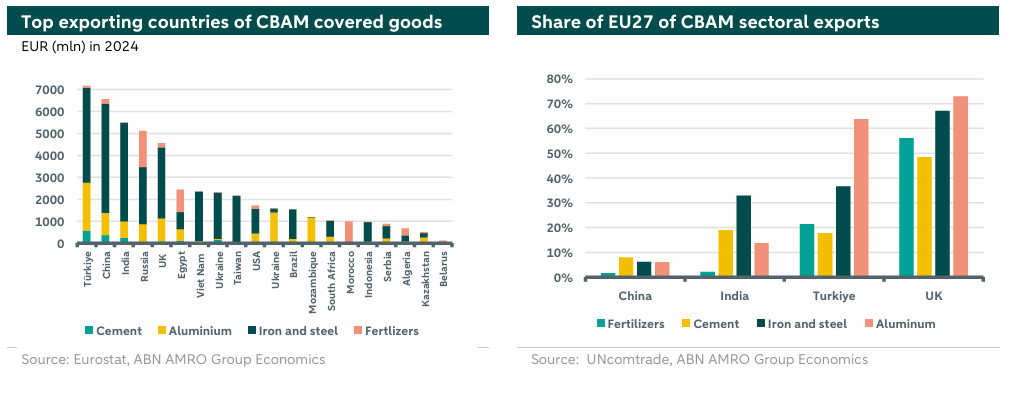

The left chart below illustrates the EU27 import value of the covered sectors (except for electricity) with major trading partners for each. The charts shows that Türkiye, China, and India export substantial amounts of steel and aluminum to the EU. Similarly, the UK and Russia position themselves as important exporters for Iron and steel, aluminum, and fertilizers to the EU.

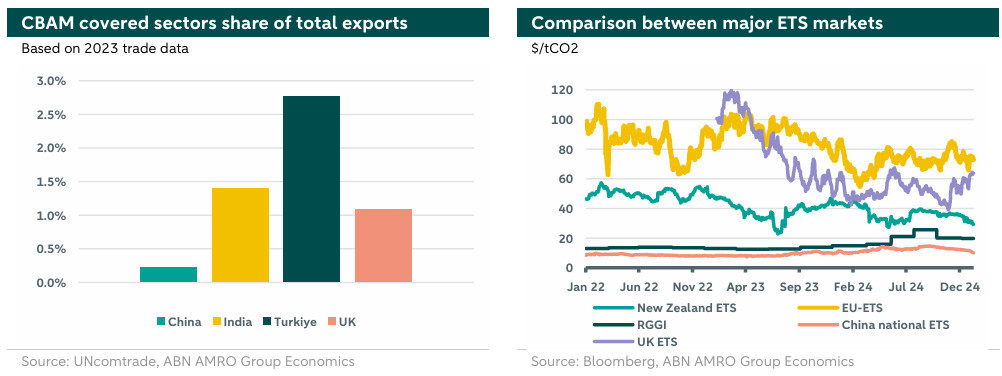

In order to better understand the impacts on top EU trading partners, we need to examine the importance of the CBAM-covered sectors in terms of their exports. Thus, we show in the chart above on the right the share of EU27 of CBAM sectoral exports, along with the EU27 CBAM sectoral share of total exports on the left chart below.

The charts illustrate that the EU27 represent a major trading partner for the UK in all CBAM covered sectors where around 70% of UK exports of aluminum, iron and steel go to the EU, while the shares for cement and fertilizers are also substantial at 48% and 56% respectively. Moreover, the UK exports for CBAM covered sectors count for around 1.1% of total commodity exports of the country. For Türkiye, this share climbs to 2.8%. More precisely, more than 60% of Turkish aluminum exports go to the EU, while European imports hold around 37% and 33% of Turkish and Indian exports for iron and steel respectively. Similar to Türkiye and the UK, Indian exports of CBAM covered sectors represent a substantial share of its total exports at 1.4%. This is not the case for China, where even though China is one of the largest EU trading partners in CBAM covered sectors in absolute terms, the share of Chinese exports of these goods to the EU represents only 0.2% of total Chinese exports.

Based on the figures above, the exports sectors of Türkiye and India are most vulnerable CBAM because of the relatively high carbon intensity of their production processes, the underdevelopment of their climate policies, and their relatively high share of their CBAM exports to the EU.

The UK has its own emission trading system of which the price difference EU-ETS is relatively smaller than with other countries, as can be seen in the right chart above. This place the UK in a relatively better position in the face of CBAM compared to other trading partners. There are also calls for linking the UK and EU emission trading systems, which would eliminate the CBAM on imports from UK altogether.

China has also its own emission trading system, but the price is still much lower than that of EU ETS, and CBAM will affect Chinese exports adversely, but the macroeconomic impact would be limited given the relatively low share of Chinese exports of CBAM covered goods to the EU in comparison to the total Chinese exports.

CBAM and the energy transition of trading partners

The EU-ETS is the EU’s flagship transition policy providing incentives to invest in clean technologies. CBAM can be considered as a complemented policy that increases the efficiency of EU ETS. However, the impacts CBAM go beyond the transition in the European Union as it targets exports of third countries towards EU markets. In that regard, CBAM helps the transition in other countries by providing an incentive for trade partners to clean up their production processes, adopt cleaner technologies, boost innovation in green technologies, and strengthen their climate policies.

However, the extent of such a transition will depend on the specificities of different trading partners. For example, the switch to cleaner production processes will be particularly hard for the least developed countries with limited resources or access to clean technologies. CBAM would limit the access to European markets and hold back the progress in these countries. At the same time, there are arguments that CBAM would impose undue costs on trading partners, especially least developed countries where such additional costs could hamper their development and their transition.

CBAM has also been criticized because it focuses on carbon pricing and does not consider other decarbonization policies. Additionally, CBAM hits developing countries with carbon intensive processes relatively more. This is the case for Mozambique and Zimbabwe, for example. Those countries need the help of the EU to clean up their processes and develop their carbon policies.

In that regard, the EU could help these countries in their transition by using the proceeds of CBAM in facilitating technological transfers, boosting industrial decarbonization, providing climate subsidies, or supported loans.

CBAM considerations

CBAM should also be considered within the current geopolitical environment, where countries prioritize national agendas while globalization loses support. Moreover, the ongoing trade war makes countries sensitive to any adjustments in trade policies. Accordingly, there are concerns that the implementation of CBAM could be perceived as protectionist or as a tool for climate diplomacy, which could intensify trade tensions and may trigger retaliatory measures and more fragmentation in international trade.

In that regard, we argue that CBAM can be motivated under Article 20 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which provides exceptions to the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules for measures that are necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health, or relate to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources. Accordingly, challenging CBAM before the WTO would be a lengthy process, where countries need to show that the EU is using CBAM to favor its own industry, which would be hard to establish given that CBAM rate is directly linked to EU-ETS price applied to domestic producers. Alternatively, some countries could opt for a trade war with Europe by increasing tariffs on European imports. We think that major European trading partners on CBAM-covered goods would be reluctant to initiate such war, given the weak position of such move at the WTO and the repercussions of a retaliation by the EU which could make the war costs far exceed any benefits.

At the same time, some countries exporting to the EU may enter in negotiations with the EU to mitigate its impacts by entering into agreements on carbon pricing or emission reductions. In that direction, countries with similar carbon pricing and climate ambitions may form alliances or regional blocks focused on climate action.

There also critics that as the current design of CBAM only covers exports to the EU. Thus, CBAM could trigger a redirection of cleaner products towards the EU and carbon intensive products to other countries leaving little change in global emissions, at least in the medium term. This highlights the role that the EU needs to play to lead clean industrial policies beyond its borders by providing support (in terms of finance or technology) to boost industrial decarbonization with its trading partners. This could be part of the EU climate diplomacy and foreign investment strategy. In that regard, the EU should also consider mitigating the impacts of CBAM on the least developed countries by using its revenues to fund policy and technological support.

CBAM in the Omnibus proposal

The Omnibus proposal aims at enhancing the regulatory framework within the EU by simplifying and streamline the reporting process under different sustainability tools such as Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF), the Emission Trading System (ETS) and CBAM. You can read more about the Omnibus proposal in our previous note here.

With regards to CBAM, the Omnibus proposal proposes a new mass threshold that exempts small importers of CBAM goods, while maintaining 99% of embodied emissions still covered under CBAM. This aims to reduce the administrative burden for small importers without jeopardizing the achievement of environmental goals. In addition, the Omnibus proposal allows for larger importers to delegate reporting tasks to third parties. It also suggests changes to the calculation of embodied emissions, financial adjustments, and allows for deductions of carbon prices paid in third countries. Default carbon prices determined by the Commission can be used if actual carbon prices are not obtainable.

The proposal argues that the proposed simplifications will allow for future expansion of the CBAM scope, along with enhancing the commission ability to process and exchange data with national authorities. CBAM declarations are done on an annual basis, specifying the quantities and emissions of imported goods. The regulation determines penalties for non-compliance and specifies the role of competent authorities in the control and implementation of CBAM.

With a focus on practicalities, starting from February 2027 the sale of CBAM certificates will be possible by member states on a common platform. CBAM will get into force for 2026 emissions, where CBAM declarants have to surrender CBAM certificates by August 31 in 2027 via CBAM registry for embodied emissions of 2026. There is also a quarterly certificate requirement by which declarants have to make sure that the CBAM certificates in their account meet at least 50% of embodied emissions from the beginning of the calendar year. Furthermore, certificates are year-specific and cannot be rolled over across the years. That is, on October 1st each year the commission will cancel all certificates purchased in the previous year that remain in the accounts of declarants.

The potential reduction of administrative costs under Omnibus proposal can mitigate some of the macroeconomic impacts mentioned above by lowering operational costs for businesses, which could lead to better trade conditions and economic outcomes. Furthermore, the simplifications could lead to less disruptive impacts for small importers, together with easing potential trade tensions with trading partners by demonstrating the EU commitment to fair implementation, which could encourage negotiations or collaborations with affected countries. At the same time, these simplifications could create opportunities for loopholes which undermine CBAM’s environmental and competitiveness objectives, along with the watering down of CBAM's ability to accurately track and reduce carbon emissions, potentially compromising its effectiveness in combating carbon leakage.

Conclusion

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is integral to the EU Green Deal, designed to level the playing field for domestic and foreign producers while minimizing carbon leakage. The phased implementation, starting with reporting in 2023 and full adoption by 2026, aims to achieve environmental goals but poses administrative challenges, particularly for SMEs. The European Commission's Omnibus proposal offers simplifications to ease these burdens, ensuring most emissions remain covered. CBAM's hybrid nature as both an environmental and trade policy impacts global competitiveness and trade flows, with countries like Türkiye and India facing significant effects due to their carbon-intensive production. While CBAM could reduce EU GDP slightly by 2030, it is expected to boost investment and employment in certain sectors. Concerns persist about its impact on developing nations and potential for geopolitical tensions, yet CBAM holds promise for fostering international climate collaboration and cleaner industrial policies beyond EU borders.