ESG Economist - Higher material costs for clean tech put pressure on the transition

In the transition to a climate-neutral economy, the need for low-carbon technologies will increase further, which will also increase demand for the metals that are essential for manufacturing these technologies. It therefore remains important to continue to monitor trends in this area in order to gain a clear picture of the opportunities and risks. The energy transition is putting increasing pressure on many metal markets. Increasingly, quantities of metals such as copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium will be needed in the coming years. In some cases, this will lead to shortages, but in most cases, supply will be more than sufficient to meet demand. In this analysis, we highlight a number of dominant critical or strategic metals that are necessary and, above all, indispensable in the energy transition. We distinguish between ‘required’ transition metals (the truly indispensable metals) and the ‘relevant’ transition metals (slightly less indispensable). We show which metals are particularly important for the production of four main clean technologies and calculate the impact of the trend in metal prices on the material costs for producing these clean technologies. Finally, we look at how demand for these metals is expected to develop in the coming years in various IEA scenarios and what influence could the supply-demand balance of these metals have on the price trend for energy transition metals. We end this analysis with a conclusion.

Many metals such as copper and nickel, but also so-called ‘minor metals’ such as lithium and cobalt, are essential for low-carbon technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, geothermal energy, and batteries

In 2025, the index of required transition metals rose by 24%, mainly due to price increases in cobalt, lithium, chromium, and copper

On balance, material costs for energy storage rose the most, by 42% in 2025

The material costs for solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal energy increased also, but to a lesser extent, by 25%, 21%, and 12% respectively in 2025

Shortages of critical metals such as copper and graphite could further drive up the price increases of primary transition raw materials, potentially delaying the energy transition

Transition metals price trends

The energy transition is metal-intensive. Base metals—such as aluminum, copper, nickel, and zinc, but also steel—are widely used and processed in low-carbon technologies. Examples include solar panels, wind turbines, geothermal systems, and energy storage techniques. However, so-called ‘minor metals’ – such as rare earth metals, lithium, cobalt, vanadium, molybdenum, and manganese – also play an essential role in the production process of low-carbon technologies.

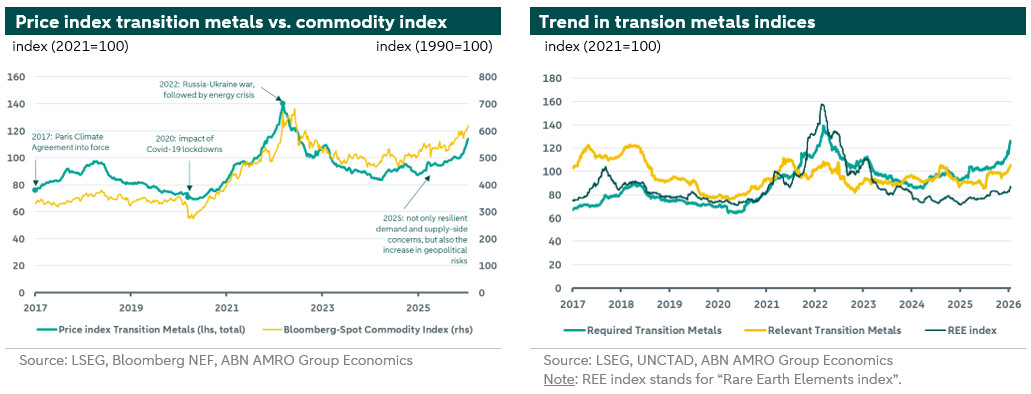

Geopolitical uncertainty is often a driver of price volatility in many commodities. We saw this not only in 2025, but it will also be a driving force in 2026. Examples include shocks in global trade (with the US as the initiator with its adjustments to trade tariffs), China's unique monopolistic position in many commodity markets, and rising global conflicts and tensions (Venezuela, Greenland, China-Taiwan, Ukraine, and the Middle East, such as Iran and Israel). This exposes the vulnerability of global supply chains to a large extent. Commodity prices usually react strongly to these trends. This is also partly reflected in the trends in the transition commodities price index and the general commodities index, see the figure on the left below.

UNCTAD has defined three categories of metals based on their relevance to the energy transition. The first category consists of 27 metals. These are the ‘required’ ones for the transition. They include cobalt, copper, lithium, and four rare earth metals (out of a total of 17 rare earth metals). The second category consists of ten metals that are ‘relevant’ to the transition, such as iron ore and steel, palladium, platinum and zirconium. The last category consists of 23 other critical metals, such as gold, silver, lead and tungsten. These metals are much less relevant to the energy transition, but remain of strategic importance. The first two categories are shown in the figure above on the right. For the third category, the data was too limited to show a representative price trend. According to UNCTAD, this distinction helps to indicate which metals are increasingly attracting geopolitical and economic attention due to their strategic importance for clean energy technologies.

In 2025, the index of required transition metals increased by 24%, while the index of relevant transition metals increased by 15%. The REE index – composed of 21 metals in total – rose by 16%. In 2026, the momentum remained unchanged and the index of required transition metals rose further by approximately 9% in January. The other two indices increased by approximately 4% during January 2026.

The stronger increase in the index of required transition metals is mainly due to very strong price increases in 2025 for cobalt (+116%), lithium (+66%), chromium (+38%), and copper (+38%). The price of cobalt rose sharply due to export restrictions imposed in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which led to shortages in the market. The lithium market also faced supply constraints during 2025. This was partly due to a sharp reduction in stocks and the closure of a large lithium mine in China. The chromium and copper markets both experienced continued strong demand, combined with some supply disruptions. The copper market was also strongly influenced by the trend in the dollar, more positive sentiment and economic data on the Chinese economy, and geopolitical tensions that further encouraged stockpiling.

Material costs implications

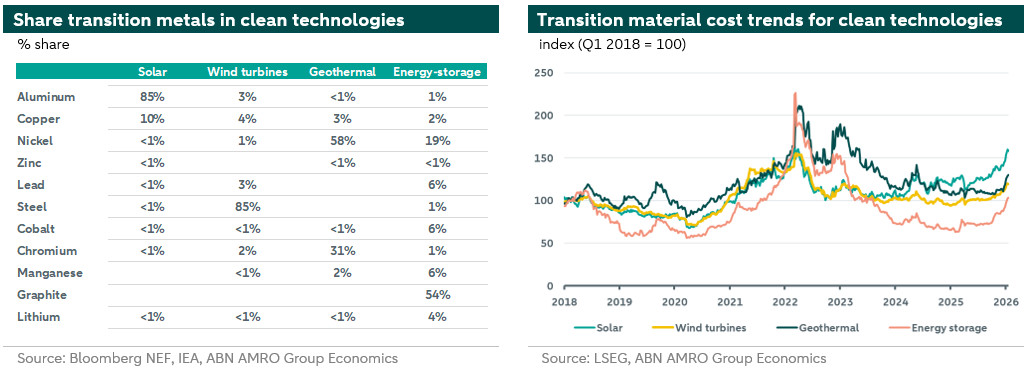

Decarbonizing the global economy will require the massive deployment of clean technologies in the coming years. Wind turbines and solar panels provide renewable energy. Geothermal energy provides a constant, low-carbon source of energy for heating buildings and greenhouses, as well as for generating electricity. Batteries will also be needed to replace the use of fossil fuels in vehicles and to support the electricity grid when using intermittent renewable energy sources. These clean technologies require all kinds of metals, with some technologies requiring a greater mix of metals than others. The table below shows this mix. Energy storage requires a much larger mix of metals than other clean technologies. The table also shows that copper is one of the most important metals in the clean tech sector. Nickel and aluminum also remain important metals, but the proportions are slightly different here. Moreover, aluminum, like steel, is mainly used on a large scale for the exterior of many clean energy technologies, rather than for the technology itself.

When we combine the metals required for each low-carbon technology in a separate raw material cost index per technology, it is particularly striking that the material costs of all clean technologies in our analysis have increased since the beginning of 2025. These material costs rise sharply, especially at the end of 2025. This is mainly due to the very sharp price increases of some metals in 2025, as we mentioned before.

On balance, these price trends mean that material costs for energy storage rose the most, by 42% in 2025. Material costs for solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal energy have increased to a lesser extent, by 25%, 21%, and 12% respectively in 2025. Although the total material costs for manufacturing low-carbon technologies fell sharply since their respective peaks in 2022, recent sharp price increases have now pushed them to above pre-coronavirus levels. In addition, material costs for solar panels have reached the peak level seen in 2022.

Supply and demand prospects

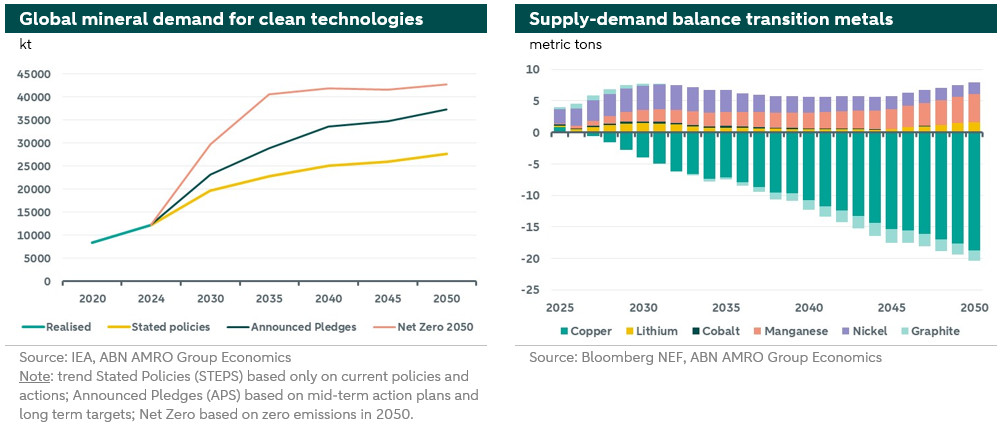

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has compiled three forward-looking scenarios that reflect the growth in demand for metals and minerals up to 2050. These scenarios are: the Net Zero Scenario, the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), and the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS). Net Zero outlines a path to achieving net zero CO2 emissions by 2050. The APS assumes that governments will fully and timely deliver on all climate-related pledges they have announced. The STEPS is the more conservative scenario and indicates the direction of emission reductions, based on current policy proposals.

The figure on the left below shows that whichever path or scenario is ultimately taken, demand for metals and minerals will increase. Growth in demand for metals and minerals will be strongest up to 2030. Growth in the Net Zero scenario will be by far the strongest until 2030, because this scenario will focus strongly on the use of clean technologies. This is much more the case than in the other scenarios. As a result, demand for transition metals increases more rapidly in the Net Zero Scenario. In the medium to long term, the growth in demand then slows down. In the other scenarios, the path is more gradual.

Continuous production of clean technologies and a reliable supply of critical metals and minerals are prerequisites for a smooth energy transition. If the supply of these metals and minerals cannot keep pace with the growth in demand, this will create bottlenecks in the supply chain. This imbalance will ultimately drive up the price of many metals and minerals, increasing concerns about the affordability of the energy transition. But there could also arise a more positive flip side. If the price of primary transition raw materials rises more sharply, this will encourage further upscaling of recycling capacity and material efficiency.

The figure on the right below shows that the copper shortage will continue to increase in the coming years. Shortages are also expected in graphite from 2033 onwards. Graphite is particularly important for the battery sector. These shortages are based on Bloomberg NEF's (BNEF) Economic Transition Scenario (ETS). This is BNEF's baseline scenario, which is based on purely competitive economies and existing short-term policy measures. In the copper market, if no new mines and recycling facilities are developed, mining capacity will be ultimately not sufficient to service total consumption. This will then lead to market disruptions and an imbalance in supply and demand. The shortages of refined copper are expected to increase more rapidly in the coming years, increasing the likelihood that the price of copper will remain relatively high. This will ensure that the input costs for producing low-carbon technologies will also remain high and may even increase further. In this scenario, there will be a greater chance that it will ultimately slow down the production of clean technologies, which could lead to delays in the transition.

According to BNEF's projections, graphite will experience shortages after 2033, as demand for batteries by then will grow faster than primary supply. For the other metals in the chart above, the markets are mainly facing a surplus. In the case of nickel and cobalt, these surpluses are the highest, averaging more than 65% of demand until 2030. Surpluses of lithium will also remain relatively high in the coming years, averaging around 45% of demand in the years leading up to 2030. Surpluses of manganese also appear high in the figure, but these are less than 10% of demand towards 2030. Such surpluses mean that the likelihood of sharp price increases for these metals in the coming years will be relatively low. However, because price trends in commodity markets have been subject to all kinds of uncontrollable influences in recent years, including non-market-related developments, sudden sharp price increases cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

This analysis shows that the energy transition is not only a technological and policy challenge, but is also increasingly becoming a raw materials issue. While the material costs of low-carbon technologies have temporarily fallen after peaking in 2022, recent price increases for many transition metals and expected shortages of crucial metals such as copper and graphite underscore how vulnerable the transition is to disruptions in this global supply chain due to increasing geopolitical risks. Regardless of the IEA scenario chosen, demand for metals and minerals will continue to grow strongly, creating the risk that scarcity and high prices could potentially slow down the rollout of clean technologies. At the same time, this presents a paradoxical opportunity: sustained pressure on primary raw materials could accelerate innovation in recycling, material savings, and alternative technologies. The central question is therefore not whether the energy transition will continue, but whether it can be supported in a timely manner by a robust, resilient, and sustainable raw materials system that fulfills its ambitions rather than limiting them.