Global Monthly - The growing stagflation risk

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has led us to make major downgrades to our growth forecasts, but also upgrades to our inflation forecasts. This is raising the stakes for central bank policymaking. Despite recent positive signs of a ceasefire, we continue to expect the conflict to trigger a lasting global trade re-alignment. We update our three scenarios outlining how we expect this to play out.

Co-authors: Hans van Cleef and Nora Neuteboom

Also this month, we look at the viability of the EU’s plan to reduce dependence on Russian energy

Regional updates: We describe in more detail our forecast revisions for the eurozone, Netherlands, the UK and the US resulting from the fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

We also preview the French presidential election, where polls are pointing to a Macron win

In China, the pandemic is driving new widespread lockdowns, adding to bottlenecks risks

Full publication in pdf:

Global View: The Russia-Ukraine conflict is raising inflation, but significantly dampening growth

It has been a wild ride for financial markets since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February, with equity markets initially plunging, and expectations for interest rate rises being pared back. Equities have since recovered significantly from their lows, while expectations for tighter policy are now even greater than they were before the conflict broke out – particularly for the US Fed, and to a lesser degree the ECB. This reflects the significant but varied effects the conflict is having on the macro outlook, and the high degree of uncertainty over how these effects work their way through economies.

The primary impact of the conflict is to push inflation (even) higher. This raises the stakes for central banks, because while there is a pressing need to get ahead of the inflation problem, policy also needs to balance this need against the rising risk of recession in advanced economies. This has been underscored by the recent plunge in consumer confidence measures across regions. However, the risk balance differs significantly between the eurozone and the UK on the one hand – where the growth hit could potentially be much larger – and the US on the other, where inflation is the significantly more pressing problem. Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic are caught between a rock and a hard place, with a growing risk of stagflation. However, the Fed is still likely to raise interest rates much more aggressively than the ECB, with the Bank of England likely somewhere in the middle.

Peace talks are likely no game changer for the macro outlook, even if they succeed

We have made significant changes to our macro outlook following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February. As we had already indicated in early March, we now expect sanctions to lead to a lasting global trade re-alignment, with dependence on Russian energy and other commodities gradually reduced, and replaced with alternative sources. Although there has been progress in recent negotiations for a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine, we do not view this as a reason to change our view. Even in the most optimistic de-escalation scenario, we cannot foresee a rapid return to the global trade environment that existed prior to the invasion. One reason for this is the withdrawal of western oil and gas companies from Russia. This is likely to cause a brain drain in technical expertise which will hit future Russian energy supplies. Another reason is that it is highly unlikely the conditions for removing sanctions (which have not been specified) would be met even in a de-escalation scenario. The question, then, becomes how long this global trade re-alignment takes, and how disruptive for economies it will be.

New base case: Energy and commodity supply shock lasting one year

Our new base case assumes, alongside the significant price shocks we are seeing in energy markets, that physical supply disruptions to key commodities are likely to worsen over the coming months as embargoes and self-sanctioning moves come into effect. This will have knock-on effects on supply chains, and there continues to be the potential for retaliatory moves by the Russian government (it remains unclear, for instance, how European energy companies will respond to demands for payments in Russian roubles). Energy prices (including electricity) are likely to remain elevated, alongside metals and agricultural commodities, with goods inflation therefore expected to spike further. Price spikes will induce self-rationing of supplies, leading to industry disruptions.

This is coming alongside existing supply side bottlenecks, which are also likely to be worsened by the recent re-imposition of lockdowns in many parts of China amid the Omicron wave. Meanwhile, the hit to household purchasing power from the surge in energy bills is already weighing heavily on consumer confidence. All of this will ultimately hit growth. While financial conditions (mainly equity markets) have bounced back significantly off their lows, broadly tighter conditions will also weigh on confidence and activity. Note, we do not assume a complete cut-off in Russian oil and gas supplies to Europe in our base case scenario – this is something we reserve for a more negative scenario outlined below. In our new base case, we assume a period of very elevated prices and supply disruptions will last around one year, as new sources of non-Russian commodity supplies are secured and global trade flows re-adjust. However, even once supply disruptions ease, prices are likely to remain elevated thereafter, and this will continue to weigh on economic activity.

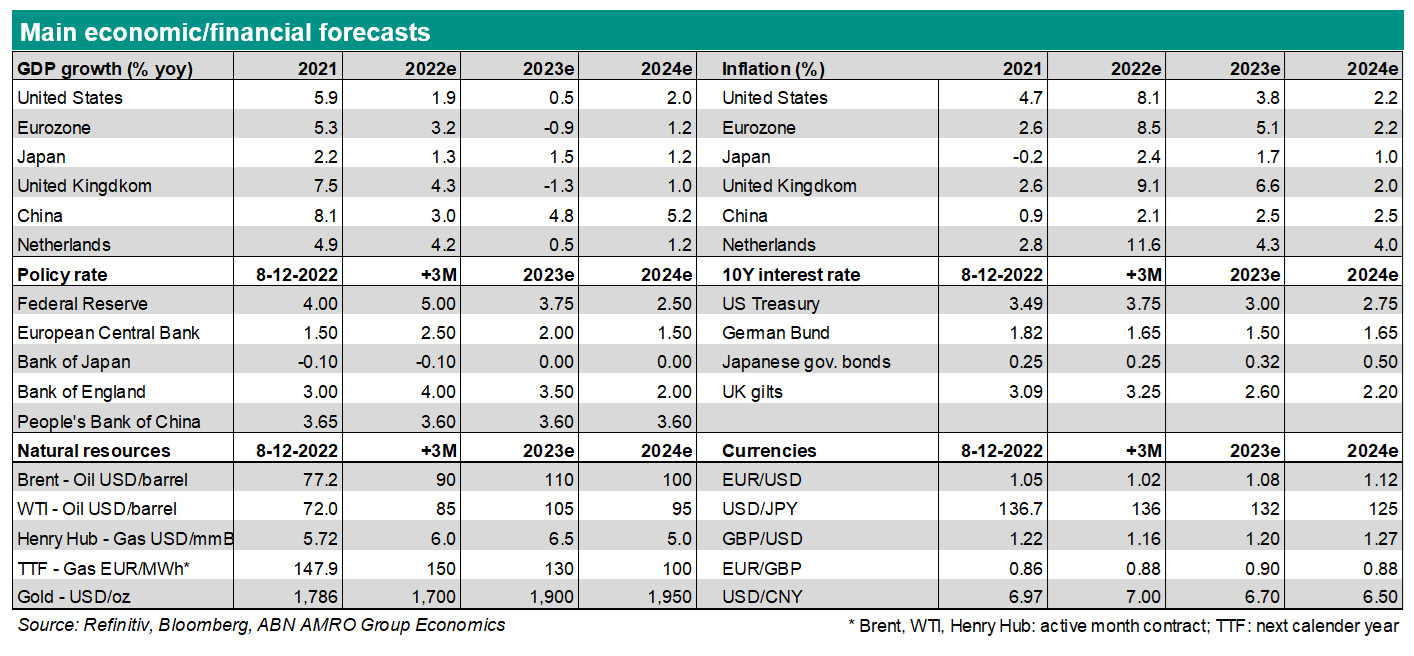

We have made sizeable downgrades to our growth forecasts for both European and US economies – we see growth being hit by a cumulative c.0.8pp over 2022-23 (see table below). While European economies are much more vulnerable to the effects of the conflict, due to their unique dependence on Russian gas, government support measures will to some extent dampen the growth impact in Europe. Another factor cushioning eurozone growth is the upward revision to growth in H2 2021, which adds c.0.2pp to 2022 growth. Were it not for these factors, we would have made an even bigger downgrade to our eurozone growth forecasts. Moreover, the downside risks for the eurozone and UK stemming from potential physical supply disruptions continue to be much bigger than for the US. On inflation, we have made even bigger upgrades to our forecasts, with eurozone inflation now expected to average 5.3% in 2022 (3.6% previously), and US inflation 6.9% (5.0%).

Governments in the eurozone and UK have already stepped in to stem the macro-economic fallout, eg. through price caps or compensation (tax cuts) to households and industry, and this is preventing a more severe hit to growth than we would otherwise have forecast. For instance, just today Spain announced a EUR16bn (1.3% of GDP) plan to cushion the blow to households. However, governments will struggle to offset the inevitable disruptions to physical supplies of commodities and components. For instance, some car producers had to pause production in early March, due to a lack of cabling supplies from Ukraine. We expect these types of disruptions to intensify over the coming months. Indeed, order lead times have already started rising again according to the latest PMIs, and this drove a renewed rise in our bottlenecks index in March. All told, we expect the eurozone and UK economies to avoid technical recessions, as even in this new environment there is still room for recovery in the services sector after the pandemic, as was evident in the recent PMIs. However, growth will be significantly lower than we previously thought.

Meanwhile, high inflation significantly limits what monetary policy can do to offset the hit to growth. While a delay to ECB tightening initially looked more likely, commentary from Governing Council members continues to suggest an appetite to begin normalising policy. As such, we continue to expect asset purchases to end by Q3, and for lift-off to start this December with a 10bp hike. For the Fed, given the significantly bigger inflation problem the US is facing, the calculus has shifted even more in favour of rate hikes. As such, following the 25bp rate hike in March, we now expect the Fed to raise rates by 50bp at the May and June meetings, and subsequently at more gradual 25bp steps until the fed funds rate reaches 2.5-2.75% in early 2023. This represents an additional drag on growth in the US, alongside the hit to real incomes from higher inflation.

Negative scenario – Supply disruptions last up to two years

In this scenario, we assume an abrupt, complete shut-off of Russian oil, gas and other commodities to Europe, with disruptions to supplies taking much longer to resolve – perhaps up to two years. The impact of a gas cut-off would be particularly negative, due to its reliance on physical (pipeline) infrastructure, and the lack of LNG terminal capacity to replace Russian supply in the near term. However, it will also be challenging to source other commodities from elsewhere at short notice, especially given the challenges in global shipping, which will be put under even more pressure in this scenario. In addition, we would expect a renewed tightening of financial conditions, chiefly on the back of equity market falls. The negative macro-economic effects will therefore be amplified, with more widespread and persistent industry stoppages, and explicit government rationing of energy supplies to prioritise households and critical industries. This scenario would lead to even higher inflation, and trigger technical recessions in the eurozone and UK economies. The US would see a bigger growth hit of 2-3pp as it would be hit harder by the knock-on supply chain disruptions in this scenario, while price spikes would weigh heavily on consumer confidence and consumption.

While governments will likely implement further support measures to cushion the blow in this scenario, central banks would continue to be constrained by high inflation in their ability to provide support to the economy. The ECB could resume asset purchases if spreads on peripheral eurozone sovereign debt widen significantly, but for the US, we would only expect some modest slowing in the pace of rate hikes, given the risks around inflation and the more modest hit to growth.

Positive scenario – More rapid and/or smoother trade re-alignment; disruptions lasting 6 months

This scenario assumes either a quicker realignment of global trade flows, or a smoother re-alignment whereby in a de-escalation, the pressure to quickly reduce dependence on Russian energy is somewhat less. However, even in this more positive scenario, we would not expect European governments to row back on these commitments, or to unwind sanctions. Nonetheless, this more benign scenario could shorten the disruption to energy and other supplies to around 6 months. The US and perhaps some OPEC countries could raise oil output in order to fill the gap left by Russia, and/or Russian oil is bought by eg. China, freeing non-Russian supply to go to Europe. The same could apply to other commodities. This would depend crucially on sufficient shipping capacity being available. In this scenario, negative macro effects are less pronounced, with only limited industry stoppages. Growth would quickly rebound once supply disruptions ease. However, inflation would remain elevated on the back of continued high commodity and goods prices. (Bill Diviney, Aline Schuilling, Hans van Cleef, Arjen van Dijkhuizen)

We summarise in the below table the various macro implications of each scenario.