Global Monthly - When will inflation get back to 2%?

Central banks are well on their way to restoring price stability, with inflation rates roughly halving from their peaks over the past year. Inflation is likely to be back near 2% over the coming year or so. However, we think the next stage of disinflation will not be as pain-free as the initial stage, and the normalisation in services inflation is likely to be slower and bumpier than the disinflation so far. A fall in services inflation will likely also require weaker labour markets and a rise in unemployment.

Global View: A rise in unemployment will likely be needed to get inflation sustainably back to 2%

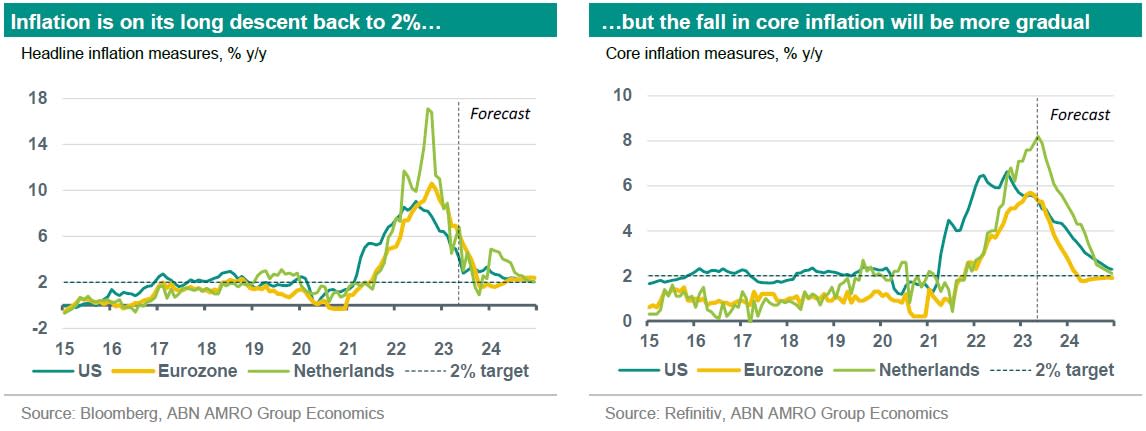

We have come a long way from the great inflation scare of 2021-22. Inflation peaked in the US last June, at 9.1%, and in the eurozone at 10.6% in October. Since then, inflation has plummeted almost as fast as it surged, by some 5 percentage points in the US and by a similar magnitude in the eurozone. The rapid pace of disinflation – which has so far occurred without a calamitous downturn – gives cause for optimism that a so-called ‘immaculate disinflation’ (inflation returning to 2% without significant economic harm) may be possible after all. While we do not expect a deep economic downturn, we do think that the disinflation still to come will not be as painless as the initial phase. When it comes to headline inflation, we think central banks may hit (or get close to) their 2% targets relatively soon – within the next six months for eurozone, and within a year for the US. But as data from the UK reminded us this week, the decline in core – particularly services – inflation is likely to be slower and subject to greater uncertainty, given that this will also depend on a cooling in the labour market. Indeed, we continue to think that more weakness in the economy, and a rise in unemployment rates, will be necessary to bring inflation sustainably back to 2% targets. And where excess demand proves to be more stubbornly resilient, such as in the UK or here in the Netherlands, we see inflation holding more persistently above central bank targets.

Disinflation so far: An energy and goods story

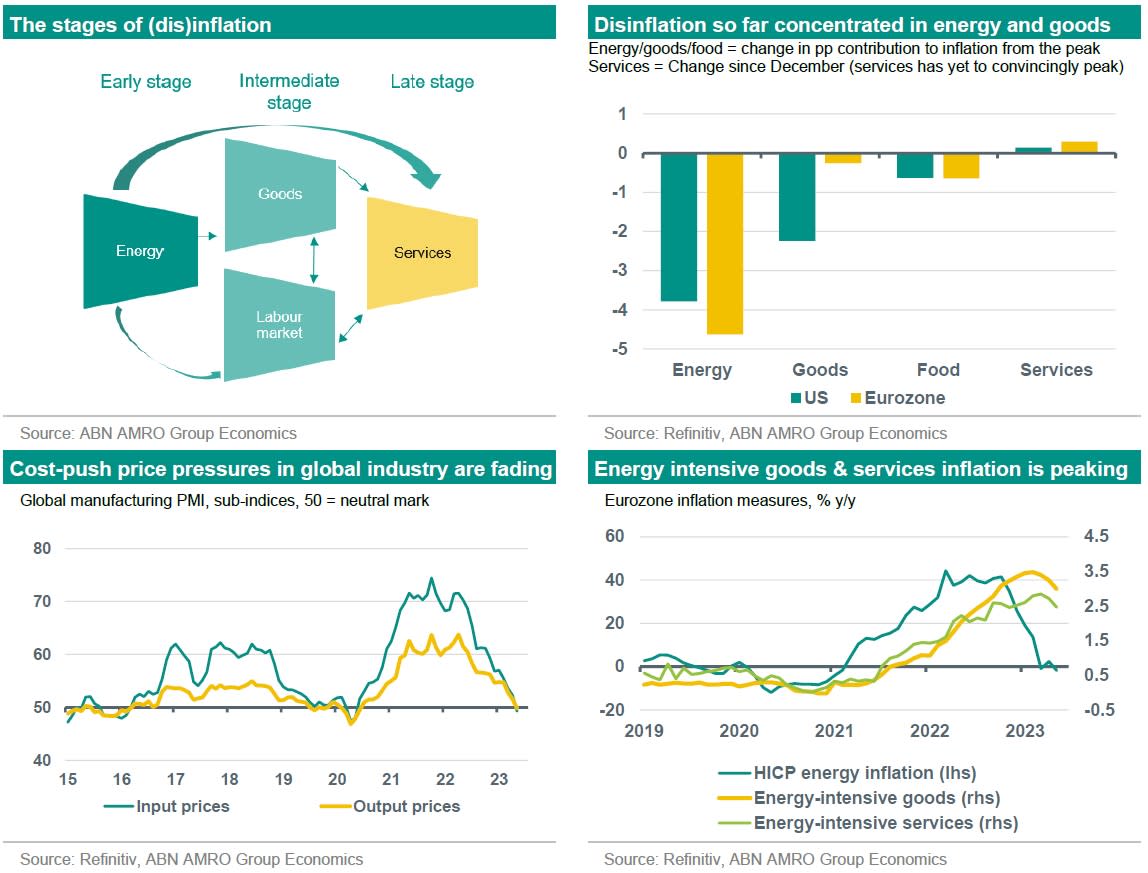

So far, the fall in inflation has been driven by the same factors that led to the initial surge: energy and goods. Falling oil prices have been a persistent drag on inflation since last June, and in the US, energy has been making an outright negative contribution since the turn of the year. In the eurozone, the energy disinflation came much later because of the unique contribution from the energy crisis, which the US was largely unaffected by, but here too energy inflation has been on a steep decline since late last year, and is now just starting to make a negative contribution.

The second stage of the disinflation – in goods – is now fairly advanced in the US and is just picking up steam in the eurozone. In the US, goods inflation had been driven largely by (used) cars, which have since seen price declines as supply chains have normalised. In the eurozone, goods inflation has been driven by pass-through from the jump in natural gas and electricity prices, and this category is now starting to see inflation declines reflecting the collapse in energy prices. More broadly, the normalisation in global supply bottlenecks is helping to lower imported goods inflation – for instance by a collapse in freight costs and a much-improved supply/demand balance in manufacturing. Food price inflation is also finally easing, reflecting the lagged pass-through from lower wholesale prices (which peaked at the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war), though in the eurozone, more energy/labour-intensive processed food inflation remains somewhat elevated.

Where inflation remains a challenge: Labour market and services

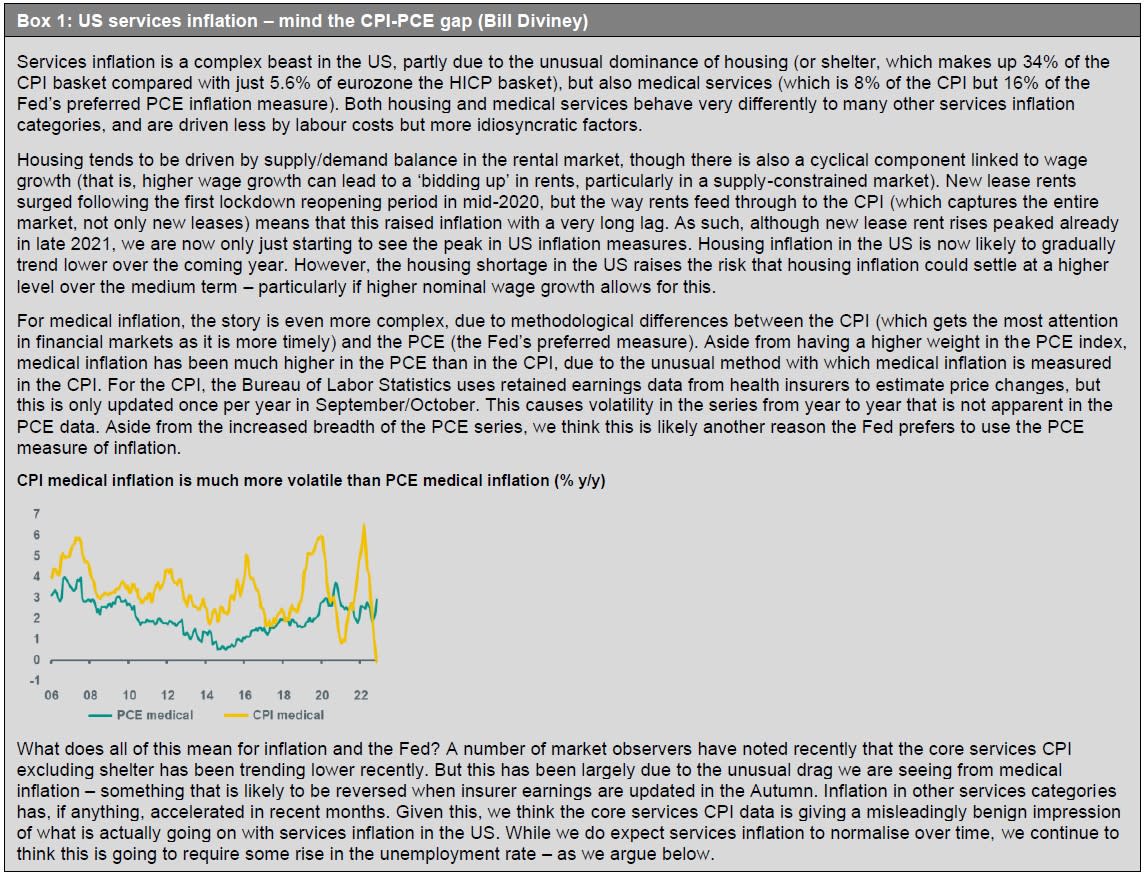

As is often noted by central bankers, tight labour markets have so far not been much of a driver of inflation. But this says nothing of the future. Just as energy and goods disinflation trends intensify, we now see the labour market becoming a more significant driver of inflation, mainly in the services sector. This is important, because unlike volatile energy and goods inflation, services inflation tends to move much more slowly and so is more likely to persist. Services inflation encompasses a broad mix of categories, and – particularly in the US – it is driven by many factors other than just the labour market (see Box 1). But broadly speaking, the longer-term driver of most categories of services inflation is unit labour cost growth: that is, wage inflation adjusted for gains in productivity. And it is here where inflationary pressure is still building. Nominal wage growth is showing some signs of peaking – at least in the US and at the eurozone aggregate level (the Netherlands and the UK are notable exceptions) – likely due to a cooling off in inflation expectations as energy and goods inflation has fallen back (1). However, unit labour cost growth has accelerated, largely due to continued strong jobs growth, which has persisted despite the weakening in aggregate demand. This has led to a collapse in productivity.

How will businesses respond to the jump in unit labour costs: with layoffs or price rises?

So far at least, businesses appear to be passing on higher unit labour costs by raising prices (particularly in labour-intensive services where demand is more resilient), and in future they may accept some lowering of profit margins (see this month’s Spotlight). We think this will prove unsustainable. With interest rates expected to remain relatively high over the coming year, we expect weakness in aggregate demand to persist, and for this to ultimately drive a rise in layoffs and in the unemployment rate. This should lead to a recovery in productivity, and – given that this will also ease some of the labour market tightness we have seen – this should also further dampen nominal wage pressures. Taken together, we expect this to drive a fall in unit labour cost growth, and over time to lower services inflation back to more normal levels.

With that said, there is a risk that the experience of the post-pandemic period continues to make employers hesitant to let go of workers, out of the fear that it will be hard to find replacements once the economy starts to recover again, i.e. what economists refer to as labour hoarding. If unemployment fails to rise over the coming year, we think central banks may have to raise interest rates even further to dampen demand, and/or the rate cuts we currently expect to take place late this year in the eurozone and next year in the US could be delayed.

Can labour market tightness be resolved without a rise in the unemployment rate?

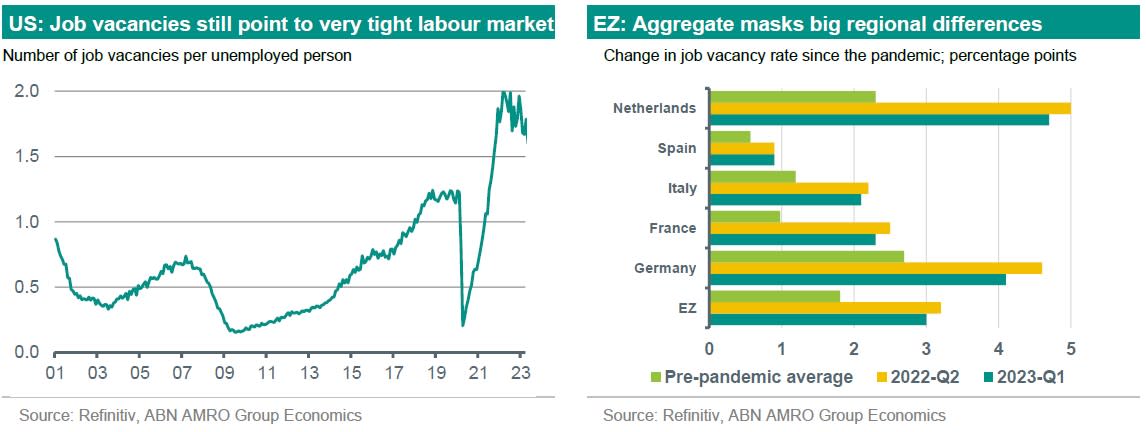

A key driver of elevated unit labour cost growth is the rise in nominal wage growth. While wage growth looks to be peaking, persistent labour market tightness in the US and parts of the eurozone could mean wage growth settles at a higher level than before the pandemic. This in turn raises medium term inflation risks. A by Olivier Blanchard and Ben Bernanke – one that is likely to prove influential among central bankers – argues that although tight labour markets were not responsible for the initial rise in inflation, they are likely to play a bigger role in inflation going forward, and that “controlling inflation will thus ultimately require achieving a better balance between labour demand and labour supply.”

One issue the Bernanke-Blanchard paper homes in on is the role of excess demand indicators such as job vacancies (and the ratio with unemployment). This, they argue, gives a better read on the labour supply/demand balance than the unemployment rate alone. To illustrate why: the US unemployment rate at present is actually fairly similar to where it was before the pandemic, but the job vacancy ratio is much higher than the pre-pandemic level, at 1.8 vacancies per unemployed person. This suggests a much tighter labour market than before the pandemic – reflecting greater excess, unfilled demand. Indeed, in previous Global Monthly publications we also used a measure of total labour demand – employment + vacancies – to help paint a more complete picture of labour supply/demand balances.

If we accept the job vacancy ratio as the best indicator of excess labour demand, this raises the question: could the labour supply/demand imbalance be resolved by a drop in job vacancies alone, rather than a rise in labour supply (which – without further rises in already high-participation, as in eg. the Netherlands – implies higher unemployment)? In the US, this has actually been the trend so far: job vacancies have fallen by more than two million over the past year, while unemployment has been remarkably stable. In the eurozone, vacancies have also declined (albeit still on the high side in the Netherlands and Germany), while the unemployment rate has fallen even further. Future developments are unlikely to be as benign. The Bernanke-Blanchard paper argues that – assuming the recent relationship between job vacancies and unemployment holds (what is known as the Beveridge Curve) – unemployment in the US will have to rise above 4.3%, from 3.7% at present, to ensure inflation falls sustainably back to 2% over the medium term. We ultimately expect weakening demand to drive rises in unemployment in both the US and the eurozone over the coming year. Unemployment has already risen in Germany by 0.6pp to 5.6% in recent months, and we expect a rises in the eurozone aggregate unemployment rate to 7.4% by late this year, up from 6.6% currently. In the US, we expect a rise to 4.8% by the end of 2024, up from 3.7% as of May.

Conclusion: Inflation peaking does not necessarily mean it will fall sustainably back to 2%

We judge that inflation has peaked in both the US and the eurozone, and that it will continue its steep downtrend over the coming months. And our base case is that inflation will fall sustainably back to the 2% targets of the Fed and ECB over the next 18 months. However, this base case hinges on a rise in the unemployment rate that corrects labour supply-demand imbalances and brings unit labour cost growth back down to more sustainable rates. Should unemployment fail to rise as we expect, we think central banks run the risk that inflation settles at a level persistently above 2% over the medium term. This could mean further interest rate rises, or a later start to rate cuts than we currently expect.

(1) Much of the rise in nominal wage growth – particularly in the eurozone – is likely attributable to the jump in energy, goods and food inflation, where tight labour markets enabled workers to bargain for wage gains that make up for their loss of purchasing power. Given this, it is likely that the fall in inflation in these categories will dampen at least some of the wage pressures.