Global Monthly - Will labour shortages prove inflationary?

Labour markets have tightened across the board, but with large differences in how much. We take a deep dive into supply and demand-side developments, and find that the US is experiencing particularly extreme labour market tightness, with the UK and the Netherlands close behind. For the eurozone in aggregate, labour market tightness is much less of a concern, keeping the prospects for a surge in wage growth low. However, the aggregate masks big country divergences.

Co-author: Nora Neuteboom

Global View: Job vacancy rates are surging – where have the workers gone?

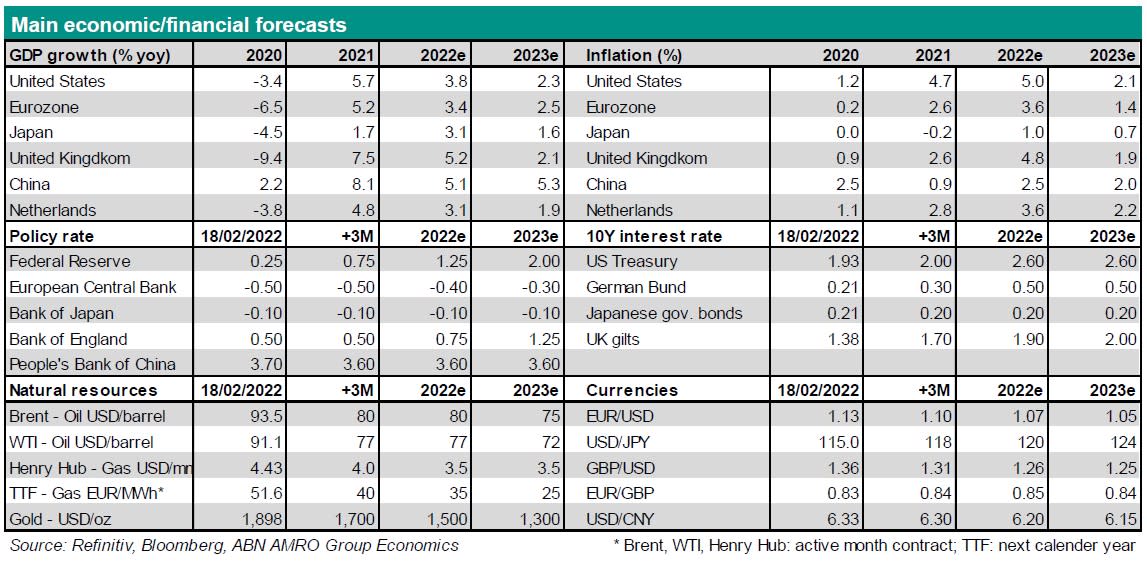

Economies are rapidly rebounding from their Omicron-induced slump, which itself proved more shallow than feared. The eurozone composite flash PMI jumped 3.5 points to a 5 month high of 55.8 in February, while in the US, high frequency indicators from pandemic-sensitive restaurant dining and air travel sectors showed activity has already erased the Omicron losses of December and January. Indeed, the most pressing concern for policymakers continues to be inflation rather than the pace of recovery, and we made further upgrades to our inflation projections across the regions, largely on persistent energy and goods inflation. We also brought forward the timing of ECB rate hikes, given the recent shift in communication from Governing Council members, although unlike in the US, we see a significant risk that growth and inflation undershoots in the eurozone end up derailing ECB rate hikes. Indeed, we have made downgrades to our eurozone growth projections on the back of tighter financial conditions and the hit to real incomes from inflation. Key to the medium term inflation outlook continues to be the labour market. With that in mind, this month’s Global View tackles the seeming shortage of workers, what this means for wage growth, and whether we should worry about a wage-price spiral taking off.

Where have the workers gone?

Will sufficient workers be willing and able to fill current and upcoming demand for labour? This is the key question to understand where inflation dynamics will go in the medium term, and what actions central banks are likely to take. In this monthly we therefore focus on these labour market dynamics, paying special attention to the US, the Eurozone, the UK and the Netherlands.

Tight, tighter, tightest

Labour markets are tight across the board, but there are large differences in just how tight. The eurozone aggregate shows that the vacancy rate has increased much less sharply than we have seen in the UK and the US. Within the eurozone, the variation in labour market tightness by country is large as well. In northern European countries like Germany and the Netherlands, vacancy rates are high and increasing rapidly, while in for example Spain and Portugal vacancy rates are low and increasing only gradually. Although the ECB considers eurozone aggregates for its policy decisions, divergence in macro- economic fundamentals within the eurozone remain a challenge.

Potentially more ‘hidden’ vacancies in the pipeline

Particularly in extremely tight labour markets, employers may be discouraged to post their vacancies if no candidate is expected to apply. This can be considered hidden demand for labour that may come forward once more workers join the market. To get some sense of whether this is what is going on, we compare the survey results of employers claiming that labour shortage is limiting production to actual vacancies posted. In the Netherlands we see that the increase in the employers mentioning worker shortages is stronger than the increase in actual vacancies posted. This signals indeed that the ‘discouraged employer effect’ may be at play. While this discouragement creates a barrier to growth in labour demand at present, the ‘hidden’ vacancies are likely to be posted once employers perceive increased chances of finding candidates. In the eurozone manufacturing industry, we do not see any sign of a discouraged employer effect yet.

Are we above pre-pandemic demand?

Is labour demand already running above pre-pandemic levels, and if so, could it cause capacity constraints that prove inflationary? We have analysed this question from two angles: the total demand for labour (employment plus vacancies), and from employer surveys in manufacturing and services separately.

Only the Netherlands is above pre-pandemic levels

The pandemic led to a destruction of jobs that was visible in a drop in vacancies and rising unemployment. However, as economies were opening up in between lockdowns, new vacancies were posted and filled. The question is: did the creation of jobs make up for the destruction of jobs since the pandemic? Or, in other words, has the total demand for labour gone back to pre-pandemic levels?

Despite the extremely tight labour market situation in the US – where wages have also risen to around 6% on a 3m/3m annualised basis, total demand for labour has still not gone back to pre-pandemic levels. This is not because vacancies haven’t risen, but because more jobs were lost during the pandemic than new ones have been created. We will get back to this when looking at the supply side of the labour market.

In the UK – another extremely tight labour market – total labour demand is even further away from pre-pandemic levels. Here too, it seems that the massive vacancy rates increase has been more about restoring lost jobs from the pandemic than about creating additional labour demand. Still, total demand remains below pre-pandemic levels, indicating that there is still more room for recovery of previously lost jobs.

The Netherlands seems to be the exception to the rule: employment and vacancies have grown to above pre-pandemic levels. Total labour demand is now at 0.8 pp above pre-pandemic levels. This is largely due to the fact that fewer jobs disappeared during the pandemic. In the second quarter of 2020, the number of people employed declined only by 166,000 and has since more than recovered. In the meantime, 317,000 additional people have since joined the working population, and despite this, vacancy rates are still increasing.

Eurozone averages hide large differences

Employers’ own assessment of whether shortages of staff constrain their productive capacity provides a more nuanced angle within the Eurozone. On aggregate, in both the industry and services sectors around 27 percent of employers consider shortage of staff the main limit to production. Again here, the Netherlands shows the most extreme situation, particularly in services, where 43 percent of employers indicate that labour shortages are their main capacity constraint. German employers also face severe capacity constraints from worker shortages, in both services and manufacturing. In Italy and Spain on the contrary, very few employers signals worker shortages as their main capacity constraint.

Where are the workers?

If total demand for work is not yet at the level before the pandemic in most countries, then it must be the supply of workers that creates tightness. Current labour supply data reveals striking differences across regions that help explain differences in wage pressures. The figure below plots the participation rates for different regions amongst people of 16 to 64 years old.

On the one extreme, there is the US where millions of workers have voluntarily left the labour market, causing participation to drop in an unprecedented way. About half of the people who dropped out of the labour force went into early retirement, and are thus unlikely to return.

Eurozone participation back to level but below trend

The Eurozone experienced a double dip in participation that followed the two large lockdown periods, but current participation rates are back to pre-pandemic levels. That said, participation is still below the pre-pandemic trend. Another factor, spotted by recent , that is currently is limiting labour supply in the eurozone is migration. Since the pandemic fewer people have migrated to the eurozone, particularly from non-eurozone EU countries, and many European workers from abroad have returned to their home countries. This has had a (likely temporary) downward impact on labour supply of about 1.5 million workers.

However, the labour supply picture in the Eurozone might still be blurred by the fact that wage subsidy schemes are keeping people in (possibly) ungainful employment, i.e. that these workers might be made redundant once subsidies come to an end. At its peak, take-up of wage subsidy schemes in Europe was as high as 16% of the labour force in 2020. With the current low level of unemployment in the euro area (7% in December) and the high percentage of employers seeing labour shortage as their main hampering production factor, the end of wage subsidies should provide some relief to the tight labour market. That said, it is highly uncertain how big the current take up still is. In Germany 2.7% of the workforce is still dependent on wage subsidies as of January 2022, while in France that figure was 2.2% as of December 2021. How many of these workers will re-enter the labour market and whether these workers match the vacancies posted is unknown. Depending on labour market rigidities per country, this frictional unemployment will eventually resolve as long as the job market remains tight.

Is long-covid reducing UK labour supply?

The UK shows a striking pattern of its own, where participation seems to be on a slow trend down since the pandemic. While one can explain differences between the eurozone and US patterns of participation from the fact the eurozone fiscal aid was directed at preserving jobs through wage subsidy schemes versus the US, where people were made redundant and then received government support via unemployment benefits, the UK had a similar wage subsidy scheme in place as the eurozone countries. A closer look at the motivation of people leaving the British labour force shows that at first, participation declined mainly due to people leaving the workforce to study. Currently, long lasting illness is has become the main reason for staying out of the labour market.

The Netherlands: participation instead of wages

While demand for labour has increased massively, wages have hardly moved, with Dutch employers resorting to recruiting workers directly from education, from flexible jobs and from the pool of discouraged workers. Over the past year, the largest increases in worker participation rates are seen amongst the younger workers (15-34 years old) and workers with a non-western migrant background. Participation levels have also increased because a declining number of people have been leaving the workforce since the pandemic. It could be that the ability to work from home has incentivised people to stay on their job a little longer.

Whether there is more potential for increases in participation depends on the ability of about 1 million workers that are marginally attached to the workforce to make the switch to employment. Even in the Netherlands, labour supply still has some hidden reserves from the wage subsidy schemes that keep people on the payroll but out of work. In November and December 2022, about 4 percent of the workforce was receiving wage subsidies via their employer. These schemes are expected to end soon. Restaurants and bars have been the main receivers of support during the 5th and hopefully last wave of infections, and with the economy reopening, the worker shortage is also largest in this sector. This is a problem that may thus solve itself as subsidy schemes end.

Conclusion: Eurozone unlikely to see wage increases that prove inflationary

There is no doubt that labour markets are tight everywhere. In the US it is the most extreme, but the UK and the Netherlands are close followers. In the Eurozone in aggregate, it is a much less pressing issue at the moment.

As such, prospects for wage growth are the highest in US, but are also high in the UK. For the Netherlands, despite the labour market being as tight as the UK’s, wage growth is less likely given that participation increases have helped to rapidly fill vacancies. Despite this additional participation, worker shortages are still a problem, and it remains to be seen how much further participation can increase before wages need to rise. We currently expect a modest 2.2% wage growth for 2022.

The US wage pressure stems from a negative supply shock that may not resolve soon, and this is creating sustained wage pressure even though labour demand has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. If the January surge in retail sales (+3.8% m/m) does not correct in the coming months, this could generate additional wage pressures, with a serious risk of a wage-price spiral.

Only in the Netherlands has total demand for labour seemingly surpassed pre-pandemic levels. In fact, despite a jump in participation, there is still growing demand for labour, with vacancy rates continuing to rise. Looking ahead, given the expected increase in workers searching for jobs as wage subsidy schemes end, we expect wage pressures to remain modest in the coming year.

In the eurozone as a whole, vacancy rates have increased at a much more modest pace, showing that tightness is less of a problem at the aggregate level. On the supply side, the end of wage subsidy schemes will release new labour supply on to the job market just as in the Netherlands. The risk of mismatches is however hard to assess. The eurozone’s labour market rigidities, both in geography and across sectors, may prove more inflationary than aggregate numbers suggest. But even if it does, we do not see a wage pressure in the eurozone aggregate that is anything like what we are seeing in the US. If wage growth accelerates significantly in say, NL and Germany but not elsewhere, this could create a dilemma for the ECB – but we are not there yet.