Japan - The Land of the Rising Yields

We expect drags from US tariffs to keep a lid on Japanese growth. Trade talks with the US are taking quite some time. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) recently lowered its inflation forecasts, but upside risks remain. We expect the BoJ to stay on a cautious, gradual hiking path. In its June meeting, the BoJ announced to slow its pace of tapering, as expected. High public debt and rising rates pose challenges, but there are risk-mitigating factors. Meanwhile, the Japanese government bond curve has steepened due to a higher term premium. We do not have indications for structural US debt outflows by Japanese investors, yet. We expect the yen to appreciate versus the US dollar in 2025-2026.

Jaap Teerhuis

Senior Fixed Income Strategist

Co-author: Sonia Renoult

Drags from US tariffs to keep a lid on Japanese growth

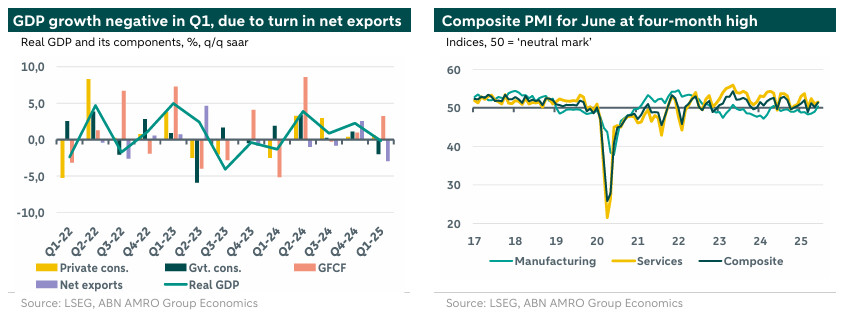

Japan’s growth outlook is shaped by external threats and domestic challenges, both cyclical and structural. Annual GDP growth fell to a post-pandemic low of 0.2% in 2024 partly reflecting spillovers from 2023, when quarterly growth was negative for three subsequent quarters. Quarterly growth picked up in in the course of 2024 on the back of firmer private consumption, whereas investment growth remained highly volatile. Sequential growth dropped back to negative territory (-0.2% q/q saar) in Q1-2025. This was mainly driven by a sharp turn in the growth contribution from net exports, despite some frontloading of exports to the US in the run-up to higher tariffs. Base effects are still expected to positively impact annual growth this year, but US tariffs will likely form a drag (see below). Following the weak Q1 GDP print, we cut our 2025 growth forecast to 0.8%, from 1.2%. This adjustment is in line with the Bank of Japan (BoJ) recently lowering its 2025 growth forecast (from 1.1% to 0.5%), although the BoJ did this before the US-China truce reached in Geneva. We expect annual growth to remain below trend in 2026 (0.7%), quite in line with consensus including the BoJ. Over the longer term, the main challenges to growth remain the ageing of the population and demographic decline, low productivity growth (particularly in the services sectors and SMEs) and labor market rigidity.

Recent monthly indicators for Q2 paint a bit of a mixed picture. Japan’s (flash) composite PMI for June rose to a four-month high of 51.4, so well above the neutral 50 mark separating expansion from contraction. Japan’s manufacturing PMI was reported at 50.4 for June, back above the 50 mark for the first time since May 2024. The manufacturing PMI’s export subcomponent has improved somewhat in May/June following the US-China truce reached in Geneva, but at 47.8 remains in contraction territory. Meanwhile, annual export growth turned negative in May, with exports to the US clearly coming down in April and May, while import growth turned even more negative. On the consumption side, retail sales growth accelerated to a three-month high of 3.5% y/y in April (in nominal terms, so more or less flat in real terms). Consumer confidence improved a bit in May, but is still at relatively low levels. All in all, we think Japan will skirt a ‘technical recession’ in Q2 (two subsequent quarters of negative quarterly GDP growth), in line with consensus.

Trade talks with the US are taking time

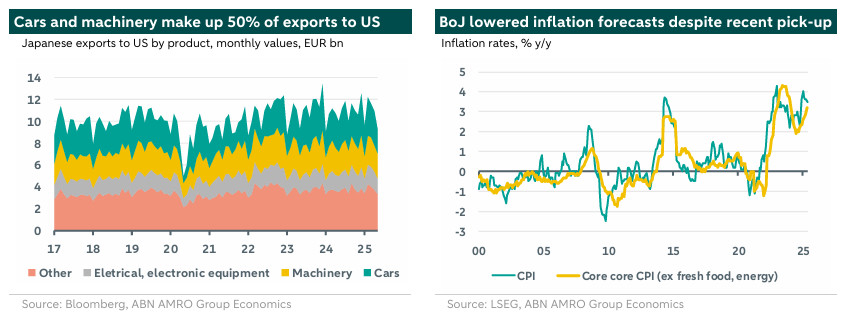

With its strong global position in the production of cars and (electronic) machinery, Japan is a clear potential victim of the ‘get industry back to the US’ MAGA approach of the 2nd Trump administration. Japan currently faces 25% tariffs on car exports to the US, which accounted for ±30% of all 2024 exports to the US, and a 50% tariff on steel and aluminum. Japan also faces a reciprocal tariff of 24% announced in early April, but this has been postponed to early July. Should the US come with more product-specific (Section 232) tariffs, that would likely also hurt Japan. Trade talks between the US and Japan are evolving, but have not led to quick results yet. There was some hope that US president Trump and Japan’s PM Ishiba would be able to sign a deal at the G7 meeting in Canada on 15-17 June, but for several reasons that proved elusive. That was not only due to distraction from the Iran-Israel escalation, or the fact that Japan toughened its stance due to elections in Tokyo (June) and the upper house (July), but also reflects underlying positions that are wide apart. The official stance of Japan is that it aims for a review of all US tariffs. Meanwhile, it looks as if the US is also aiming to include non-tariff barriers into the negotiations. For instance: in an assessment of US trading partners’ foreign exchange policy published in early May, the US Treasury stated that the Bank of Japan should continue hiking interest rates to strengthen the yen and correct US-Japan trade imbalances. Meanwhile, the recent US deals with the UK and China suggest that the ‘floor’ of 10% for reciprocal tariffs could be maintained for Japan as well. Following the G7 meeting, Ishiba emphasized that Japan would prioritise ‘national interests’ in its trade talks with the US. He added the importance of moving slowly but surely, without being rushed into a deal. The politically sensitive takeover of US Steel by Nippon Steel has recently been approved, after a lengthy negotiation process.

BoJ lowers inflation expectations on tariff impact, but upside risks to inflation remain

Although CPI (core) inflation has been ticking up again since end-2024, and Tokyo inflation data remain ‘hot’, the BoJ recently revised down its inflation forecasts for the fiscal years 2025 and 2026, to 2.2% (from 2.4%) and 1.7% (from 2.0%), respectively. That’s broadly in line with our forecasts (2.6% in calendar year 2025 and 1.8% in 2026). According to the statement, the BoJ expects the impact of rising import prices and the recent rise in food prices to fade. Core inflation is expected to come down due to a deceleration in economic growth. The BoJ is still confident that CPI inflation will settle at a level consistent with the 2% target in the second half of the projection period (so beyond 2026), as labour shortages will grow as economic growth recovers. Upward inflation risks stem from the Middle East escalation, although oil prices have fallen back sharply to pre-conflict levels recently. Japan is the world’s fifth-largest oil importer, with around 10% of oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz destined for Japan.

The BoJ will continue to look closely at wage growth. Nominal wage growth briefly came down in early 2025 (mainly driven by technical calendar effects) while picking up again in April, although remaining below the 3% pace which is consistent with the medium-term inflation target. In real terms, wage growth remains in negative territory. That said, spring wage (‘shunto’) negotiations still point to solid momentum going forward. The average wage increase in 2025 for major companies was reported at 5.4% in late May (2024: 5.6%), and the equivalent for SMEs at 4.0% (2024: 3.6%). Still, the share of companies that will participate in these wage agreements seem to have fallen somewhat, partly due to US tariff policies. Wages also have become a prominent political issue in the run-up to the July upper house election, with the ruling Liberal Democratic Party aiming for a structural 1% per annum rise in real wages.

We expect the BoJ to stay on a cautious, gradual hiking path

In spring 2024, the BoJ exited from its very accommodative monetary policy, by ending its negative-interest-rate and yield-curve control (YCC) policies while announcing a winding down of its asset-purchasing programmes – see Japan - BoJ March moves do not change our view of cautious hiking path. Since then, the BoJ stayed on a cautious hiking path, in line with our expectations. After small hikes in March and July 2024, the BoJ hiked by 25bp to 0.50% in January 2025. With growth and inflation expectation forecasts cut down due to the impact from US tariffs (as described above), the BoJ kept the policy rate unchanged in the meetings of March, May and June. Policy rate guidance by BoJ Governor Ueda was watched closely at the BoJ meeting of 17 June. Ueda gave the impression that he is willing to consider a rate hike, should there be sufficient evidence that the BoJ forecasts for growth and inflation (both lowered recently due to the tariff shock, see above) will be realised. That evidence will partly be a function of the outcome of evolving US-Japan trade talks.

We expect the BoJ’s gradual rate hike path to continue. We have penciled in one more rate hike for this year, and one for 2026. This is broadly in line with consensus (median estimates of other analysts). It is hard to be precise on the timing, but we have pushed out our expectations for the next rate hike to Q4-2025 (from Q3-25). While the 31 July meeting of the BoJ will probably be a ‘live one’ (meaning that a rate hike is not completely off the table), we deem it likely that the BoJ will remain cautious (also taking into account volatility in bond markets) and wait for more clarity on the growth and inflation trajectory after the conclusion of trade talks with the US. Financial markets seem to have interpreted Ueda’s recent comments also in a dovish way. Swap traders priced in a 65% probability of a 25bp hike by end-2025 on the day before the BoJ meeting, and this probability has fallen to 56% just after the meeting (currently 64%). The probability for a July hike being priced in has fallen to a very low 3%.

Bank of Japan slows pace of tapering, as expected

In July 2024, the BoJ presented a form of ‘quantitative tightening’ by introducing a reduction in its monthly purchases of Japanese government debt by JPY 400 billion per quarter, from JPY 5.7 trillion in August 2024 to JPY 2.9 trn in Q1-2026. The BoJ then also stated it would come with an interim assessment of its tapering schedule in June 2025. And indeed, in the 17 June meeting, the BoJ announced to slow the pace of tapering from Q2-2026 onwards, with quarterly reductions of government bond holdings by JPY 200 billion per quarter. This was broadly in line with market expectations. This shows the BoJ is determined to reduce its interference in the bond market further over time, even in a time of high volatility, in an orderly, predictable way. It also became clear that the BoJ would concentrate the reduction of its monthly bond purchases on JGBs with maturities up to 10 years, while leaving the monthly purchases of the very long end (maturities over 25 years) unchanged.

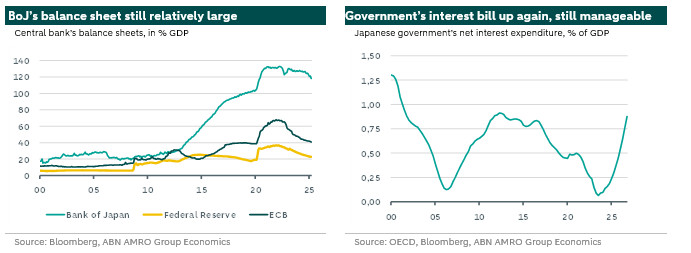

Despite the ongoing tapering programme, the BoJ’s government bond purchases and its overall holdings are still very large. The central bank’s share of the total outstanding Japanese government bonds and T-bills holdings stood at 46,3% in Q4-2024. Since the introduction of its Abenomics in 2013, when the Bank of Japan sharply stepped up its asset purchasing programmes, the BoJ’s balance sheet has grown much more sharply than those of other DM central banks, and at 118% of GDP (March 2025) is now still much larger than for instance the Fed (23%) or the ECB (41%).

High public debt and rising interest rates pose longer-term challenges, but there are risk mitigants

Longer-term challenges to Japan’s sovereign creditworthiness stem from large budget deficits and very high (gross) public debt ratios coupled with rising interest rates. Still, after a spike of the budget deficit to 9.0% of GDP in the first pandemic year (2020), the government has succeeded in reducing the budget deficit sharply, to a 32-year low of 2.2% of GDP in 2024. This has helped to stabilise the (gross) public debt ratio around 240% of GDP, although the Japanese government remains by far the most indebted worldwide by this (gross) measure. The budget deficit is expected to move up again this year, given some fiscal slippages to appease parts of the electorate and more pressure to raise defence spending. The Japanese government recently stated it will raise defence spending to 2% of GDP by 2027, up from 1%, despite pressure from the US to go even higher. Although the interest expenditure bill is expected to increase the coming years, its relative share is expected to remain manageable as a share of total revenues (around 6%) and GDP (moving up towards 1% – net). This partly relates to a relatively favourable redemption profile, with an average duration of outstanding government debt of almost 10 years. The risk of debt distress is also mitigated by the fact that Japan’s government debt is largely held by domestic entities, with a BoJ share of currently 46%. Coupled with a strong external profile (current account surpluses, Japan is large net external creditor, yen has global reserve currency status), this explains why we have not seen any changes in the ratings from Moody’s, S&P and Fitch since 2015, and all of them have a stable outlook at the moment.

JGB curve steepened due to higher term premium

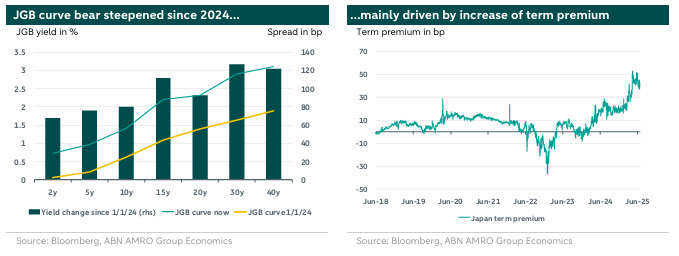

The BoJ's long-standing accommodative monetary policy has kept JGB yields low across the curve for many years. In addition, the Yield Curve Control policy, whereby the BoJ set a maximum target for 10-year JGB yields, has ensured that interest rates have remained stable for many years. Since the introduction of the YCC policy in 2016, the BoJ has made the policy more flexible on several occasions, each time widening the bandwidth within which the 10-year JGB yield could fluctuate, until it was completely abandoned.

As a result of the BoJ starting to raise its policy rate and abandoning the YCC policy, interest rates in Japan have risen significantly. This has steepened the yield curve, with 30- and 40-year JGBs underperforming in particular. The 5s30s JGB curve has steepened by around 120bp, with the steepening since the beginning of April being particularly significant (see left-hand chart below). After Liberation Day on 2 April, the 5s30s JGB curve rose by almost 50bp, after which the BoJ announced measures to counter volatility at the long end of the JGB curve, as described above.

One of the causes of the steepening of the curve is that term premium has risen. Although there is consensus in the market on the concept of term premium, there is no consensus how to measure it. Our approach to estimate the term premium involves a residual method, where we discount the market expectations of short-term rates to isolate what remains that accounts for the changes in yields. As shown in the right graph below, the term premium of the 10-year JGB has increased by more than 40bp since the start of last year, when our estimate of the term premium showed that there was no term premium incorporated in the 10-year JGB.

This development of term premium is also evident in other bond markets. In the US, term premium has experienced a significant increase due to rising concerns over fiscal policy and the lack of clarity in US government economic policy. Also in Germany, term premium has risen over the last two years as the market priced in the rise in the free float of Bunds as the ECB started to reduce its balance sheet and the German government announced a stimulus package to revive the German economy.

Japanese investor flows do not indicate structural outflows from US Treasuries – yet

Data from the Japanese Ministry of Finance (MoF) shows that Japanese investors hold large positions in government bonds from other countries. Japanese investors hold more than USD 1 trillion in US Treasuries, while their holdings in European Government Bonds (EGBs) are also significant. Given the scale of these investments, any change in the investment policy of these investors could therefore have consequences for these markets.

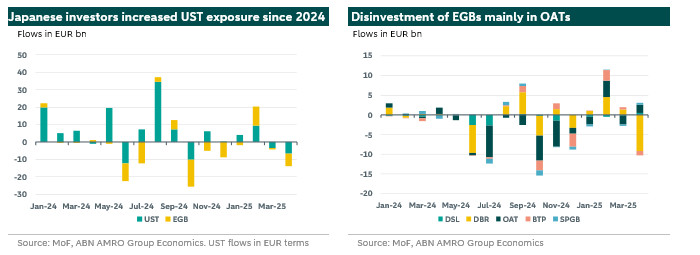

The monthly flow data published by the Bank of Japan provides an overview of the changes in positions in these markets. The left-hand chart below shows that, on balance, Japanese investors have reduced their investments in EGBs since January 2024, while their exposure to US Treasuries has increased significantly since the beginning of last year. It is also striking that within EGBs, there has been a particular divestment of French OATs and, to a lesser extent, of Italian BTPs and Spanish SPGBs which have a lower credit rating (see left-hand chart below). In relative terms, compared to the total outstanding debt, the divestment in Dutch DSLs is the largest, but its impact has not been visible in the spread development.

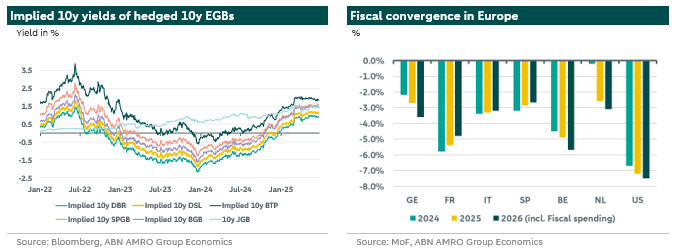

An important consideration for Japanese investors in foreign government bonds is the cost of hedging currency risk, as many Japanese investors purchase these bonds on the basis of an FX hedge. The left chart below shows the development of implied yields for various EGBs based on 6-month FX hedging costs since the beginning of 2022. This chart shows that from the beginning of 2023 until the end of last year, the implied yields of all EGBs were lower than the 10-year JGB yield, making it unattractive for Japanese investors to buy EGBs on an FX hedge basis. However, since the end of last year, FX hedging has become cheaper, which means that Italian BTPs in particular, but also French OATs, Spanish SPGBs and Belgian BGBs, currently have a higher implied yield than the 10-year JGB.

In addition to FX-hedged implied yields, credit quality and the economic outlook of the countries Japanese investors invest in are also important factors they take into account. In the US, the fiscal situation is expected to deteriorate further, especially when the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ (OBBBA) passes in the Senate, while there are concerns whether market participants will be willing to absorb the addition supply of US Treasuries that is expected. Recently, EGBs are often mentioned as an alternative to US Treasuries, but for the time being, data from the MoF does not indicate that Japanese investors are following this path. Given the size of their exposure to US Treasuries, a rotation from US Treasuries to EGBs from Japanese investors could be a problem for the Treasury market.

However, several countries in Europe are also facing challenges in keeping their public finances under control. Germany recently increased its funding requirement for this year as a result of its decision to increase defence spending and to finance the announced stimulus package. Still, Germany is able to temporarily bear a higher budget deficit as its debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low compared to many other countries. Only the Netherlands has a lower debt ratio. The debt ratio remains high for Spain and Italy in particular, although these countries have made progress in reducing their budget deficits in recent years, while the political situation in these countries is relatively calm. This does not apply to France, where the budget deficit is high and the political situation offers little hope for a quick solution to this problem (see right-hand chart above). This has probably also been the main reason why Japanese investors have reduced their exposure to OATs in the recent period.

Based on this and in combination with lower hedging costs, we expect that Japanese investors will be able to invest more in EGBs in the coming period, particularly in Italy, which on fiscal metrics is converging with core and semi-core countries, but still offers an attractive pick-up. The BTP market also offers decent liquidity which is a key factor for Japanese investors as well. Furthermore, we still expect further divestment in US Treasuries which could benefit the European debt market, with perceived better economic and policy stability.

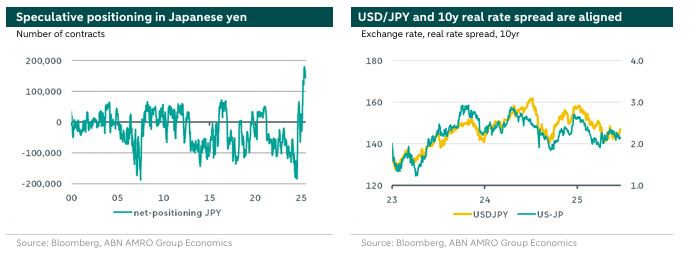

We expect the yen to appreciate versus US dollar in 2025-2026

The Japanese yen has rallied around 7.8% versus the US dollar, but has declined 3.5% versus the euro year-to-date. The rally of the yen versus the US dollar has lost momentum. The main reason for this that there were a lot of traders betting that the value of the US dollar would go down against the yen, which is reflected in having "net long" positions in yen. These positions had reached record levels (see graph below on the left), similar to when traders bet heavily against something in the past ("net short" positions).

The Japanese yen usually goes up when there's uncertainty and investors become worried, which is known as "risk-off" behaviour. However, that has not happened recently because of position overhang. When investors become cautious, they first sell their large positions to take profits such as long yen and short dollar. If the mood turns more negative and reaches panic levels, they could start buying the dollar and yen as a safe haven.

We think the Japanese yen will get stronger compared to the US dollar this year and next year. This is mostly because the US dollar is expected to become weaker. The reasons for this dollar weakness include higher risks associated with the US, the policies of the US government, the large fiscal deficit, and generally negative sentiment towards the dollar.

How the yen performs against the euro will depend on a few factors. These include the large amount of yen positions that investors currently hold, the differences between the monetary policies of Japan's central bank and the European Central Bank, and the overall risk sentiment of investors.

Original publication date 26 June 2025