Kevin Warsh’s Reverse Operation Twist

The Trump administration would like to see long-term interest going down yet oddly Warsh’s vision of the Fed appears to imply the opposite. There is a trinity of steepening policies, though in this note we focus on his policy to rein in the footprint of the central bank’s balance sheet. Shrinking the balance sheet would need the Fed to go back to a scarce reserves policy, which would make it more difficult to set interest rates. More likely is for it to reduce the skew of its Treasury holdings towards longer-term securities to market-neutral in a Reverse Operation Twist. The Fed’s Operation Twist in 2011-2012 flattened the curve and lowered the term premium and this would likely have the opposite impact. The US Treasury could alter its issuance policy, in effect conducting its own Operation Twist as part of a 2026 Fed-Treasury accord. The rising funding needs of the US government could still make these shifts challenging, meaning they are more likely to be gradual.

All aspects of Kevin Warsh’s vision for the Fed point towards higher long-term rates. This appears odd given he is the Trump administration’s nominee to be the next Fed Chair, while the Trump administration would like to see long-term interest going down. Broadly speaking, Warsh’s statements on the Fed can be summarized by a trinity of steepeners. First, he believes policy should be conviction based rather than data-driven or forecast based. This heightens the chance of extended periods of inappropriate policy, predominantly on the exceedingly easy side, pushing up long-term rates. For instance, his conviction that AI will be disinflationary because of higher productivity, does not seem to consider that the economy may boom due to AI investments before the productivity acceleration comes through. Nor that higher productivity could push up neutral rates. Second, he has pushed for less transparency, with less communication from FOMC officials. This increases policy uncertainty and hence interest rate volatility, which could translate into a higher term-premium. Third and foremost, Warsh has been a strong opponent of balance sheet operations, which have historically been tilted towards the longer-end, and therefore exerted a flattening pressure on the curve. There are a variety of ways in which the Fed may try to shrink the balance sheet, should agreement be found. In this note, we explore these paths, evaluating their likelihood and impact.

Warsh set out his agenda for the Fed in a G30 speech (see ) in April of last year. Balance sheet policy received substantial attention. He explains his view that the Fed has entered a period of ‘Central Bank Dominance,’ where the persistence of the Fed’s expanded balance sheet contributed to ‘dangerous’ US fiscal policy as well as the inflation surge of this decade. On the former, he notes that the Fed encouraged spending when times were rough, but did not call for discipline in good times. He felt QE was appropriate to further ease financial conditions beyond the zero-lower bound of the policy rate in 2008, but thought they should have been quickly reversed, going so far as to resign from his Fed role over the implementation of a second round of QE in 2010. In his view, the downward pressure on yields resulting from it allowed fiscal policymakers to spend more than they should, as they were subsidized. He calls this monetary dominance as opposed to the usual fiscal dominance. Essentially the suggestion is that the Fed’s balance sheet policy allowed the government to run high deficits.

The Fed’s potential avenues for reducing balance sheet impact

We see three potential channels through which a Warsh-led Fed may even attempt to steer away from perceived monetary dominance. The first is through a new Fed-Treasury accord, where the Fed’s Treasury holdings continue or accelerate their paths towards neutrality. Actually reducing the size of the balance sheet is non-trivial. The central bank has formally adopted an ‘ample reserves’ regime, where the effective federal funds rate is effectively stuck to a lower bound close to the Fed’s interest rate on reserve balances, compared to a ‘scarce reserves’ setting where supply has to be frequently matched to demand to keep the market clearing rate within the range set by the Fed. These ample reserves critically rely on a substantial Fed balance sheet. This presents the remaining two ways in which the Fed may reduce the balance sheet; go back to a scarce reserves setting or adjust wider policy to change the level at which reserves become ‘ample.’ Before we dig into the potential scenarios, we should make it clear that while Warsh will (Congressional approval assumed as given) become the new Fed chair, he will not become Fed dictator. We are speculating on potential scenarios based on his commentary. We do not know his exact plans, and moreover, he may be prevented from implementing any plans he does have by the wider FOMC.

A Fed-Treasury accord

The 1951 Fed-Treasury accord established operational autonomy of the Fed in setting interest rates, following pressure from the Treasury to limit the cost of growing public debt, while the Fed wanted to raise rates to fight inflation. Warsh has claimed that the 1951 accord is at odds with recent practice, with the line between the central bank and fiscal authority blurring. What could such an accord look like in 2026? Warsh has advocated a new accord to provide a framework in which the Fed and Treasury, possibly also with the housing agencies, could coordinate to shrink the size of the balance sheet. That coordination is supposed to limit market volatility as the balance sheet shrinks and financial conditions tighten. Warsh seems happy to lower the policy rate to combat that tightening. The Fed standing ready to buy any bills the Treasury issues smells a lot like deficit financing, and could, and perhaps should, ironically be seen as a hit to the Fed’s independence, contrasting with the 1951 treaty that improved independence.

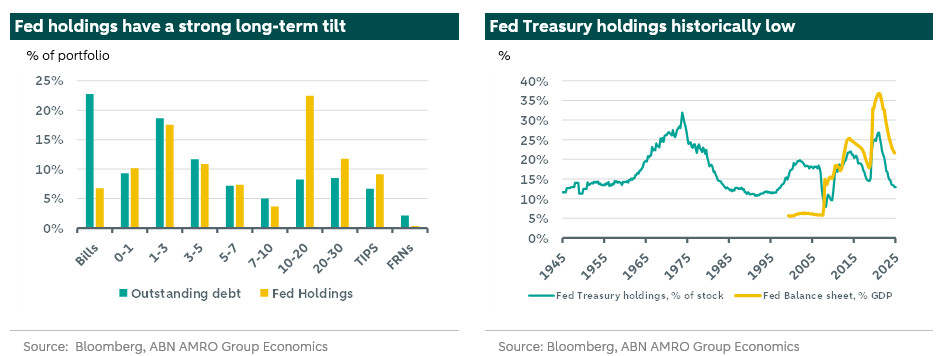

As opposed to actually shrinking the balance sheet, we believe a more likely outcome is a more market-neutral balance sheet, where the Fed shortens the maturity of its portfolio, by reinvesting maturing Treasuries into more short-dated government debt, in line with the duration in the market. This would also make it more consistent with pre-2008 balance sheet, where the Fed often held a larger share of total Treasuries than now but focused on shorter term debt. There are a number of ways the Fed may achieve this. The obvious one is a gradual roll-off where maturing debt is replaced with shorter maturities. An active sell-off seems less likely, as bringing just the 10-20yr back to market neutral would require a sell- or roll-off of more than 5% of total 10-20yr Treasuries outstanding, which would bring unacceptable market pressures. Beyond that, there is also a possibility of swapping the portfolio of mortgage backed securities for bills with the Treasury, in line with recent announcements of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac buying MBS to help mortgage costs.

Alternatively, we could see an off-the-market asset switch where long-term Treasuries are replaced with short-term treasuries. What might this look like in the coming year? There’s a substantial refinancing agenda. Most of the maturing debt this year is short-term bills that will likely just be rolled over. Out of the $691bn of Fed-held government debt maturing in 2026, about $124bn is in the 7-10yr bucket, $56bn in the 10-20yr bucket, and a mere $12bn in the 20-30 bucket. They hold about 14.5% of all maturing government debt this year, but more than 25% in the higher maturity segments.

Reverse Operation Twist

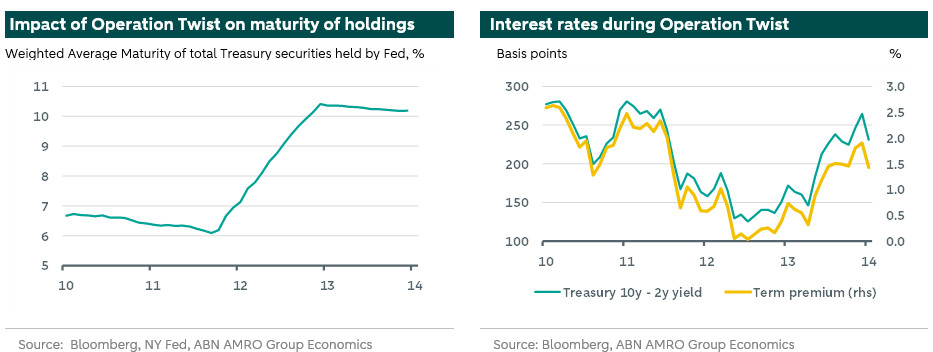

The Fed shortening the maturity of its portfolio would amount to a ‘Reverse Operation Twist’. The Fed has conducted an Operation Twist twice in its history, once in 1961 and more recently in 2011-2012 both with the intention of flattening the yield curve. Focusing on the more recent programme, the FOMC announced in September 2011 that it would purchase USD 400bn of longer-term U.S. Treasury securities to replace an equivalent amount of shorter-term securities. In June 2012, the FOMC extended this through the end of 2012, switching another USD 267bn of securities. Over the period of the programme, the average maturity of Fed holdings of Treasury securities surged from around 6 years to around 10 years (see chart below on the left) over a relatively short period. This significant increase in duration led to a flattening of the yield curve as it depressed the term premium (see chart below on the right) leading up to and during the programme. A Reverse Operation Twist exercise would have the opposite effects, all else equal.

Ample versus Scarce reserve policy

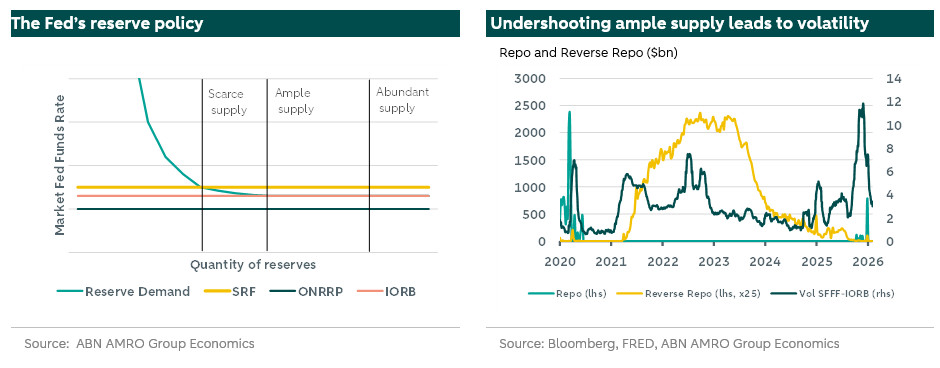

While the above option mainly marks a shift in duration of the Fed’s portfolio, it does not actually shrink the balance sheet. Shrinking the balance sheet is not a trivial exercise. To understand why, we need to dig a bit into the mechanics of the Fed’s reserve management. The Fed sets a 25bps target range for the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks borrow overnight, uncollateralized, from intermediaries. The lower and upper bound are the Fed’s repo (SRF) and reverse repo rates (ONRRP). There’s a third rate on reserve balances (IORB), which stands 10 bps below the upper limit. Currently, these three rates are 3.50, 3.75 and 3.65 percent. As the quantity of reserves increases, reserve demand becomes inelastic at roughly the IORB. That means that when supply is abundant, the market fed funds rate is anchored close to it. Ample supply is where supply sits just above the infliction point, minimizing the size of the balance sheet while keeping the Fed Funds rate at the IORB. Scarce supply is where supply interacts with the elastic part of the demand curve and the Fed funds rate starts to rise. In its 2020 framework review, the Fed formally adopted the ample supply setup, meaning interest rate control is managed through these rates, rather than active reserve management. The ECB and Bank of England run a similar setup.

As the chart above also shows, the Fed has gradually reduced the size of its balance sheet. Late last year, they decided to expand the balance sheet gradually again, as activity in the Repo market and volatility in the effective federal funds rate made it apparent they had come too close to the ample reserves threshold. Demand for liquidity is likely to grow, and as a result the balance sheet has to expand slowly to even maintain the status quo. In the December FOMC meeting, the Fed indeed announced that they resumed expanding the balance sheet to avoid liquidity pressure.

A reduction of the balance sheet size to pre-GFC levels is therefore essentially only possible if the Fed decides to adopt a scarce reserves policy again and goes back to active reserve management. That sounds like a simple idea but is extremely difficult in practice. Banks have adjusted their business models, liabilities shifted into more liquid uninsured deposits. Liquidity demand is probably permanently higher as a result, more on that later. Moreover, because of these dynamics, accurately predicting demand in order to match supply has become a lot harder. This will lead to large volatility in short-term rates. What is more, banks testing the upper bound of the rate may force the Fed to increase the balance sheet again, so success is not ensured.

Lowering banks’ reserve demand

The rise in reserve demand reflects changes in reserve management discussed above, but also changes in bank regulation, predominantly the introduction of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). The numerator in this ratio is high-quality liquid assets (HQLA), which are primarily reserves and US Treasuries. The main way to lower reserve demand is therefore to make it more attractive to hold Treasuries such that banks substitute. Banks currently prefer to hold reserves over Treasuries, primarily to avoid signals of distress. Banks don’t want others to see them selling Treasuries during a stress period. That could be done by removing the yield on reserves by setting the IORB back to zero again, but that would actually put us back in the reserve management setting. They could broaden what counts as Level 1 HQLA allowing for more alternatives to reserves. Regulators could exempt short-term Treasury securities from market risk buffers, allowing bank reserves to be replaced by Treasuries for HQLA. They could do something similar on the leverage side, exempting Treasuries, but not reserves, from leverage ratio calculations in the calculation of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). Banks could then expand Treasuries without needing to attract more capital.

The above makes clear that a small balance sheet and scarce reserve frameworks, even small movements in demand or supply could result in large swings in short-term money market rates. Such uncertainty would likely have a dampening effect on bank’s willingness to provide credit to the real economy. Shrinking the balance sheet is therefore fraught with peril, and we think that it’s unlikely that we’ll see a substantial wind-down of the balance sheet. A compositional shift towards shorter duration of the portfolio, potentially working together with the Treasury, seems like a more likely outcome, but it would be difficult to achieve this without some steepening of the yield curve. An offset of lower short-term rates might be a necessity to maintain financial conditions. We also expect supervisory policy to move in a direction that makes holding Treasuries more palatable. We’ve seen various suggestions over the past year of the Trump administration trying to have more demand for Treasuries from banks, and steps will likely be taken. It is not clear whether those changes in the demand curve would be sufficient to overcome the overall growth in tandem with GDP, but it might slow down further accumulation.

When theory meets reality

President Donald Trump has made housing affordability a cornerstone of his economic agenda and has made it clear that he wants to see mortgage rates fall. Shrinking the Fed’s balance outright or reducing the maturity profile would in each case put upward pressure on US Treasury yields and hence mortgage rates other things being equal. This suggests that there is a fundamental inconsistency between Mr Warsh’s plans and the objectives of the Trump administration. The Fed Chair elect has made the case that if a central bank has less of a footprint in the government bond market, this could encourage fiscal discipline and therefore eventually lower long-term interest rates. This argument seems to miss the ‘part in the middle’, that is, that higher longer-term interest rates would be needed in the first place to trigger the changes in fiscal policy.

An alternative scenario to temper the rise in long-term interest rates would involve the US Treasury attempting to mirror the decline in the average maturity of the Fed’s holdings through further shifts in its issuance policy. In effect, the US Treasury would be conducting its own Operation Twist to offset the Fed’s Reverse Operation Twist as part of a possible 2026 Fed-Treasury accord. Indeed, the Treasury has already been moving in this direction with more short-term issuance and buy-backs of long-term securities over the last year. It could accelerate this trend. However, preventing upward pressure on long rates might be easier said than done given the sharply rising funding needs of the US government. For instance the Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that debt held by the public would rise from around USD 30 trillion last year (99.4% GDP) to USD 56 trillion by 2036 (120.2% GDP). In addition, shifting the average maturity of outstanding government securities sharply lower would heighten refinancing risk. Given these considerations, any Reverse Operation Twist could turn out to be a gradual multi-year operation.