Sovereignty increases EU regulatory burden

Trade between European member states is less intensive than trade between the 50 American states. Consequently, the benefits of scale and specialization remain underutilized, resulting in lower productivity growth compared to the US. One reason for the disparity in trade intensity is the complex regulations that hinder the internal market. The complexity of European regulations is not primarily due to the inferiority of individual member states' regulations compared to those in the US, but rather the lack of harmonization among the member states. Simplifying rules, as the European Commission currently aims to do, does not necessarily resolve this issue. A truly unified, common market with low transaction costs becomes feasible when member states can no longer easily negotiate exemptions or establish additional rules. Therefore, member states will need to relinquish some sovereignty. Furthermore, new regulations should be consistently evaluated for effectiveness (do the rules achieve the intended outcomes?), efficiency (are these outcomes achieved at the lowest possible cost?), consistency (do the rules align with policies in other areas?), and enforceability (can compliance be effectively monitored?). This evaluation task was previously assigned to the European Commission. However, as the Commission's role has become more political, and compromises are often required to strike deals, it is less able to perform this task effectively. Consequently, this responsibility should be assigned to an independent body.

High EU regulatory burden hampers economic activity

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has introduced numerous new rules. Environmental concerns, climate change, and social inequality have played significant roles in political debates, resulting in the European Commission adopting greater ambitions in these areas. Additionally, technological innovations and digital transformation have led to societal shifts, prompting various measures to manage these changes. Between alone, European companies had to navigate five and a half thousand pages of legal texts.

Companies have voiced complaints about the increased regulatory burden, citing heavy administrative burdens and high costs of regulatory compliance. They highlight unclear and impractical definitions, duplications in reporting obligations to the agencies to which they must account, and rules that conflict with stated goals. Another concern is that goals are not always pursued in the simplest and most financially advantageous manner. The annual administrative burden is estimated at , encompassing direct burdens. Indirect burdens, such as companies refraining from certain investments, are not accounted for.

Two-thirds of companies believe that hinders investments and innovation capabilities. Regulatory complicates swift responses to changing market conditions and shifting consumer preferences. Additionally, the EU is a less attractive location for establishment due to lengthy procedures for permit applications. This is particularly true because the common market —free movement of goods, services, capital, and people— exists mainly on paper. Persistent trade barriers and lack of common standards prevent the full realization of potential scale and specialization benefits.

Simplified and harmonized regulations strengthen common market

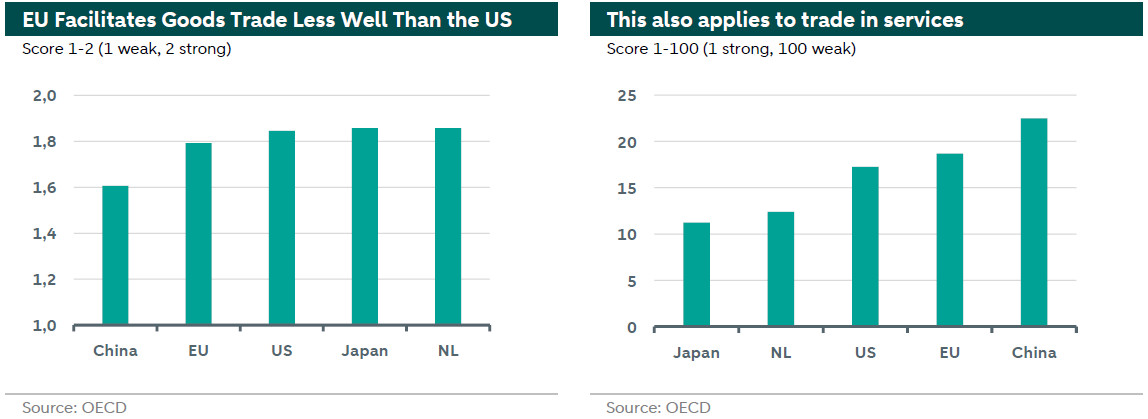

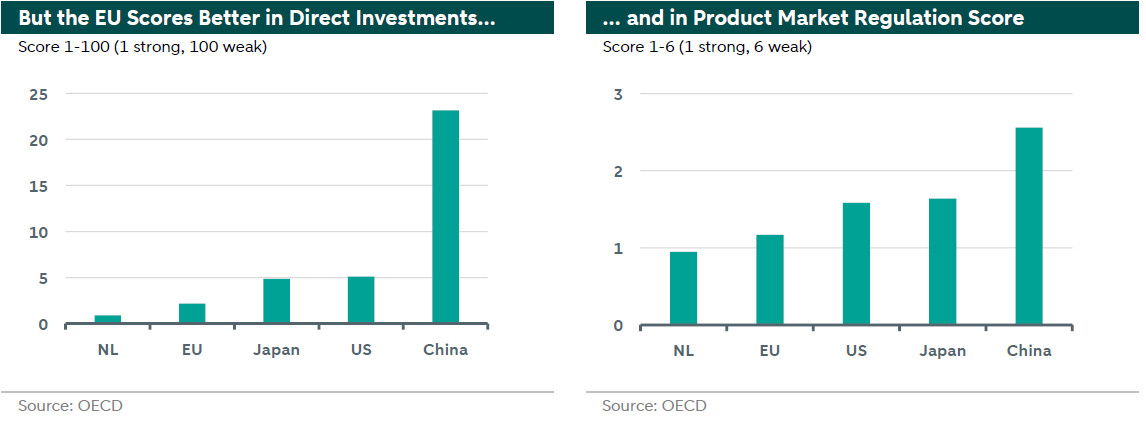

According to OECD statistics, the situation is not that bleak. The OECD scores countries’ regulatory systems. When the scores of European member states are aggregated by GDP weight to arrive at an average European score, it appears that while Europe faces more restrictions in than the US, it performs better in and .

The problem of regulatory burden does not lie so much in the regulations of individual European member states but in the aggregate combination. Analysis by the shows that the burdens of all trade barriers between European member states equate to an import duty of 45% for goods and an import duty of 110% for services, which is three times higher than in the US This difference explains why trade within Europe is half as high as between the 50 American states. This means that opportunities to achieve scale and specialization benefits and thereby increase productivity remain underutilized.

International trade with the rest of the world as a percentage of GDP is higher in Europe than in the US This suggests that trade restrictions at the external borders are less obstructive than in the US. Europe has increasingly opened its external borders but has failed to remove barriers at the internal borders. If internal trade barriers were reduced to the American level, European productivity could increase by 7%, effectively halving the productivity gap between Europe and the US This bonus would be highly welcome and could be utilized to address the burdens of various shared challenges, such as improving energy infrastructure and bolstering defence.

Resolving internal obstacles

The lack of harmonized regulations affects various areas, including the labour market. For example, within Europe are eight times higher than in the US, partly because transferring accrued pension rights is challenging. High relocation costs prevent workers from maximizing their talents, making it harder for companies to find suitable personnel, which impacts investments. Streamlining European labour markets, modelled after the best-performing countries, can increase labour mobility.

Additionally, there are relatively few opportunities for . In the event of an economic shock, 70% of the impact in Europe is absorbed by national member states, compared to 25% by individual states in the US Without a fiscal union and a fully-fledged common capital and credit market, sharing risks through tax revenues, wealth transfers, and lending is more challenging. As a result, the risk of investing in the EU is higher than in the US, leading to lower and more conservative European investments. This results in lower R&D spending and limited innovation capacity.

European Commission wants to reduce the regulatory burden (again)

The Draghi report rightly emphasizes the need to simplify regulations, an important step towards improving competitiveness. The European Commission takes this recommendation seriously. Economy & Productivity Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis has been tasked with reducing administrative burdens for all companies by 25%, amounting to EUR 37.5 billion. Relief should primarily be directed at SMEs, as they are more affected by regulatory burden. For instance, European SMEs are less likely to expand across borders than larger companies because they find it more challenging to muster the necessary knowledge and manpower.

The first step towards lightening the regulatory burden was taken by the European Commission on February 26. The Commission presented a first to lighten reporting obligations regarding sustainability. The number of companies in scope based on turnover and number of employees has become more limited. More omnibus packages of reform proposals followed and will be submitted for approval to the European Parliament and the European Council.

It is not the first time the European Commission has aimed to reduce regulatory burden. As early as 2006, the Commission proposed reducing regulatory burden by a quarter, and six years later, a report concluded that this goal had been achieved. However, the problem was not solved, as two years later, the Commission again declared its intention to cut rules. In 2022, the REFIT program, aimed at identifying and eliminating unnecessary rules, was replaced by the 'Fit for Future' program. That year also saw the adoption of the 'one-in-one-out' principle, where each new rule would replace an old rule. In short, there are plenty of good intentions. But do they bear fruit?

Eliminating rules is not necessarily a good idea

Unfortunately, it's challenging to determine whether efforts to eliminate rules have been successful. The number of rules is not tracked, which anyway does not make much sense given the considerable variation in the types of rules. EU legislation consists of various legal instruments such as treaties, regulations, directives, decisions, and recommendations, each with its own purpose and legal force. The European Commission's ambition to reduce regulatory burden thus mainly serves a symbolic function. This impression is reinforced by the fact that it is impossible to determine whether eliminated rules posed obstacles for companies or facilitated their activities.

Rules can be useful and help achieve certain societal goals. They are sometimes required to correct market failures and allow markets to function properly. Competition rules, for example, prevent companies from unlawfully acquiring market power and abusing it to exclude competitors unfairly. By combating monopolies and cartels, competition is stimulated, ultimately leading to more innovation, better products, lower prices, and more choice for consumers. Additionally, rules can contribute to politically formulated goals such as tackling climate risks and environmental pollution through reporting requirements or improving public health by setting minimum standards for housing and working conditions.

Deregulation is not advisable if this undermines the original purpose of the regulations. That is precisely why eliminating rules is difficult in practice. Simplification often leads to narrowing the scope of regulations by giving companies more time to comply or by reducing the number of companies required to comply, as occurred on February 26 with the first omnibus law. Such reforms provide temporary relief but do not offer a long-term solution.

Good regulation requires discipline

For a more long-term solution, it is important to examine how regulations are created and how this can be improved. There are guidelines from the OECD for this. They first prescribe that an impact assessment is needed, which considers alternative policy options, including the 'do nothing' option. These options should then be objectively, impartially, and consistently weighed against each other. The analysis should show that the benefits of new rules outweigh their direct and indirect costs and that they are coherent with policies from other governance levels and measures in other policy areas, so that rules reinforce rather than weaken each other. Secondly, those affected by new rules should be consulted. All involved parties should receive timely information about which rules will be implemented when and what their rationale is. This contributes to transparency and support. Thirdly, it is important to monitor rules after implementation to assess their effectiveness and, if necessary, adjust them.

Following these guidelines requires administrative discipline. This discipline was previously ensured by the European Commission. As a technocratic body within the EU, its priority was to create sound legislative proposals and independently monitor compliance with agreements made by member states. After successive crises in recent years, however, the European Commission has gained more powers, and its role has become more political. Many decisions require unanimity, prompting the European Commission to regularly make exceptions for individual member states, either in the form of 'opt-outs' (the regulation or parts thereof do not apply) or in the form of 'gold-plating' (member states may impose additional requirements). Both options lead to fragmented regulations and additional regulatory burden. In other words, they are a form of non-tariff barriers between member states.

Due to the European Commission's more political role, the importance of high-quality impact assessments and consultation rounds has increased. Confidence in these can be boosted by placing the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, an independent body within the Commission that advises the College of Commissioners that provides quality control, more at arm's length from the European Commission and providing it with sufficient financial and personnel resources to conduct these impact assessments and consultation rounds. These should be performed more frequently than is currently the case. Furthermore, these should be taken more seriously, not only by the European Commission but also by the European Council and the European Parliament.

In addition, a more fundamental adjustment could be appropriate: limiting the veto right. If member states give up part of their sovereignty and have less room for 'opt-outs' and 'gold plating', it would be an important step towards more harmonized, simpler European regulations. Considering the outcome of recent European Parliament elections this is likely a bridge too far: nationalist parties that opt for less rather than more Europe gained seats. These parties will not be in favour of transferring power to Brussels.