The Ugly Contest: Part I - Can France dig itself out of a fiscal hole?

France wins the Ugly Contest for now, but the UK has its own major risks

While both France and the UK are facing difficulties putting their debt on a sustainable trajectory, France wins the Ugly Contest for now

Political paralysis, and the eurozone safety blanket, are keeping France from taking the painful steps needed to regain control of spending

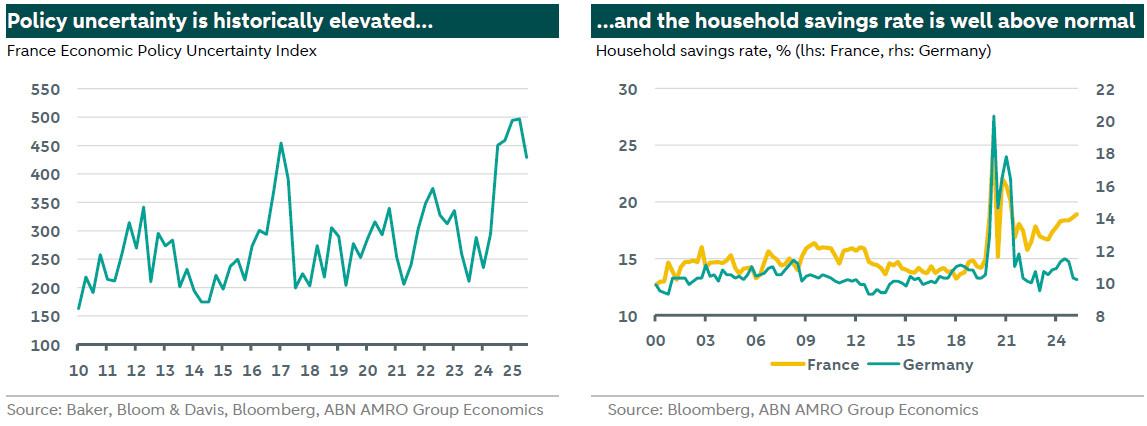

Low nominal GDP growth makes this job even harder, while policy uncertainty is eroding confidence, pushing households to save more

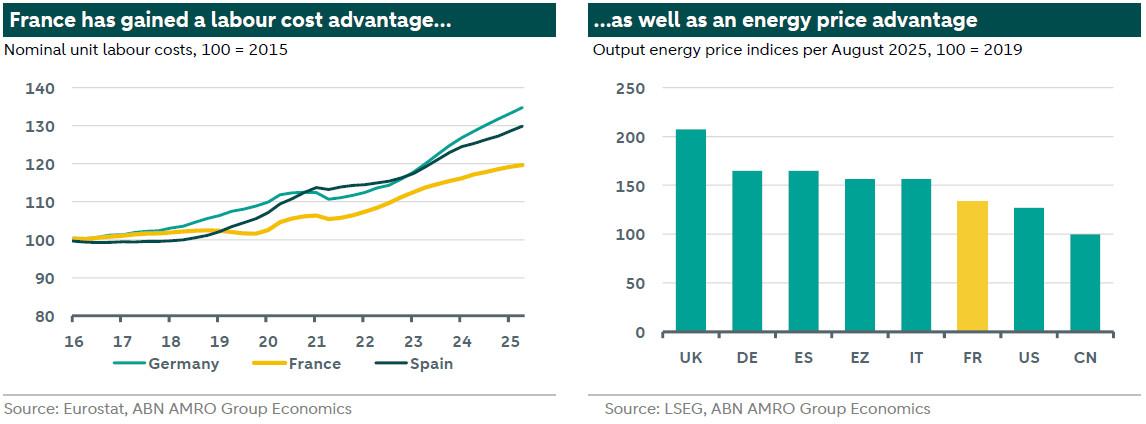

Competitiveness gains in labour and energy offer hope, but a growth pickup would be insufficient by itself to restore France to fiscal health

Our base case sees France muddling through, with a high risk of another snap election, and/or the election of a populist government

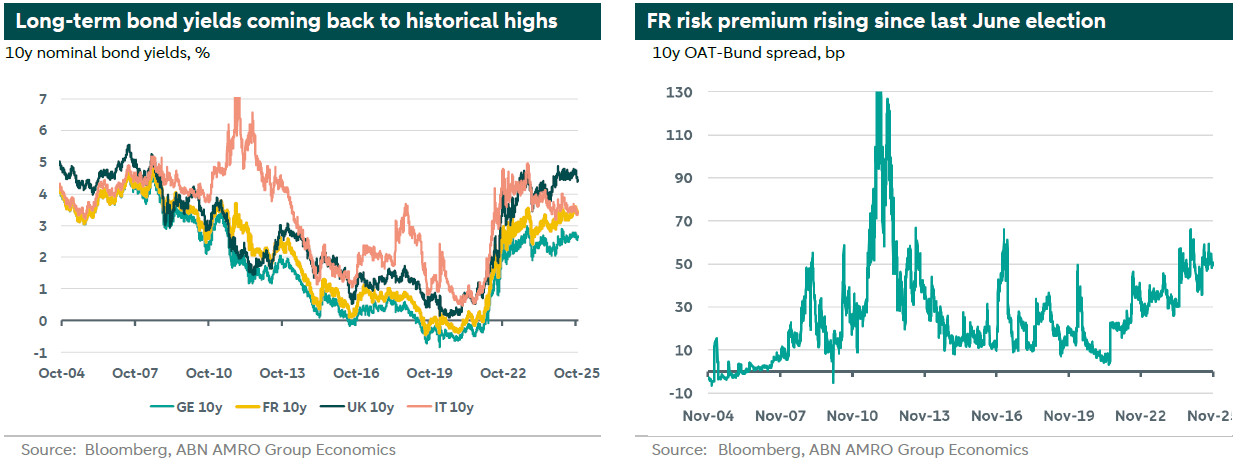

France’s bond market spread over Germany is likely to remain elevated

A renewed spike in spreads could occur if the government fails to pass a 2026 budget, or if there is a snap election

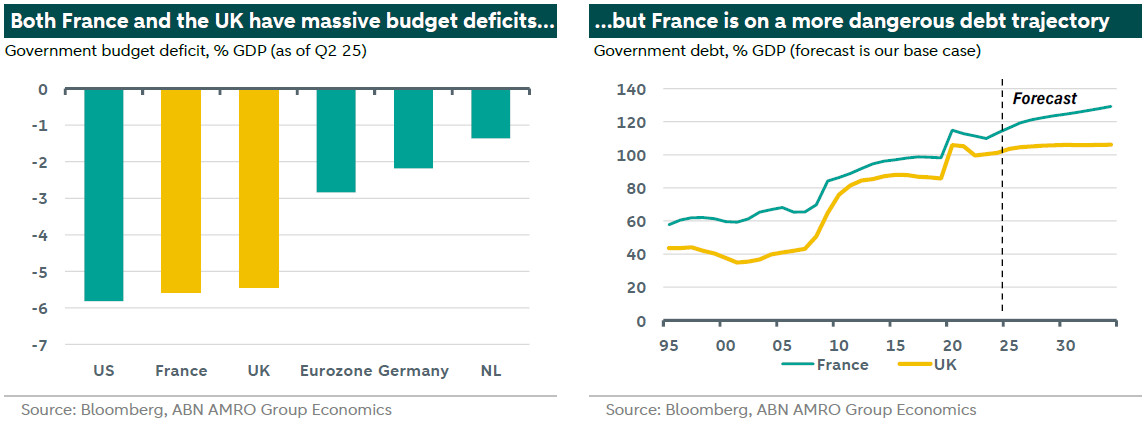

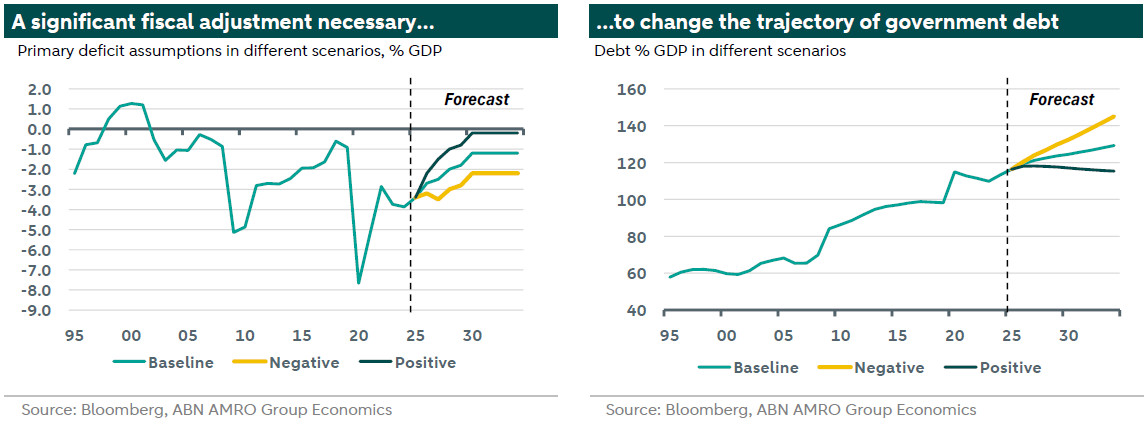

France and the UK’s fiscal woes have been a regular theme in the financial markets news cycle in recent years. If the various headlines – and bouts of bond market stress – are taken at face value, both are in a dire fiscal situation, perhaps even a doom loop of low growth and unsustainable debt. Or are they? In this special series, we look at the fiscal health of both countries and find that – contrary to appearances – France is in a much more difficult position than the UK. Over the coming years a truly heroic fiscal adjustment, of around 5 percentage points of GDP, will be needed to put debt back on a sustainable trajectory. This looks implausible in the current political environment; more likely is that France continues to muddle through and delay the inevitable reckoning until a crisis forces its hand. In a more benign scenario, if France is able to harness its competitiveness gains in recent years vis-à-vis eurozone peers and grow more quickly, a less dramatic fiscal adjustment may be necessary. The UK, in contrast, has broadly stuck to its fiscal rules, and is much more likely to see a downward sloping debt ratio by 2030 than France is. But the UK faces its own significant risks over the coming years, the biggest being the possible election of a radical right-wing government in 2029. Such a government could seek to exert the same political pressure on the Bank of England that we are seeing now in the US with the Federal Reserve. The main risk in the UK could then transfer from bond markets to the currency. This is something we will tackle in the next part of our series.

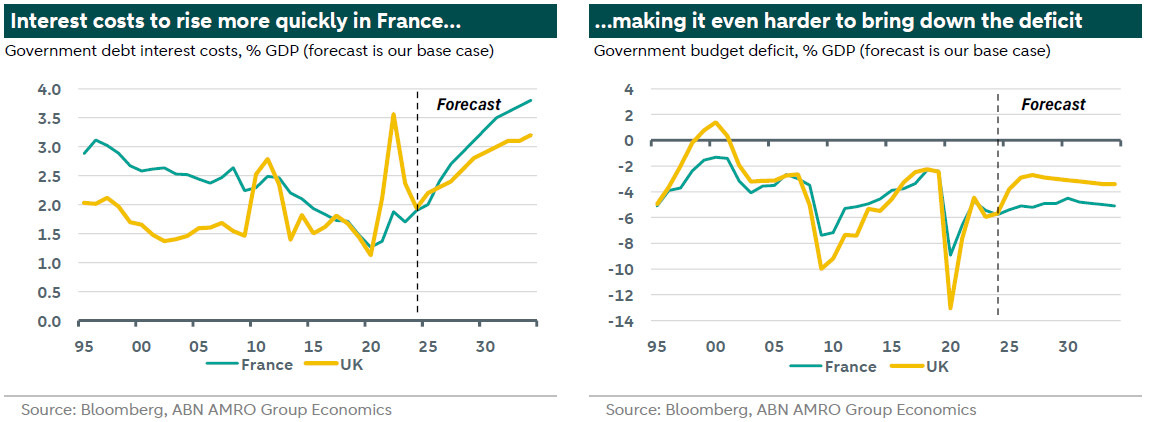

France: A mammoth effort needed to right the fiscal ship

France definitely wins the Ugly Contest if we look purely at medium-term debt dynamics and risks. Following a deficit of 5.7% of GDP in 2024 – nearly double the EU’s fiscal rule of 3% – successive minority governments have struggled to get a 2026 budget through the Assembly that would return the deficit to more sustainable levels. To put politics and France’s structural spending problem aside for a moment (see Box), France has to run just to stand still: the interest burden is set to rise rapidly in the coming years, with interest payments set to double from around 2% of GDP this year to nearer 4% by the 2030s. This means that France has to implement significant spending cuts and/or tax rises merely to keep the deficit at the current very elevated level. To then bring the deficit down to a level that would put the government debt ratio back on a downward trajectory would require an adjustment in the primary balance (i.e. the deficit excluding interest costs) of around 5 percentage points of GDP over the coming years – not far off the adjustment seen in the likes of Spain and Portugal at the height of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis. This is where the size of France’s current debt burden plays a role, because although the UK has higher interest rates, France’s higher (and rising) debt ratio means that its interest costs are set to rise much faster than in the UK over the coming years.

-----------------------------------------------------------

Box: Latest developments on the 2026 budget, and France’s structural tax-and-spend problem

Following the previous Bayrou government’s failure to pass a budget that would have brought the deficit down to c3% by the late 2020s, the minority Lecornu government has sought a more conciliatory but much less ambitious fiscal consolidation path. His target is now for a more modest reduction in the deficit, from a projected 5.4% of GDP in 2025 to 5% in 2026 – around half the fiscal consolidation targeted by Bayrou (who had a 4.6% deficit target for 2026). Part of this involved a concession to the Socialists to suspend the controversial rise in France’s pension age from 62 to 64. Since then, the Socialists have made further demands, including a new wealth tax (the so-called ‘Zucman tax’). This has since been voted down by the Assembly, although the government last week introduced its own amendment to raise corporate taxes on large firms, as a means to try to keep the Socialists on board. It remains to be seen if this will be enough.

We continue to think it will be difficult for the government to pass a 2026 budget, leaving the possibility of other ways forward on the table. PM Lecornu has said he would avoid using article 49.3 (the same mechanism that was used for the pension reform) to overrule the Assembly. Another option, if the Assembly fails to reach a decision by December 23rd, would be to implement the budget via government decrees (known as “les ordonnances”). If this unprecedented route is taken, the initial draft bill submitted by the government would be adopted as-is (i.e. aiming to reduce deficit to 4.7%). While this may appear favorable from a fiscal perspective, it also heightens the risk of an early election, as many parliamentarians would deem the approach undemocratic. "If ordinances act as a pseudo 49.3 article, censorship will follow," warned Olivier Faure, the leader of the Socialist Party. As a last resort, the government could simply seek to rollover the current budget to 2026. This would be a negative scenario from a fiscal consolidation standpoint. According to the Finance Ministry, this would cost the French economy approximately EUR 11 billion, further exacerbating the budget deficit (estimated to rise to around 5.5% in that case). However, even this would be better than another snap Assembly election, which would lead to a renewed rise in uncertainty and potentially a government that has little interest in fiscal consolidation. The risk remains high for another snap election, though it is not our base case. Probably the only party that would gain from this would be the far right National Rally, and so there would be little incentive among President Macron’s centrists and those on the left to go down this route.

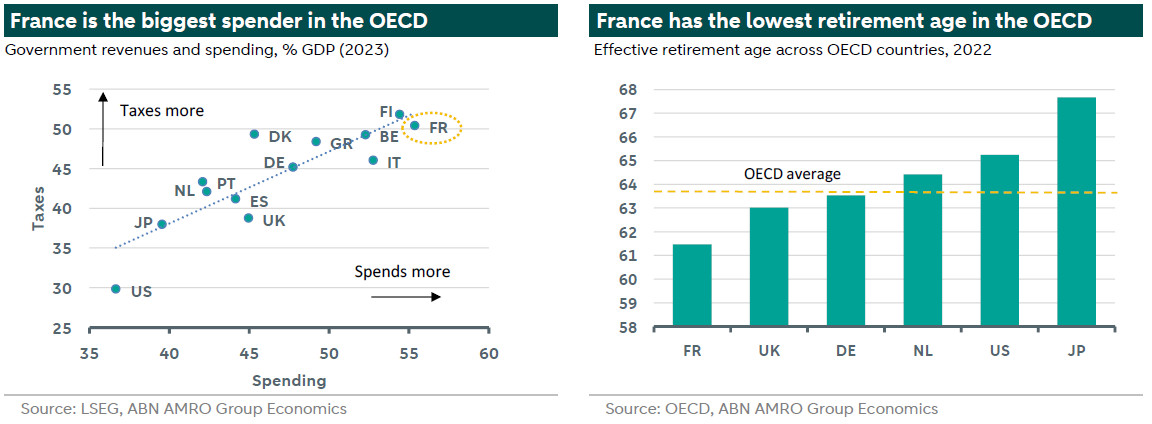

France tops the tax & spend league tables

Over the past few decades, France has structurally raised its spending, and whenever fiscal consolidation has been called for, successive governments have generally resorted to tax rises rather than spending cuts. This has culminated in among the highest tax-and-spend ratios in the OECD, with only Finland taxing somewhat more – but spending somewhat less – than France (see chart below). Indeed, government taxes are now probably approaching the limits of how high they can go, in that further rises run the risk of raising less revenue due to their negative impact on economic growth. A wealth tax could have some economic rationale, if it shifts the tax burden from income towards wealth: this could increase labour supply by strengthening the incentive to work. However, the so-called ‘Zucman’ tax that has dominated the debate in France recently has been promoted largely as means to avoid spending cuts rather than to lower income taxes. In addition, wealth taxes could lead to capital flight that blunts any increase in tax revenue. Given the risks associated with further raising the tax burden, a much more effective means of cutting the deficit would be to lower spending but in a way that enhances rather than subtracts from economic growth. To take a pertinent example, the politically sensitive rise of the retirement age (now suspended) would not only mean lower spending, but it would most likely have a net positive effect on economic growth by increasing labour supply. Moreover, viewed from an international context, the reform to the retirement age was a relatively modest one. In 2022 (on the eve of the reform), France’s effective retirement age was the lowest in the OECD and well below the average, while France’s post-retirement life expectancy was among the highest in the OECD.

There is no magic formula. Ultimately, for France to successfully rein in its public deficit and debt ratio, government spending must decrease. As discussed below, even if France were to grow more rapidly over the coming years, this would be nowhere near enough by itself to put government debt back on a sustainable trajectory. The adjustment of peripheral economies such as Spain, Greece, and Portugal should serve as examples to follow.

-----------------------------------------------------------

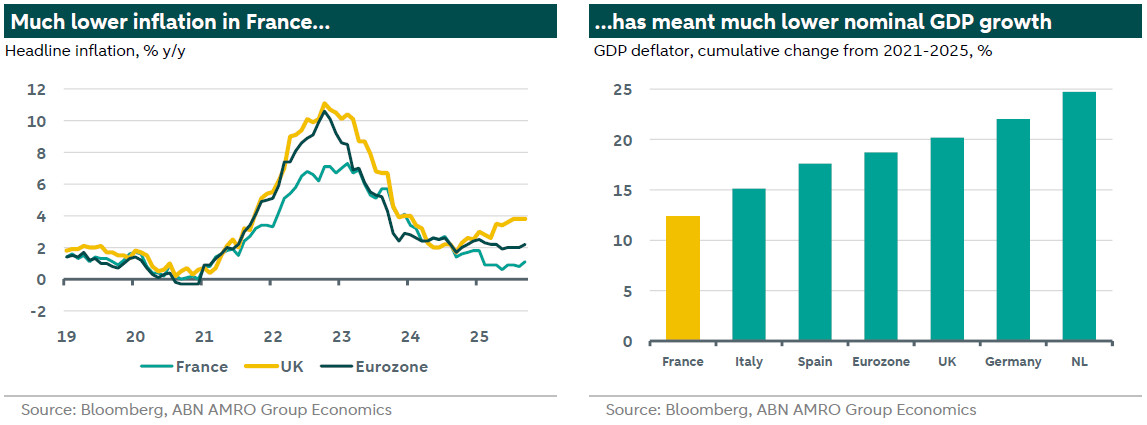

Low nominal GDP growth makes fiscal consolidation even harder

Compounding France’s fiscal woes is its low nominal GDP growth. Since late 2021, France’s GDP deflator has risen by around 12% - far below the eurozone aggregate (19%) and almost half the pace of some of its neighbours (see chart below). This has its roots in the French government’s unique policy response to the energy crisis. While most European governments gave households cash handouts to compensate for high energy bills, France imposed strict price caps on energy suppliers. This meant that the peak in inflation in France was much lower, but crucially, the second round effects – wage growth and broader inflationary pressure – were also much lower. The problem was not the policy itself, but the fact that it differed so much from other eurozone countries. Because the ECB sets monetary policy for the eurozone aggregate, the Governing Council’s steep interest rate rises and were arguably inappropriate for the milder inflation shock in France. Indeed, inflation in France is currently well below the eurozone aggregate at 1.1% y/y as of September, and of course well below the ECB’s 2% target, suggesting that even now rates are much too restrictive for France’s economic circumstances[1].

The impact of this policy mismatch is twofold. First, much lower nominal GDP growth means a much lower dominator in debt metrics, boosting the debt to GDP ratio. Second, with policy rates too high for France’s economic circumstances, the interest burden is also considerably higher than it needs to be to keep inflation at the 2% target.

Is a Liz Truss crisis looming for France?

We see two main triggers that would move France out of its current ‘muddling through’ limbo. The first is if there is a decisive electoral victory in 2027 (or earlier, in a snap election scenario) delivering a solid majority either to a fiscally loose government (either far right or far left), or the other extreme of a fiscally prudent government (more centrist). In the first scenario, a fiscally loose government would ignore bond market worries and row back on fiscal consolidation efforts. This would bring forward the reckoning with financial markets, and test the ECB’s resolve to intervene or not. Such an event could well bring a ‘Liz Truss’ moment to French politics if the public sees firsthand the impact of financial market stress, for instance via mortgage rates as happened in the UK. This would then cause a change in government to a more fiscally prudent one, again as happened in the UK. In a more benign scenario – where a fiscally prudent government is elected with a decisive majority – the ‘Liz Truss’ crisis is skipped and the government implements fiscal consolidation without market pressure to do so. This seems rather optimistic, however.

The main alternative to the above political pathways are more purely market-driven. For instance, a fiscal crisis elsewhere – like the US – leads to a global sell-off in bond markets, with markets then becoming newly worried about other fiscally unsustainable sovereigns. A classic case study here was in the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, where the crisis in Greece ultimately led to contagion to other bond markets, namely Ireland, Portugal and Spain. Such a crisis would eventually lead to much more aggressive fiscal consolidation in France, and probably a recession, as during the eurozone debt crisis.

What does all of this mean for the economy?

Needless to say, none of this is good for the economy. According to Banque de France, policy uncertainty is knocking around 0.2pp from annual GDP growth, while the OFCE estimate is almost double that, at around 0.4pp for 2025. This is corroborated by other indicators. For instance, the household savings rate has risen from already elevated levels over the past year to 19% of disposable income, some 5 percentage points above the pre-pandemic norm of around 14%. For comparison, the savings rate in Germany has broadly returned back to its pre-pandemic level of around 10%. While it is hard say how much of the rise in savings is driven by fiscal policy uncertainty, it cannot have gone unnoticed by households that the French government faces pressure to raise taxes or cut spending, or some combination of the two, with households probably raising precautionary savings in preparation for this. Indeed, this could well be a concrete empirical example of Ricardian equivalence – the idea that government borrowing does not affect overall demand in the economy, because people anticipate that today's borrowing will lead to higher taxes in the future.

Beyond households, there are also early signs that France’s wealthy are moving assets to other neighbouring jurisdictions to avoid possible future wealth taxes. This suggests that the government may as well bite the bullet and implement fiscal tightening anyway given that society is already behaving as though it is. Put another way: there appear to be limited growth benefits from putting off fiscal consolidation.

Growth to stay below trend in the coming years…

All of this is likely weighing on consumption and investment growth in France, and this is expected to continue going forward. What about defence spending as a growth saviour? While France clearly has the political ambition to raise defence spending, its lack of fiscal space means that it is unlikely to raise spending by anywhere near the magnitude expected in neighbouring Germany. We expect most of France’s extra defence spending over the coming years to lean on the EU’s new SAFE fund, of which around EUR16bn (0.5% of GDP) has been allocated to France, while it may also benefit from some spillovers from higher German spending. But we do not expect this by itself to be a game changer. Finally, the government’s suspension of the rise in the retirement age is also a negative for growth given that this reduces labour supply. All told, we expect GDP growth in France to remain at a subdued, below trend 1% and 1.1% in 2026-7, rising only gradually from the projected 0.9% for 2025.

…and inflation well below 2%

Crucial for debt dynamics is continued low demand-side inflationary pressures. Inflation in France has been below 2% for more than a year now, almost half of that time even below 1%. With demand weak and downward pressure if anything likely to intensify over the coming months on the back of falling oil prices, we expect inflation to stay below 2% throughout 2026-7. Coming alongside weak GDP growth, we expect this to keep nominal GDP growing at just 2% on an annual basis in the near term, before picking up somewhat towards 3% in the course of 2027. As discussed earlier, this is a bad combination for debt dynamics, and will make the fiscal adjustment process of the French government considerably harder than if inflation were running higher.

Could cheap French labour costs save the day? (No, seriously)

There is one upside from France’s low inflation that we have yet to discuss: it has made the country more competitive. In relative terms, Germany’s unit labour costs have risen some 13% more than France’s over the past 10 years. France’s labour cost competitiveness has also improved relative to the Netherlands (14% higher), Spain (9% higher) and Belgium (6% higher). This is because wage growth has significantly lagged other countries. As discussed earlier, this is likely linked to the lower peak in inflation during the energy crisis and therefore less demand from workers to compensate for the loss to purchasing power. France has also gained a competitive advantage in another key production cost input: energy prices. In most eurozone countries energy prices are still around 50% higher than pre-energy crisis levels (in the UK they are double), but in France the rise has been contained to around a 30% rise – comparable to the US. France’s lower energy prices are likely in part thanks to its extensive fleet of nuclear power stations, making it less vulnerable to high LNG prices.

These competitiveness gains have some parallels with the sovereign debt crisis. Back then, talk was of crisis countries needing to undergo an ‘internal devaluation’ as an alternative to exiting the euro to regain competitiveness and to export their way back to debt sustainability. This involved holding down labour costs while those of competitor countries continued to rise. This by itself was no silver bullet – significant fiscal consolidation was also necessary – and it was a painful process. But it is arguably one of the reasons that countries in the periphery have grown faster in recent years than core countries. France could, in theory, see this competitive advantage draw more economic activity to it over the coming years, driving higher growth. Higher economic growth would not by itself be enough to fix France’s debt problem, but it would certainly help. For instance, the economy growing 0.2pp faster and inflation returning to the 2% target sustainably would reduce the necessary fiscal consolidation by around 1pp.

Rates Outlook: Should France fear the Bond Vigilantes?

Economic fundamentals, particularly fiscal and debt ratios, are critical metrics that investors closely monitor and serve as major drivers of long-term bond yields. This is particularly true when the buyer of last resort – the central bank – withdraws from the debt market, leaving governments to seek new buyers for their bonds. Over the past decade, Quantitative Easing (QE) played a crucial role in compressing sovereign risk premiums to historically low levels. However, as QE came to an end, it triggered a normalization of the term premium, leaving fiscally constrained countries, such as France (as well as the UK, which will focus on in the next note), more exposed to market volatility. As a result, markets have begun repricing France’s risk premium higher, and this is particularly impacting long-term debt such as 10y and 30y bond yields (see graph below).

Furthermore, the market is not only assessing current fiscal dynamics negatively but also expressing concerns about the broader outlook for the country. Political gridlock has heightened doubts regarding the government’s ability to implement swift and effective measures to restore public finances to a sustainable trajectory. This fiscal looseness has already resulted in credit rating downgrades, placing France at risk of losing its AA rating.

France’s borrowing costs relative to Germany (the OAT-bund spread) widened by more than 30bp after President Emmanuel Macron called snap legislative elections last year. Subsequently, successive government collapses stemming from attempts at trimming the deficit further increased market volatility surrounding French debt, causing the spread to remain in the 75- 80 basis point range. Still, the OAT-bund spread remains well below its historic record (during the eurozone debt crisis) of 130bp. Markets therefore seem to be pricing in the political deadlock, for now, rather than a debt crisis.

In our view, the primary reasons financial markets have been less nervous about France’s debt sustainability than other countries, such as the UK, is the presence of institutional safeguards within the eurozone, including the ECB. These institutions can act as a backstop if necessary, helping to reassure markets and prevent a sharp sell-off in French debt. Although France is not eligible for the ECB’s official bond market intervention mechanism, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), as it is under the European Commission’s Excessive Deficit Procedure, there remains a widespread belief – rightly or wrongly – that European institutions would not tolerate a financial crisis in France, essentially that it is "too big to fail." Additionally, Mario Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes” pronouncement in 2012 reassured markets that, should another sovereign debt crisis occur in Europe, the ECB would ultimately step in if the situation became crisis-like (see our recent note and podcast where we touch on this topic). This has arguably been one of the main reasons we have yet to see the kind of Liz Truss-style bond market event in France.

Obviously, this also has its limits, as a populist party taking control of the government and implementing reckless economic and fiscal policies is unlikely to go unnoticed by the market. Such a scenario would likely prompt the market to test the ECB backstop. In this more dramatic case, we believe that European institutions would only agree to intervene if the country commits to fiscal consolidation. Otherwise, this could lead to significant moral hazard and undermine the credibility of the central bank.

Is the ECB backstop a double-edged sword?

As we will outline in our upcoming Rates Outlook, given the challenging political situation, we anticipate that French debt will remain under pressure, keeping its spread relative to Germany (and other countries) at historically wide levels. The market appears to be largely in a "wait-and-see" mode, focusing on upcoming budget negotiations for next year and the next presidential election before adopting a definitive stance on French debt. While bond markets have since calmed, failure to pass a 2026 budget or another fall of government would trigger another bond sell-off and lead to an even wider spread. Ultimately, a "Liz Truss moment" might be what France needs to finally implement meaningful fiscal discipline.

For now, however, the implicit ECB backstop is insulating French politics from the pressure that is probably necessary to implement painful fiscal consolidation. For this reason, in our base case the path of least resistance will be for government(s) to shy away from the fiscal consolidation that would be needed to restore debt sustainability. In our base case, we assume some modest progress in bringing down the primary balance, with around 1pp in fiscal consolidation expected by the time of the presidential election in 2027. However, the rising interest burden will keep the overall government deficit nearer 5% of GDP – far above the EU’s fiscal rules stipulating a maximum 3% deficit. This is expected to keep the debt ratio rising to 121% of GDP by 2027, up from 113% in 2024. This assumes that interest rates follow our baseline, with the ECB keeping policy rates on hold.

-----------------------------------------------------------

Box: What a positive or negative scenario might look like for French government debt

Debt ratio forecasts are subject to a lot of moving parts, with sometimes small shifts in underlying assumptions completely shifting the trajectory. In our baseline of somewhat below trend growth and inflation, benign interest rate developments (with the ECB eventually moving back to our neutral estimate of 1.5% in the late 2020s), and a ‘muddling through’ fiscal consolidation of the primary balance, France’s debt ratio continues to rise gradually over the coming years. While debt is unsustainable over the long-run, it is probably not enough by itself to trigger a bond market crisis. What if circumstances are more – or less – benign than in our baseline scenario?

In the below scenarios we illustrate what different assumptions around interest rates, deficit reduction and economic conditions would mean for debt sustainability. A key insight from this is that even with more benign assumptions for growth, inflation and interest rates (the positive scenario), a sizable adjustment in the primary balance (c3pp) would still be necessary to return debt to a downward sloping trajectory. In a more negative scenario, where less fiscal consolidation is accompanied by even weaker growth and inflation – alongside somewhat higher interest rates – debt starts to rise very rapidly, to the extent that it risks a crisis in government bond markets.

-----------------------------------------------------------

[1] This points to a key pitfall of operating a common monetary policy with significantly divergent fiscal policy. Governments could seek to avoid this by better coordinating crisis responses at the European level.