ESG Economist - An introduction to nature-related risks

Economies are deeply reliant on ecosystem services like food, water, and climate regulation, yet alarming trends reveal the rapid degradation of critical natural ecosystems.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (2022) seeks to halt biodiversity loss by 2030, setting ambitious goals for governments, such as conserving 30% of critical ecosystems

Addressing these challenges requires action not only from governments but also from financial institutions

Financial portfolios depend heavily on nature’s ecosystem services, but the materiality and timelines of nature-related risks to financial stability remain uncertain

This note examines how the decline of pollinator populations could disrupt food production, driving inflation, reducing GDP, and threatening financial stability

Introduction

Economies are deeply intertwined with nature, relying heavily on the continuous flow of goods and services it provides, such as food, raw materials, pollination, water filtration, and climate regulation. However, numerous indicators reveal alarming trends regarding the state and health of natural ecosystems. For example, 75% of the Earth’s ice-free land has been significantly modified by human activities, and the population of vertebrate species has declined by nearly 70% since the 1970s .

In response to these trends, countries and states have embraced the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), an international agreement adopted in December 2022 during the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. The framework's core objective is to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, with 196 nations committing to address nature degradation and safeguard biodiversity. It establishes ambitious global targets to be achieved by 2030, such as the "30 by 30" initiative, which calls on policymakers to conserve and manage at least 30% of terrestrial and inland water areas, as well as marine and coastal regions, particularly those critical for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, by the end of the decade.

However, addressing these challenges is not solely the responsibility of governments. Institutional investors must also integrate nature into their decision-making processes. A critical step is for these institutions to assess the potential scale and materiality of the economic and financial risks stemming from biodiversity loss and environmental degradation within their balance sheets. However, Central Banks, regulators, and financial institutions appear to be at a similar stage to where they were 5–10 years ago with climate change risks—facing the need to catch up and develop robust frameworks to address these emerging challenges.

This recognition has motivated us to launch a new series of notes focusing on nature-related risks. In this first note, we aim to set the stage by qualitatively explaining what nature-related risks are, supported by a case study of how a physical risk could impact both the economy and the financial system. In subsequent notes, we will delve deeper into the numbers, analysing the macroeconomic impact of both physical and transition risks to nature.

How do nature-related negative shocks impact the economy?

According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), ecosystem services are defined as “the benefits that people obtain from ecosystems.” These include provisioning services, such as the supply of food and water; regulating services, such as flood and disease control; and cultural services, including recreation, ethical and spiritual values, education, and a sense of place.

Recent studies conducted by central banks, including De Nederlandsche Bank and the European Central Bank, have highlighted the significant dependence of financial portfolios on nature-related services. However, it remains unclear whether these dependencies constitute a material risk to financial stability—comparable to other environmental and non-environmental risks—or the timeframes in which such risks might emerge.

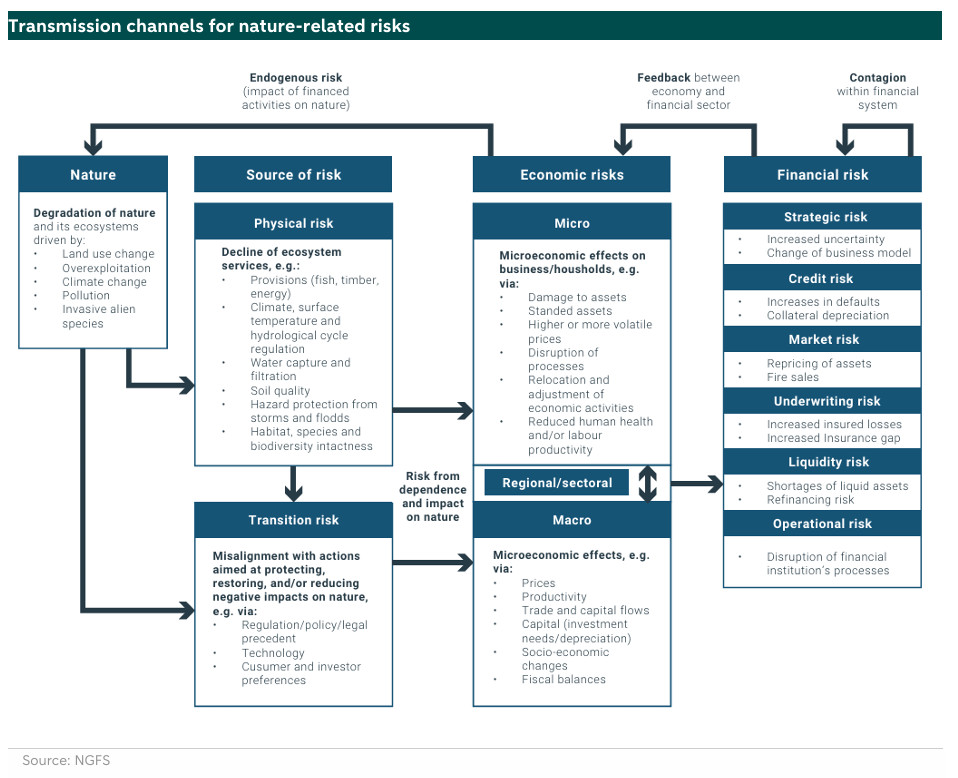

To explore this further, it is important to first understand the types of risks that the loss of nature poses to the economy and, ultimately, to financial institutions. Below, we present the framework developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), which illustrates the pathways through which nature loss impacts micro- and macroeconomic systems, as well as financial institutions.

To demonstrate, let us consider an example of what would constitute a physical risk. Pollinators, such as bees, butterflies, and birds, are essential for crop pollination, which underpins food provisioning. However, their populations are under threat from habitat destruction, pesticide overuse, and climate change. A decline in pollinators would have far-reaching consequences across ecosystems, economies, and the financial system:

1. Disruption of Food Production:

Crops heavily dependent on pollinators—such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and oilseeds (e.g., almonds, apples, coffee, and cocoa)—would experience significant yield reductions.

This would disrupt food chains, causing cascading biodiversity losses as animals that rely on these plants are also affected.

2. Economic Consequences:

Farmers: Lower yields and crop failures would reduce revenues, particularly impacting smallholder farmers in developing countries.

Consumers: Reduced supply would drive up prices for pollinator-dependent crops, making them less affordable and contributing to inflation, particularly for essential and high-value foods.

3. Broader Economic Ripple Effects:

With rising food costs, household budgets would be strained, reducing spending on other goods and services (e.g., fuel), thereby affecting demand in those sectors.

This could result in slower economic growth, with declines in GDP driven by reduced consumption.

4. Financial System Implications:

Farmers and agricultural businesses facing financial stress could default on loans.

This could trigger broader contagion effects, impacting businesses across the supply chain and the banks that financed them, ultimately posing risks to financial stability.

In summary, the loss of nature—exemplified by the decline in pollinators—has the potential to disrupt ecosystems, affect economic activity, and propagate risks to the financial system. While central banks have recognized the dependence of financial portfolios on nature, further research is needed to quantify the materiality and timescales of these risks, allowing financial institutions and policymakers to better prepare for and mitigate such challenges. We will explore these topics in future notes.