ESG Economist - How extreme weather events can make the transition more expensive

In May of this year, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) published a quantification of a set of climate scenarios with a time horizon of 5 years. It was the first time that NGFS elaborated climate scenarios with a shorter time horizon. In this note, we select some useful findings from these NGFS scenarios.

In addition to its regular long-term scenarios, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) this year published a set of climate scenarios with a shorter-term time horizon of 5 years

The transition scenarios in the set show that delays could increase the cost of transition and cause additional financial stress

The physical risk scenarios illustrate that regional extreme weather events can generate temporary but material GDP losses with potential consequences for the world economy

These extreme weather events could delay the transition and increase the cost of it

Transition scenarios affect the creditworthiness of emission-intensive sectors most, while agriculture and other capital-intensive industries are impacted most by physical scenarios

Value added of the shorter time horizon

The NGFS climate scenarios are a well-known starting point for the analysis of the impact of different climate futures. Until last year, these scenario sets ran until 2050, as this has been the point at which Net Zero should be met in a 1.5 ̊C global warming scenario. The short-term scenarios were first published in the form of a in October 2023, and in May of this year the was published. The 5 year time horizon is meant to make it more relevant for policy and planning. Arguably, within a 25-year time horizon the impact of certain shocks would die out before the end of the time horizon, making the impact seem more moderate than it was. This goes in particular for severe weather events, which could have a substantial but largely temporary impact on the economy. Also, long-term scenarios may not reflect fully shorter-term dynamics, such as supply-chain disruptions and financial markets effects.

Modelling of regional compound physical shocks, their global transmission and financial sector feedback loops

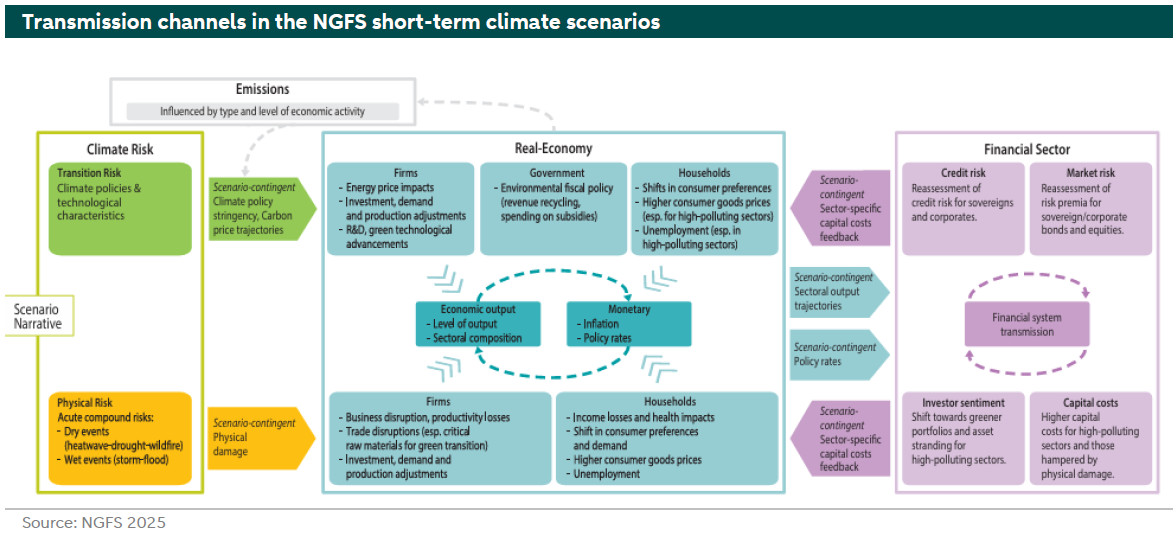

Besides the shorter-term horizon mentioned above, what is the added value of these scenarios compared to the long-term climate scenarios? Firstly, compound physical climate events are modelled. This is important because certain events typically will go together (on the importance of compound risks see f.i. ). The scenarios model a combination of heatwaves, forest fires and droughts (dry events) and a combination of storms and floods (wet events). Secondly, they take the transmission of shocks taking place in one region into other regions and the global economy into account. And lastly, they include financial sector feedback loops, capturing how changes in the cost of capital, financial conditions, and monetary policy responses influence macroeconomic dynamics and financial stability.

Choice of baseline matters

The baseline scenario used is different between the short- and long-term scenarios. Whereas the long-term “reference scenario” is a fictional world with no climate change and no energy transition, the short-term scenarios use a baseline that is similar to a Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) scenario, meaning that each country’s commitments regarding combating climate change is taken into account. The baseline scenario in the NGFS exercise is the NDCs in January 2023. Since then, several significant shifts have taken place, however, such as the reversal of US climate policies, and the introduction of trade tariffs. In this note, we look at the difference from baseline of a certain scenario and not at the absolute levels, limiting the impact of this somewhat outdated baseline, but it should still be noted.

How the different scenarios transmit into the economy

The scenarios are grouped in 4 categories. Firstly, there are two pure transition scenarios. In Highway to Paris (HWTP), a technology-driven and orderly transition unfolds gradually. Carbon tax revenues are reinvested into green subsidies and investments. Although short-term energy prices rise, economic growth from higher investment partly or wholly offsets these impacts. Consumers and investors increasingly favour green sectors, while high-polluting sectors face rising credit risk and capital costs. In the other transition scenario, Sudden Wake-up Call (SWUC), a world of widespread climate unawareness is challenged by a sudden change in policy preferences. Consumer and investor preferences shift abruptly toward green sectors. A sharp surge in carbon prices increases the cost of production, rapidly reducing the profitability of emission-intensive activities and leading to stranding of related assets. The transition occurs too suddenly for markets to adapt, leading to a “Climate Minsky moment” – a wave of financial instability as assets values adjust abruptly.

In the third scenario, Disasters and Policy Stagnation (DaPS), two compound physical events are modelled for each region. Firstly, a combination of droughts, heatwaves and wildfires (dry events) is modelled in 2026. In 2027, a combination of floods and storms (wet events) is modelled. The events have a low probability (of one in fifty), but a severe impact. The scenario has six regional versions, where each assumes the events occur in the given region and subsequently affect the global economy through financial and trade linkages.

The final scenario, Diverging Realities (DiRe) is a scenario combining physical and transition risk. In the DiRe scenario, physical events are modelled to occur in a different way than in DaPS. The compound dry events are modelled to occur in Asia, South America, and Africa in 2025, 2026, and 2027 respectively. The compound wet events are modelled to occur in Asia, South America, and Africa in 2028, 2029, and 2030 respectively. The events are less severe than in DaPS and their probability is somewhat higher (one in twenty). Still, like in DaPS, they affect the global economy through financial and trade linkages. At the same time in this scenario, advanced economies follow transition pathways aligned with HWTP, leading to a global emissions reduction that falls short of Net Zero targets.

Scenario results

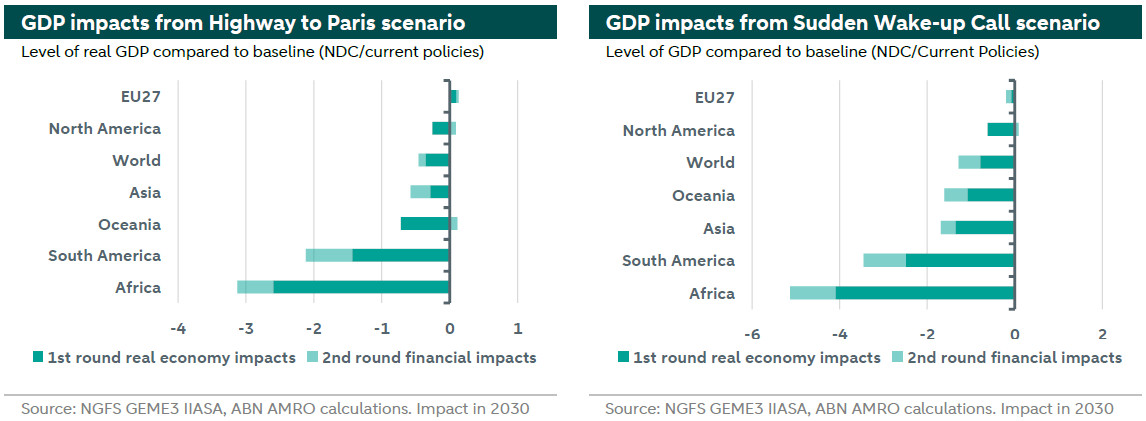

In the charts below, the impact on GDP of the scenarios via the transmission mechanisms (shown in the picture above) is visible. The impact is split between the first-round real economy impact and second-round financial feedback loops (shown in the picture by the purple arrows). The results show that the impact from transition scenarios, even if the transition is disorderly, is smaller than that of the physical risk scenarios even in this short-term horizon. However, it should be considered that, as these physical risk scenarios take into account a specific sequence of compound events in 2026 and 2027, the impact is more transitory. The results also show that even in this relatively short 5-year time horizon, the impact from a timely, orderly transition is substantially more favourable than that of a delayed, abrupt transition. The difference is mainly caused by two factors: (i) abrupt, uncoordinated and delayed policy shifts and (ii) insufficient government investment in green innovation and technologies increasing the economic costs of transition.

The overall impact of the transition scenarios is relatively muted, especially in Europe, at around zero for both HWTP and SWUC. This can probably be explained by the fact that the additional carbon price shock is more limited as the region’s baseline carbon pathway is already more ambitious than in other regions. In the same vein, the larger impact of the transition scenarios in Africa (-3% for HWTP and -5% for SWUC) and South America (-2% for HWTP and -3% for SWUC) can be explained. The NDC baseline in these regions includes a lower carbon price, so that the gap between the baseline and the transition scenarios is larger.

The physical risk scenarios demonstrate that regional extreme weather events generate material losses through destruction of infrastructure, decreasing investment, and spiking unemployment, through capital destruction, output loss, and labour productivity loss. Droughts induce a reduction of output in sectors that are exposed to water risk, such as agriculture. Heatwaves induce a reduction in labour supply and productivity for sectors with outdoor and physically intensive activities. Wildfires induce destruction of capital stocks and business interruption. Storms and floods cause capital destruction and business interruption through, among others, that capital destruction.

In the EU-specific version of DaPS, in which a severe compound physical risk scenario takes place in the EU, the region stands to lose almost 5% of GDP, with almost half of it second-round feedback through uncertainty shocks increasing risk premia and costs of capital. By contrast, the impact of this scenario for (a region-specific compound event in) Africa is around 12% of GDP, with the large majority being a first-round real economy impact. In DiRe, the impact of the combined transition and physical risk scenario, in which the EU still advances on the transition, is around -2% in 2030. It should be noted, however, that the DaPS and DiRe results cannot be directly compared as in DiRe, the physical impact comes from physical events in other regions, whereas in DaPs (EU variant) the physical event takes place in the EU itself.

With regards to prices, the scenarios show that inflation behaves differently depending on whether the scenario involves transition, or physical risks. In transition scenarios, inflation is primarily driven by supply-side factors. The introduction of higher carbon taxes increases energy and production costs, which feed through to a higher overall price level. The increase is gradual in Highway to Paris and Diverging Realities (for DiRe, the orderly nature of the transition obviously only goes for the regions in which there is transition taking place in this scenario). Central banks respond to these developments with gradual interest rate hikes to manage inflationary pressures. Conversely, the "Sudden Wake-Up Call" scenario sees the abrupt implementation of a high carbon price, resulting in a sharp and sudden inflationary spike. In the physical risk scenarios, natural hazards initially lead to a short-run rise in inflation due to disruptions in production in the regions affected by extreme weather events. Deflationary episodes follow due to a sluggish output recovery

Diverging Realities: how physical risk can increase the cost of transition

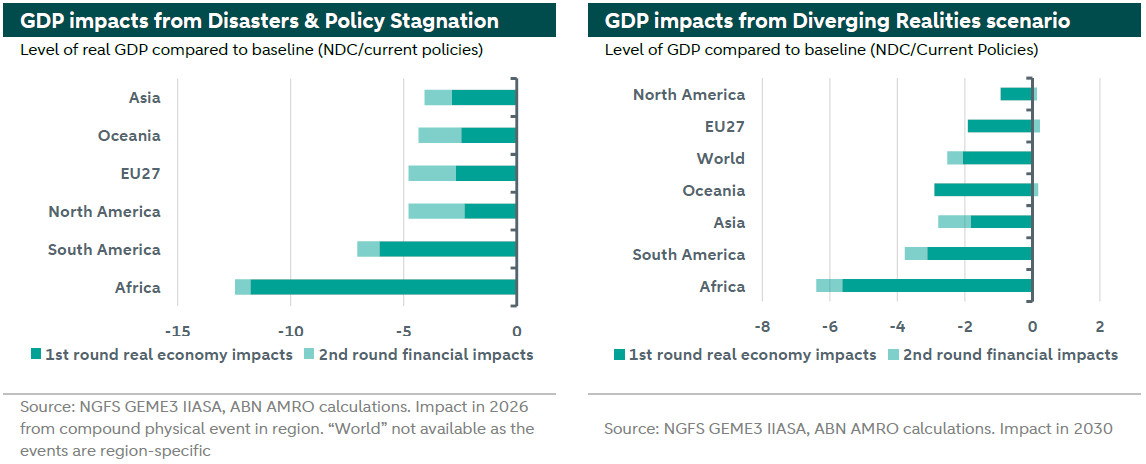

So how is the EU impacted by physical impacts in other regions in the Diverging Realities scenario? The DiRe scenario models that intensifying climate hazards in some regions will lead to less production of green energy equipment, disruptions in import and exports and resulting shortages in the supply of critical minerals needed for the successful green transition in advanced economies. In this scenario, Africa, South America and Asia suffer the strongest economic shocks, being directly affected by a wave of adverse weather events, combined with global effects of disasters elsewhere. These shortages then induce supply-chain disruptions, which inflate transition costs, compared to a scenario without physical risks. In this scenario, the production of green energy equipment is particularly hampered, standing at about half the levels of the pure transition scenarios (see below left chart). Goods particularly affected by supply chain interruptions are solar panels, equipment for wind power, and batteries. Global trade is also at lower levels when compared to transition scenarios, with particularly negative effects on green transition equipment, due to the supply chain interruptions. This scenario illustrates that physical events can increase the cost of transition, already in the short term.

Financial feedback loops

As mentioned before, the scenarios include financial feedback loops. The real economy impact of the scenario on the real economy influences the capital costs of different sectors, and these sector-specific capital costs have a second-round impact on the real economy. In extreme weather scenarios, the sectors most affected by a physical event through financial feedback loops would be agricultural and capital-intensive ones (please see right-hand chart above). Heatwaves, wildfire, droughts, lead to a considerable increase in capital costs and default probabilities from the agricultural sector globally. Floods & storms increase financial risk more strongly for the transport sector, power supply and consumer sectors. Capital-intensive green sectors are also hit by extreme weather. In transition risk scenarios, the capital costs would increase in high-emission sectors, as credit risk is impacted by higher carbon costs and investors adapting their expectations for these sectors. The green sectors benefit from lower capital costs in those scenarios due to investor expectations improving. In addition, in HWTP green subsidies lead to a reduction of capital costs to green sectors.

Conclusion

Concluding, the NGFS short-term climate scenarios provide valuable insights into the economic and financial impacts of various climate futures within a 5-year horizon. These scenarios emphasize the importance of timely and orderly transitions to mitigate adverse outcomes compared to delayed or abrupt policy shifts. The modelling of compound physical climate events, their global transmission, and financial feedback loops highlights the complex dynamics of climate risks on economic stability. Additionally, the findings illustrate how physical risks can exacerbate the costs of green transitions, particularly through supply chain disruptions and shortages in critical minerals and equipment.