ESG Economist - Economic impact of carbon price sensitive to how revenue is spent

Carbon pricing is the main economic policy driver of the speed of transition in climate scenarios. By making emitting carbon more costly, it provides a financial incentive to decarbonise. However, it also has effects on the general economy. By putting a price on something that was previously cheaper or free, inflation can increase. Depending on whether or not the costs are passed on to consumers, it affects either purchasing power of households, or profitability of companies. This carbon pricing can take the form of an actual government-revenue generating price, such as is the case in cap-and-trade systems (such as the EU ETS), or carbon taxes. It can also take the form of other measures that discourage emitting carbon, such as policies limiting emissions or strict rules (“shadow price of carbon”). In the case of carbon pricing that generates government revenue, the economic impact varies depending on how these carbon revenues are used. In this note we look into the economic impact of different uses of carbon revenues.

Carbon pricing is the main economic policy driver of the transition, providing a financial incentive to decarbonise

The macroeconomic impact of carbon pricing depends among others on how carbon revenues are used

Governments have various options to spend this income, which will have different implications for economic growth

Model outcomes seem to suggest that when looking at headline GDP, recycling carbon revenues through public investment leads to the most favourable outcome

Government-revenue generating carbon pricing

A large group of countries and regions have introduced some form of carbon emission trading system or carbon tax (see ), which generate government revenues. Currently these are generally moderate, though they have the potential to be substantial if carbon prices/taxes rise from current levels – as they would need to in Net Zero scenarios. One important example of carbon pricing is the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) which generated EUR 38.8 bn in 2022 (equal to around 0.2% of 2022 nominal GDP) according to the European Environment Agency (EEA; ). Around 77% of this income was directly transmitted to EU Member States. According to EU regulation () member states have to spend all ETS income on climate-related purposes. These climate-related purposes include government investment in for instance technology for renewable energy development, improving energy efficiency or transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Part of the income may also be used to give financial support to lower and middle-income households to compensate for climate-related income deterioration. For instance, via income transfers or tax cuts. These different uses of carbon revenue have different impacts on GDP growth.

GDP impact of Net Zero is sensitive to how revenues are used

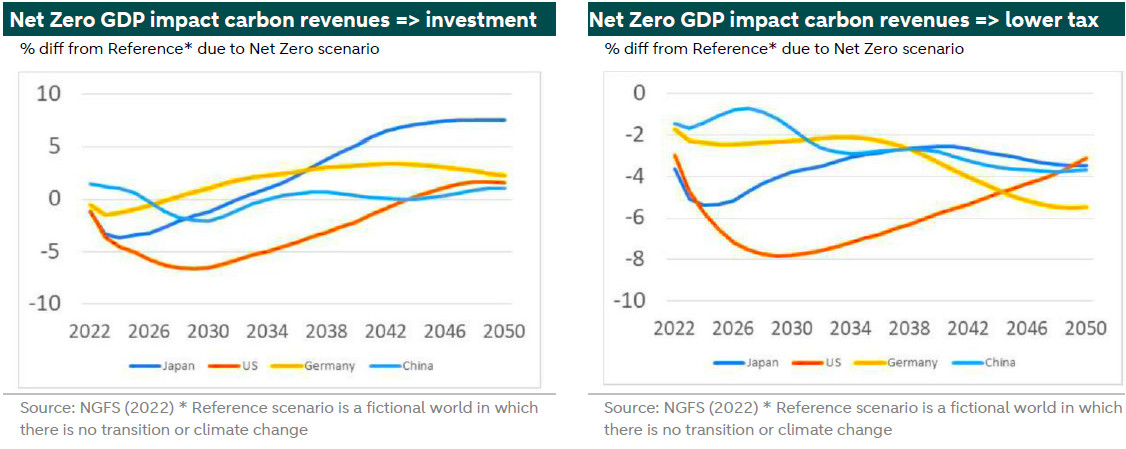

The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) has published an analysis in which it looks at economic impact of climate scenarios and the sensitivity of those results to the underlying economic assumptions (). Among others, it looks at the sensitivity to assumptions regarding the use of fiscal revenues that arise as a result of carbon pricing. It finds, among others, that different ways of carbon tax revenue recycling have different impact on the economic variables. This analysis, which is done in the NIGEM model (the economic model used for the NGFS climate scenarios), considers a number of different options in which carbon revenues are recycled. For this note, we disregard one of these options, namely that revenues are used to pay down government debt, as this is not in line with EU regulation. This leaves, firstly, the option of reducing general taxes by the same amount as the carbon revenues, or equivalently, increase transfers to households by the same amount. And secondly, using carbon revenues to increase public investment. To compare these two options, two versions of the Net Zero scenario are created in NIGEM, one in which the revenues are recycled through lower taxes, and one in which the carbon revenues are used for government investments. GDP impacts for a number of selected countries are shown in the charts below.

This exercise shows that in a Net Zero scenario, recycling through public investment brings the strongest stimulus to economic activity. There are even positive impacts on GDP for Germany and Japan for this variation of the Net Zero scenario.

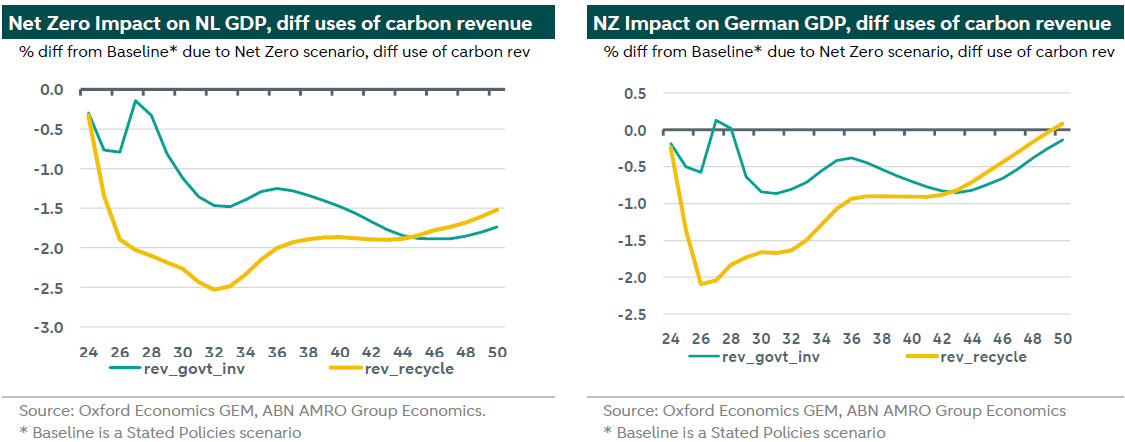

We have tried to corroborate this result in the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model (GEM). In the charts below, we make 2 alternative versions of the Net Zero scenario: one in which carbon revenues are wholly recycled back to disposable income (rev_recycle) and one in which carbon revenues are used for government investment (rev_govt_inv). We have done this for Net Zero scenarios for the Netherlands and Germany. Please note that it is not straightforward to compare the size of the impacts, due to different assumptions and modelling and the use of a significantly different baseline in the two modelling environments.

As the two graphs above illustrate, the Net Zero scenario has a small negative impact of GDP generally, no matter how the carbon revenues are used, due to the impact of carbon pricing on the economy. However, the results from this exercise in the Oxford Economics GEM model indicate that using carbon revenue for investment provides the best outcome (when looking at headline GDP alone). All in all, the exercise corroborates the finding in the NGFS sensitivity analysis paper, that using these funds for (green) investment reduces the negative impact on GDP most.

GDP impact is less negative when carbon revenues are used for investment …

As shown above, both the results of the NGFS sensitivity analysis and the Oxford Economics GEM model suggest that, when looking only at the impact on headline GDP, the most favorable outcome would result from using the extra income from carbon pricing for government investment instead of income transfers to households (i.e. the fiscal multiplier of government investment is higher than that of an income transfer to households). Although compensating households would limit the damage to private consumption from higher carbon prices and inflation in the short term, the upward impact on total GDP growth would be moderated by the fact that households probably will save part of the extra income. Indeed, in 2023 households saved more than 14% of disposable income. On top of that, part of consumer spending will be on imported goods, which also reduces the impact on EU GDP, whereas governments can actively chose to spend locally. The recently adopted Net-Zero Industry Act (), which sets a target for the EU to produce 40% of its annual deployment needs in net-zero technologies by 2030, should support intra-EU investment by governments, which could raise the impact of extra government investment on EU GDP growth.

… with investment in environmental protection having an above-average multiplier

According to a 2021 IMF Working Paper WP/21/118 (), there will be a large and significant impact on GDP following increases in public investment. A shock to public investment equal to one percent of GDP has an estimated multiplier equal to 1.3 in the short term (i.e. GDP rises by 1.3 percent on impact) and of 2.0 percent after one year. The paper also estimates the impact of public investment per sector and finds that the multiplier of investment in environmental protection is higher than the aggregate, at 2.7 percent in the short term and 2.9 percent after one year.