ESG Economist - Europe leads climate race, but march to net zero is far from won

To achieve a real acceleration in decarbonisation, both energy production and consumption must switch to renewable and low-carbon energy sources at an accelerated pace. However, this process is still slow and faces some persistent obstacles, including grid congestion, staff shortages, financing challenges, and the often complex and volatile regulations in many countries. Despite the scaling back and reversal of climate policy in many countries – led by the United States (US) – the European Union (EU) remains committed to achieving climate neutrality by 2050, as laid down in the European Climate Law. This further increases the differences in decarbonisation paths between countries/regions and pushes climate targets further out of reach. In this analysis, we examine the current state of play in these decarbonisation paths of the most important countries worldwide and of the EU-27 in particular. What are the trends in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of countries and what differences are visible? What goals are the largest GHG-emitting countries pursuing with their climate policies and where does the EU-27 stand in this regard? How does final energy consumption (fossil fuel share) relate to GHG emissions and the trend in energy efficiency? And is the pace of GHG emission reduction (post-Paris Agreement) sufficient to ultimately achieve the EU's climate targets? We end this analysis with a conclusion.

Having a decarbonisation strategy offers many advantages for companies, provided that existing obstacles are addressed

The global decarbonisation trend remains disappointing, with GHG emissions increasing by 10% over the past decade

However, the carbon intensity of electricity production has decreased by 9% globally in the post-Paris Agreement period

The progress made by the EU in decarbonisation is promising

This shows that implementing ambitious climate goals can have impact

The EU is a leader in decarbonisation, with a 19% reduction in emissions between 2017 and 2024, significantly more than other countries

Despite progress, the EU remains dependent on fossil fuels: in 2024, more than 50% of the energy mix consisted of fossil fuels

Deeper investments in technology and infrastructure are necessary to achieve climate goals

The challenges are considerable and are exacerbated by many geopolitical obstacles, but they further emphasize the need for a joint and transparent approach within Europe

Decarbonisation remains relevant

Accelerating decarbonisation has five main advantages. It brings energy and carbon savings (1) and, at the same time, cost savings (2). For example, an energy efficiency measure can significantly reduce the energy and fuel consumption of many processes. In addition, decarbonisation brings multiple environmental benefits (3), such as water savings, savings in raw materials and resources, and improved air quality. Furthermore, decarbonisation is a way for companies to specialize, thereby further strengthening or expanding their competitive advantage (4). Finally, low-carbon ambitions in one sector have an impact on other sectors (5). For example, ammonia—produced in the chemical industry—is widely used in the production of fertilizers, which are in turn used in agriculture. Decarbonizing ammonia production therefore also has a positive impact on making agriculture carbon-free.

A study published in the International Review of Financial Analysis (Ibishova, Misund, Tveterås, November 2024, see ) showed that companies see visible improvements in financial performance as soon as they intensify their efforts to reduce CO2 emissions. A study by the University of Groningen (see ) showed that when greenhouse gas emissions decrease, companies' profitability ultimately increases. From these reports we can learn that companies with low emissions generally have higher revenue growth, are more resilient to negative shocks in the sector—particularly due to a more loyal customer base—have lower operating costs (greater efficiency), and also have lower capital costs (less risk). Decarbonisation therefore remains relevant. However, despite these advantages of decarbonisation, it appears that the acceleration in decarbonisation has not yet reached the desired level globally.

The global decarbonisation trend is still disappointing

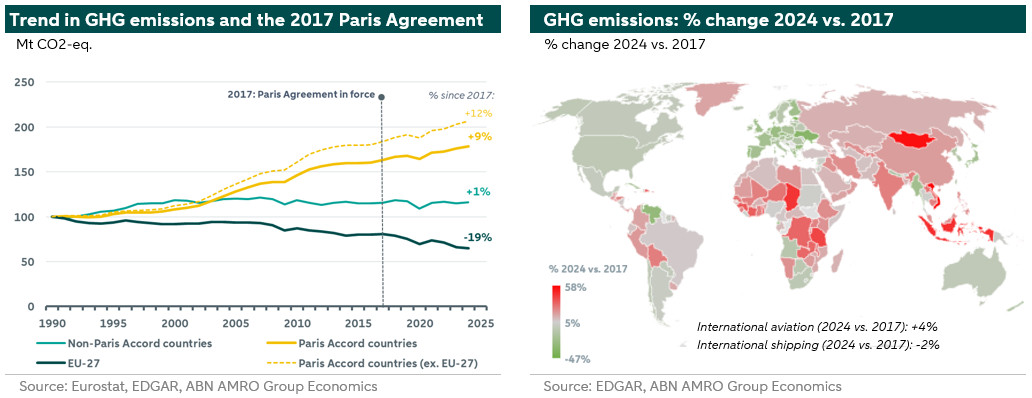

Global GHG emissions have increased by 10% over the past ten years (2014-2024). This is less than half the increase over the previous ten-year period. In 2004-2014, the increase in GHG emissions from all countries combined was still 23%. This indicates that more ambitious climate policies by countries are having an effect, with the EU's climate policy in particular having had a major impact.

The EU has ambitious climate goals. For example, the European Climate Law sets a binding target of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 and reducing net GHG emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. Pursuing these goals has clearly made the EU a pioneer in decarbonisation. Between 2017 and 2024, GHG emissions in the EU fell by 19%. The difference with other countries is considerable. In many countries in Asia and Africa, GHG emissions actually increased between 2017 and 2024. The most striking feature of the figure on the left above is that GHG emissions in countries that have not signed the Paris Agreement – including the US – have increased much less than in countries that are party to the agreement. But this is mainly due to trends in the US. The other non-Paris Agreement countries – many of which are in Africa, but also include Iraq, Iran, and Turkey – saw their GHG emissions increase by 15% in the period 2017-2024. In the US, emissions decreased by 4% in the same period.

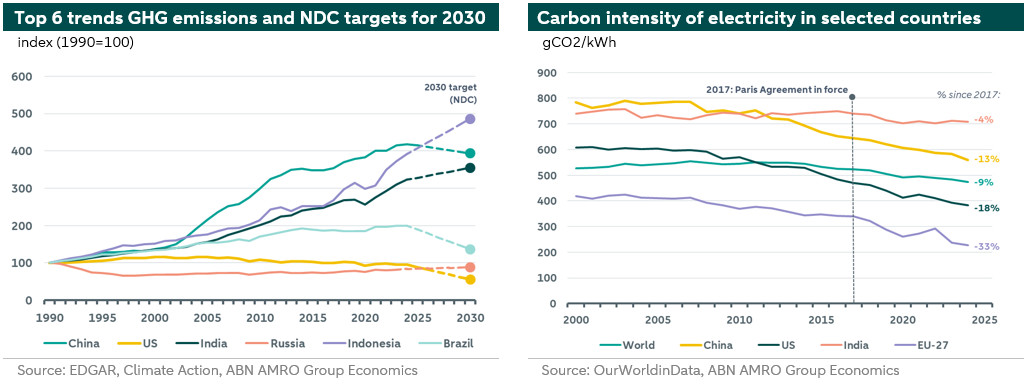

While the Paris Agreement sets joint global emission targets, the so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of individual countries form the backbone for ultimately achieving those targets. The NDCs reflect each country's intended efforts to reduce its own emissions and adapt to the effects of climate change, including a description of its decarbonisation strategy with implementation and timelines. According to these schedules—see the figure on the left below showing the top six largest GHG emitters in the world—countries such as India and Indonesia will not reach their peak GHG emission levels before 2030, while China, the US, and Brazil intend to pursue a decline in emissions through 2030.

The fact that absolute GHG emissions in some countries have not yet reached their peak does not mean that decarbonisation is not taking place in these countries. The figure on the right below shows that steps have indeed been taken to reduce GHG emissions, particularly in the energy sector. For example, India has not yet reached its peak level, but the carbon intensity of electricity production has decreased by 4% over the past seven years. These are small steps, but on balance it is a positive trend.

Decarbonising electricity production is essential for decarbonising the entire energy sector. The carbon intensity of electricity production has decreased by 9% globally in the post-Paris Agreement period. Here too, the EU is a frontrunner, with a 33% decrease in carbon intensity in the period 2017-2024.

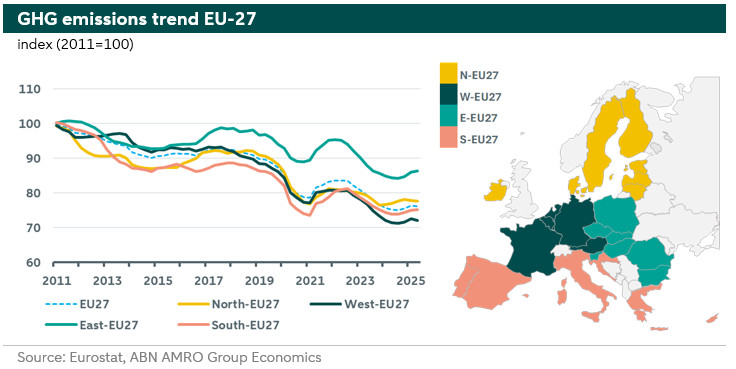

The EU-27 decarbonisation trend is more positive

The EU is on the right track by moving away from fossil fuels at a faster pace. The decline in GHG emissions is mainly due to the sharp reduction in emissions from the energy sector. This is reflected in the trend in GHG emissions in all regions of the EU. However, the pace of GHG emission reductions in Eastern Europe lags behind the rest of the EU. The use of the most emission-intensive fuels, such as coal and oil, has fallen sharply in many EU countries, while at the same time the growth of renewable energy has accelerated throughout Europe. The EU has set itself the target of using at least 42.5% renewable energy by 2030. Although it is doubtful whether this target will be achieved, the growth in renewable energy is set to continue for the time being.

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) has also made a major contribution to reducing GHG emissions. The EU ETS is forcing the largest emitters of greenhouse gases in the energy supply and industrial sectors in Europe to accelerate their decarbonisation. By reducing each year the number of free emission allowances – which are included in the system – greenhouse gas emissions in the business sector will decline at an accelerated rate, which in turn will contribute to efforts to achieve the climate targets for 2030 and 2050.

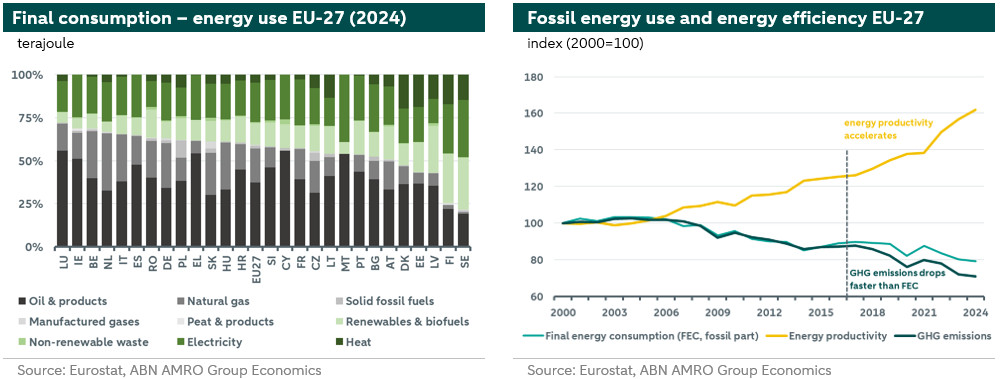

The EU is still largely dependent on fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. The 2024 energy mix shows that most countries in the EU still depend on these fossil fuels for more than 50% of their energy supply. According to energy think tank EMBER, the EU's dependence on fossil fuel imports can be reduced more quickly. This can be achieved, among other things, by focusing on electricity generation from domestic sources in the electricity supply and by making optimal use of electrical technologies in the EU energy system. If implemented correctly, this could result in a 50% reduction in imports by 2040.

The results achieved by the EU in the field of energy efficiency have also been positive in the post-Paris period. Energy productivity has increased at an accelerated rate, while GHG emissions have continued to fall. This decline has been even faster than that of the fossil fuel share in final energy consumption (FEC). This means that the increase in energy efficiency in the EU has made a major contribution to the reduction in GHG emissions. This is a positive result for the EU as a whole, but there are significant differences between EU countries. This is because energy intensity in some EU countries is still worryingly high and not easy to reduce due to their considerable dependence on fossil fuels.

EU climate policy and its 2030 target encourage decarbonisation

Since 1990, the Baltic States, but also Romania, and Bulgaria have reduced their GHG emissions in relative terms by far the most of all EU-27 countries. These countries have now achieved the 2030 target. However, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Romanian economy is still very emission- and energy-intensive due to its heavy dependence on fossil fuels. This is particularly evident in the high intensity of fossil fuels in the transport sector and the low energy efficiency in the built environment.

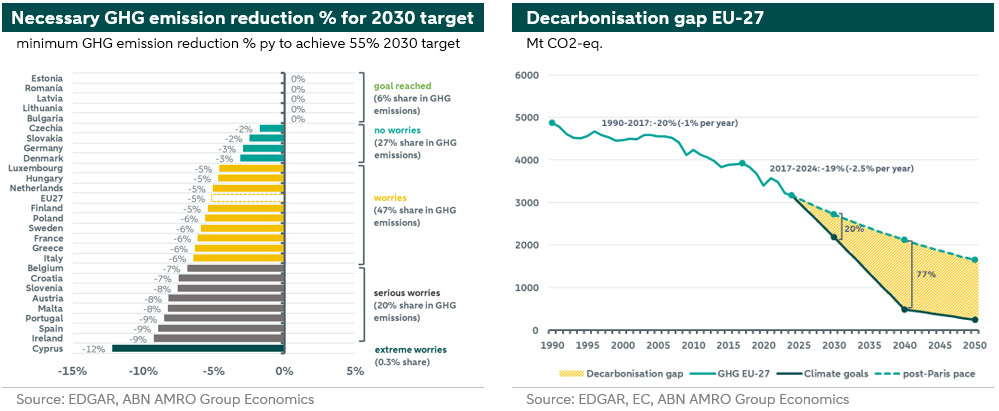

The Czech Republic, Slovakia, Germany, and Denmark do not seem to have anything to worry about. These countries—which together account for 27% of total GHG emissions in the EU-27—will be able to achieve the 2030 target if they manage to maintain the GHG reduction rate seen in the period 2017-2024. In the other EU-27 countries, concerns about the feasibility of the 2030 target are greater. For the countries with a combined share of 47% of total EU emissions – the yellow bars in the figure on the left below – concerns remain about the feasibility of the 2030 target. For more than 20% of EU emissions, much greater concerns remain. Each country faces its own individual challenges in this regard.

The climate targets are not yet within reach. In order to achieve the target set for 2030, it is necessary to deploy the decarbonisation technologies with the greatest impact on a larger scale. This requires substantial investment and a stronger expansion of network capacity for further electrification, supplemented by stimulating sustainable government policy. The efforts currently being made will help to make the transition to climate neutrality for the EU towards 2050 somewhat smooth and affordable. At present, the outlook for the feasibility of the transition is still relatively unfavorable. Much remains to be done. The challenges – such as the obstacles to the energy transition and the changing geopolitical context – still require a great deal of attention and are slowing down the transition.

But despite the challenges, the EU-27 has made progress in reducing greenhouse gases. In the period 2017-2024 (the post-Paris Agreement period), a clear acceleration is visible compared to the period 1990-2016. This is a trend that can be maintained in the coming years with existing decarbonisation technologies. The key now is to accelerate the reduction in emissions and the further transition, because with the rate of emission reduction achieved in the post-Paris Agreement period, the climate targets are still out of reach. If we continue at this pace towards 2030, there will be a decarbonisation gap of 20%. This gap—the difference between the 2030 climate target and what is achievable with the reduction rate in the post-Paris Agreement period—will only widen further towards 2050 if no additional measures are taken to reduce GHG emissions. More transparent policies and cooperation on the European continent will help to stimulate the transition to climate neutrality in this regard.

To achieve the 2030 target, EU countries must continue to invest more in environmentally friendly technologies, decarbonise the energy sector, make buildings more energy efficient, and promote cleaner forms of transport. EU emissions figures show that decarbonizing transport and buildings is proving particularly difficult. More restrictive policies in the coming years will help these sectors reduce GHG emissions at a faster pace. While large emitters in the energy and heavy industry sectors are covered by the Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the transport and buildings sectors (as well as agriculture and industrial companies not covered by ETS-1) are subject to joint annual limits on GHG emissions under the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) via ETS-2. This helps to keep the climate targets for the entire economy within reach.

Conclusion

Despite increased investment in clean energy and decarbonisation technologies (and innovation in this area) in recent years, it is still insufficient to structurally increase the pace of GHG emission reductions. This is partly due to the preconditions for achieving further acceleration in emission reductions, such as the structural shortage of personnel, the limited network capacity for electrification, and the uncertainty surrounding the supply of raw materials. In addition, transparent, supportive, and stimulating government policy remains indispensable to keep the course toward a climate-neutral economy in sight. However, it also requires greater efforts from EU companies across the economy. Our analysis shows that many more climate measures and investments in decarbonisation are needed to achieve the EU's climate goals. Not only in the technologies themselves, but also in infrastructure, for example.

The progress made by the EU in the field of decarbonisation is promising and shows that ambitious climate targets can have a real impact. Nevertheless, it is clear that the current pace of emissions reduction is insufficient to fully achieve the targets set for 2030 and 2050. This points to an urgent need to intensify efforts, including by further investing in clean technologies, accelerating the energy transition, and addressing sectors that are lagging behind, such as transport and buildings. The challenges are considerable and are exacerbated by geopolitical obstacles, but they further emphasize the need for a joint and transparent approach within Europe. Only by closing the gap between ambition and reality can the EU continue to play a leading role in the global fight against climate change and build a future that is truly climate neutral.