ESG Economist - Increasing our security could come at an environmental cost

As geopolitical fears mount, EU countries are discussing options to ramp up defence spending. Currently, there are three options: finance it with debt, raise taxes and/or cut spending elsewhere, or use EU programmes.

Climate spending might be vulnerable to cuts as funds are reallocated towards defence spending

Moreover, increasing defence spending is also closely linked to a ramp up in Europe’s scope 1 and 2 emissions

Military operations primarily rely on fossil fuels, leading to significant environmental impacts despite potential electrification efforts

The emission intensity of the defence sector is two to three times greater than that of other economic activities

This means that when military numbers rise due to transfers of personnel from other parts of the economy, emissions also increase

Efforts to reduce emissions have been largely unsuccessful, with increased military spending predicted to raise emissions further

As geopolitical fears mount, EU spending on defence is also expected to increase. In fact, defence spending has been on top of government agendas as they feel less certain about support from the US. As we highlight in a previous note, “this has given Europe a reality check that it needs to stand more on its own feet in terms of defending its own borders” (see here). However, Europe’s financial resources are limited, and therefore increasing defence spending will come at the expense of either building up more debt, raising taxes or decreasing spending in other areas, which could include climate. In addition, re-directing funds from EU programmes could have the same result. In this note, our aim is to understand how an increase in defence spending could impact climate investments for European countries. Furthermore, we also look at the emissions that might result from an increase in defence spending.

How can European countries increase defence spending?

European countries can increase defence spending in four different ways, with different possible impacts on the climate budget. Below, we explore the different options and we assess their potential impact on climate spending.

1. Increase deficits/debt

The primary method for a sovereign to increase new spending is through debt financing. However, European countries must adhere to EU fiscal rules, which mandate maintaining budget deficits below 3 percent of GDP and keeping gross government debt under 60 percent of GDP. Recently, the European Commission proposed the activation of the “national escape clause” , which allows countries to deviate – on grounds of higher defence expenditure – from the net expenditure paths set out in their medium-term fiscal-structural plans or from their corrective path under the excessive deficit procedure (EDP). There is now flexibility for such additional spending on defence, up to a limit of 1.5 percentage points of GDP per year over 2025-28 compared with existing fiscal commitments, in countries that request the activation of the national escape clause.

Although this provides extra spending capacity for all countries, heavily indebted countries like France or Italy must be cautious about this additional expenditure and consider how it might be perceived by investors and the market at large. Conversely, for countries like the Netherlands or Germany, securing funds for security purposes is relatively straightforward. For instance, German lawmakers have recently approved a huge increase in defence and infrastructure spending, exempting this expenditure from Germany’s strict debt rules, and creating a EUR 500bn infrastructure fund, which also includes increased climate investments .

With regards to its impact on climate spending, we do not foresee any direct impact from increasing budget deficits to boost defence spending, given that climate spending would, in principle, not be affected.

2. Raise taxes and/or cut other spending

This approach represents another traditional method of encouraging countries to increase defence spending. By adopting this strategy, countries would aim to avoid further increasing budget deficits and, consequently, from increasing public debt and borrowing costs, while still stepping up defence expenditures. However, raising taxes is generally unpopular among the public, so cutting spending becomes the more viable solution. Some sectors may be more susceptible to budget reductions than others, depending on their perceived importance or relevance or how quickly it is noticeable to the public. For instance, climate spending could be one of the sectors more likely to face cuts, especially when compared to sectors such as health or education.

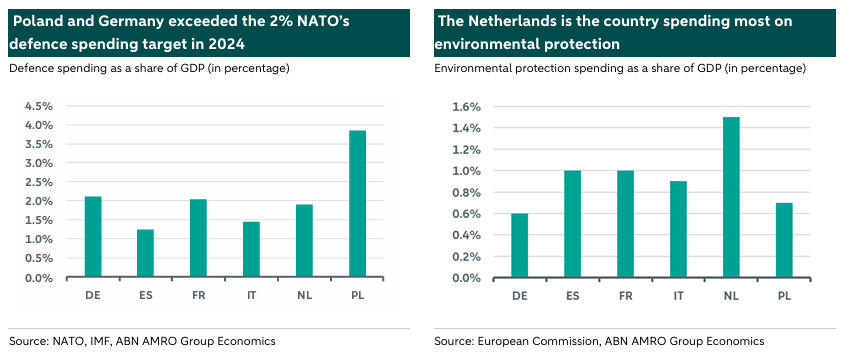

Below, we plot both defence and environmental protection spending for the EU-27's largest six countries (Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Poland) as a share of real GDP. We derived these estimates from European Commission’s data on the share of GDP spent on environmental protection in 2023. According to EC, environmental protection includes “measures to control or prevent the emission of greenhouse gases”.

Many EU-27 nations are still not meeting NATO's defence spending target of 2%, with Spain and Italy standing out as significant examples among the larger countries. Regarding climate action, most countries are allocating less than 1% of their GDP to environmental protection measures, with the Netherlands being a leader in climate-related expenditure, allocating 1.5% of its GDP to the sector. On average, European countries are currently dedicating around 0.5% of their GDP to climate efforts, which is considerably below the investment needed to achieve net zero by 2050. This budget could nevertheless be viewed as an opportunity to reallocate resources to meet NATO's 2% target and, in some cases, could potentially be enough to achieve it. Given recent EU initiatives to postpone the 2040 climate targets (see here) and the current legislative atmosphere, where the European Commission seems to be tempering its ambitions (see here), there may be a perceived incentive for countries to temporarily shift funds away from climate spending. This shift could be seen as less urgent compared to pressing geopolitical issues. However, this approach might negatively impact countries' investments in climate initiatives, which would have detrimental effects on the environment and Europe's goal of achieving net zero emissions.

Finally, it is important to note that this is merely a hypothesis, and increasing defence expenditures may not necessarily impact climate spending. Interestingly, recent developments suggest that Spain is actually contemplating a different approach. According to Bloomberg (), Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has announced that 17% of this year’s EUR 23 billion military spending will be allocated to natural disaster relief. This makes Spain the first European country to explicitly dedicate a significant portion of its new military expenditure to climate resilience programmes.

3. Make use of the current EU programmes

As mentioned in our previous note (see here), some European politicians have suggested utilizing existing EU programmes to partially boost defence spending. The proposal involves redirecting portions of existing funds toward defence-related investments. For example, the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme, which is currently active and represents the largest financing pool in the EU, which amounts to nearly EUR 800 billion in total, could be such a source. Currently, only EUR 300 billion has been disbursed from the EUR 640 billion allocated to member states, with an additional EUR 100 billion remaining to be distributed among all member states. Concerning its impact on climate initiatives, while the already allocated funds are not anticipated to be revoked or cancelled, there exists an opportunity cost in directing the remaining undistributed funds toward defence instead of climate efforts. This is particularly significant because the NGEU funds were initially intended to make “economies and societies more sustainable, resilient and prepared for the green and digital transitions”. Ultimately, this could further postpone the transition to a net-zero economy. Nevertheless, redirecting the undistributed funds toward defence spending would require unanimous approval from EU member states, alongside potential legal and political reforms to the existing NGEU framework. As such, this option presents itself as a complex challenge that might take time.

Additionally, other European defence facilities, such as the European Defence Fund (EDF), the European Defence Industry Program (EDIP), and the European Peace Facility (EPF), can also function as financing tools. Regarding these facilities, we do not anticipate any impact on climate financing from using these funds for defence investments. These defence tools would not have been utilized to fund climate initiatives, and therefore, there is no associated opportunity cost.

4. New EU programme

Another option is to create a new EU defence fund programme. The idea would be to issue EU debt, similar to what was done with the NGEU post-covid recovery instrument. Such an approach could release national budgetary resources and provide long-term funding stability, while strengthening the domestic defence industry. To address potential moral hazard, modifications could be made so that countries currently not meeting NATO targets, like Italy and Spain, must first achieve the 2% target before accessing this financing pool. As a consequence, and consistently with the impact of the first option, countries would still need to reallocate spending across ministries, with the climate sector potentially being one of the most vulnerable to these shifts. However, the programme would limit such shifts for spending above the 2% target.

Although the new EU programme itself would not directly affect climate-related investments, the conditions for accessing EU funds might influence climate spending. Nonetheless, the idea of joint debt remains politically sensitive, particularly among the most fiscally conservative countries in Northern Europe. As a result, this option may not be the quickest or easiest to implement at this time.

Strong impact of military activities on the environment

According to calculations by consultancy firm Roland Berger (), global defence activities account for a combined share of 1-1.5% of total global emissions. However, given the sensitive nature of military activities, there is often a lack of transparent and accurate data in many of these areas. For instance, the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS) suggests a higher figure of about 5.5% for the combined emissions of all armed forces worldwide.. According to calculations by NATO, the combined NATO defence activities of 32 countries emitted 236,510 kt of CO2 equivalents in 2023. This represents a share of approximately 0.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This means that if NATO's armed forces were to form a single country, they would rank around 30th among the world's largest polluters. Moreover, Roland Berger’s study noted that, on average (on a global basis), the air force is responsible for around 20-25% of defence emissions, the navy for 30-35% and the army for another 30-35%, with the rest coming from other branches of the military.

The impact of military activities on the environment is therefore relatively large and can occur through various channels. This can be through increasing energy consumption due to the growing logistical movements of existing military personnel and equipment. In the current geopolitical climate, military training and exercises take place more frequently and on a larger scale. This requires more fossil fuels, for example for vehicles, ships, missiles and aircrafts. In addition, increasing research and development activities related to defence also have a negative impact on the environment on balance, although they only account for a small share. A larger share can be attributed to an expansion of military personnel, an increase in the production of military equipment and the construction of military infrastructure, including the maintenance of equipment and infrastructure. Military equipment encompasses all processes in the value chain, from the extraction and processing of raw materials to manufacturing and logistics, in order to deliver the end product.

All-in-all, the consumption of fossil fuels is the main source of greenhouse gas emissions in the military sector. The electrification of military operations is certainly possible in some areas, but for energy security, the defence sector will remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels for the time being. This means that any further intensification of military activities in a country will have a negative impact on the environment. In order to bring military emissions down, the consumption of fossil fuels must be reduced. This can be achieved, for example, by switching to sustainable fuels, ensuring greater efficiency in both fuel consumption and operational activities, and using more sustainable energy sources for buildings, military facilities and logistics processes. Transport and equipment used in military operations and exercises typically account for 65-75% of total energy consumption. The vast majority of this is aviation fuel. However, alternative fuels for latter are still limited, making them unaffordable, and many variants have not yet proven ready for full deployment.

EU’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions would also ramp up from more military spending

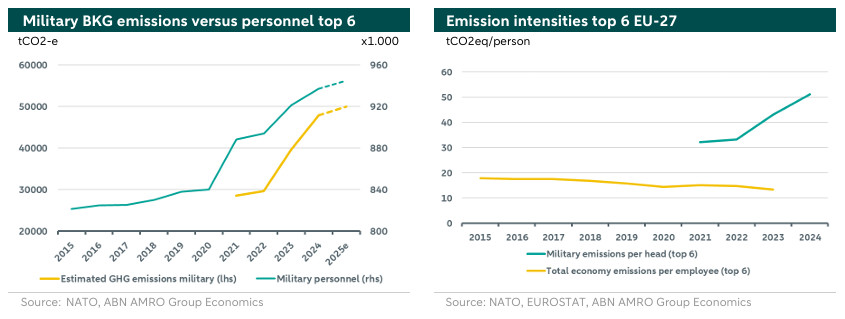

A NATO report provides valuable insight into expectations regarding military expansion and greenhouse gas emissions. The figure on the left below shows the link between an increase in military personnel and military greenhouse gas emissions. The lines in the figure relate to the combined emissions and military personnel of the biggest six countries in the EU-27 (these are France, Germany, Italy, Poland, the Netherlands and Spain). The figure shows that there is a very strong correlation between greenhouse gas emissions and an increase in personnel. More military personnel goes hand in hand with more military equipment and an increase in logistical movements within the defence apparatus.

In addition, the emission intensity of the defence sector and its activities is two to three times higher than that of economic activities. This means that when the military workforce increases due to an influx of personnel from other parts of the economy, emissions will rise.

According to the aforementioned NATO report, both NATO countries and the weapons industry regularly discuss making the defence sector more sustainable, but none of their greening measures have succeeded in reducing emissions so far. ‘Higher military spending will therefore always lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions,’ NATO states in its report.

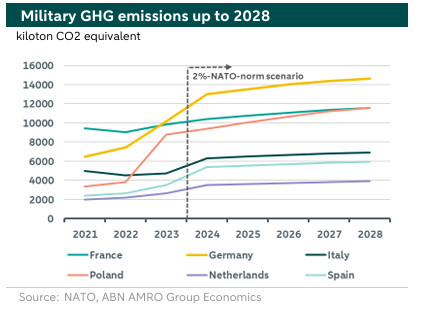

This is also evident from NATO's forecasts up to 2028 (see chart below). NATO assumes that GHG emissions and defence spending will increase by an average of 9% in the period 2025-2028. However, there is a strong possibility that NATO countries will continue increasing their defence spending in the coming years, exceeding the 2% of GDP target. For example, defence spending in the eurozone is expected to rise further from an average of 1.8% to 2.5% of GDP in 2026. With a further increase in defence budgets and spending, greenhouse gas emissions from military activities are also expected to continue rising.

For all NATO countries combined, the increase in both indicators will be of approximately 12% over the same period. This is based on the assumption that all NATO countries will comply with the 2% NATO target during the period until 2028. Moreover, these emissions solely regard scope 1 and 2 emissions, whereas it is important to further consider scope 3 emissions, as the defence sector relies on extensive supply chains. These include, for example, the military technology sector and the broader supply chain, such as IT and telecommunications, facility management and maintenance, construction, waste processing, logistics, healthcare, welfare and catering. As such, estimates regarding scope 3 emissions are very complex and difficult to estimate. Nevertheless, according to the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS), emissions from supply chains for the infrastructure and manufacturing sectors are estimated to be between four and eight times higher than the operational emissions of defence.

Conclusion

All in all, increasing defence spending does not come without a cost. That cost in this case comes in two forms: more investment needed to achieve the 2% NATO target, which could take funds away from climate investments, and at the direct negative impact on emissions. While it is still difficult to calculate how increased military spending will impact climate-related spending, there is a significant risk that more funds allocated to military spending will likely come at a cost of lower funds directed to climate. Furthermore, the increase of military carbon emissions will undoubtedly impair the achievement of EU climate ambitions. The defence sector is – and will remain – largely dependent on fossil fuels, which has a negative impact on the environment. NATO forecasts show that higher military spending, especially in response to geopolitical tensions, will inevitably lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions. As defence has a relative large carbon footprint, urgent measures are needed in this sector to accelerate sustainability and thus reduce the burden on the environment. A first step could be to focus on military activities that are not part of the direct armed forces (such as the administrative staff, military police and support functions). It is much easier to make the processes for these types of military activities carbon-neutral. However, this requires a strong reliance on knowledge and innovation in the military industry.