ESG Economist - EU mulls softening climate ambitions

The European Commission is considering softening its 2040 emission reduction target according to reports. The EC may stick to a proposal for a 90% reduction by 2040, but make the emission reduction back-loaded with a slower pace to 2035. This target would be consistent with a carbon budget of around 1.7 degrees, even assuming an improbable collapse in emissions post 2035. In fact, even a 95% reduction would no longer be consistent with a 1.5 degree pathway given current emission trends. Meanwhile, the use of carbon credits to meet targets may also be allowed, which could push down on ETS prices, blunting incentives. It also seems likely that targets for 2030 and beyond will in any case be missed, which would make any 2040 ambition more difficult to be met.

After the climate U-turn in the US, will the EU follow?

The new US administration has moved away from the country’s previous climate commitments and rolled back existing climate policies. Following this, the private sector started to react, exemplified by major US banks leaving the NZBA (see our note here). As well as the direct impact this will have on the pathway of US carbon emissions, this could have indirect effects on the incentives of other countries to reduce their emissions. After all, global action on climate change poses the classic collective action problem. A country potentially moving faster on decarbonisation than its neighbours could pose challenges to its economy’s competitiveness in the near term. We have already seen signs that the EU is starting to water down its climate policies, for example, by proposing a loosening of climate reporting under the omnibus (see here). But are we seeing further signs, particularly related to climate ambitions?

The 2040 target could be a litmus test

The EU’s decarbonization targets and policies for 2030 are already in place to a significant extent, even though adjustments could still be made, and implementation in many areas still depends on national governments. Hence, it is the region’s discussions about the 2040 target that pose a litmus test on its climate ambitions. In February of last year, the previous European Commission (EC) proposed a new reduction target for net GHG emissions of 90% by 2040 compared to 1990 levels, building on the 55% reduction it hopes to achieve by 2030 (see our note here).

It was left to the new Commission to make the legislative proposal to include the 2040 target in the European Climate Law and to design the post-2030 policy framework. In line with this, the Commission had originally promised to release a draft law in the first quarter of this year. However, Wopke Hoekstra, European Commissioner for Climate, Net Zero and Clean Growth, has signalled that this will now be delayed until ‘before summer’ amid concerns from some governments and political parties across Europe that the 2040 target as previously envisioned would be too stringent.

How the target might be watered down

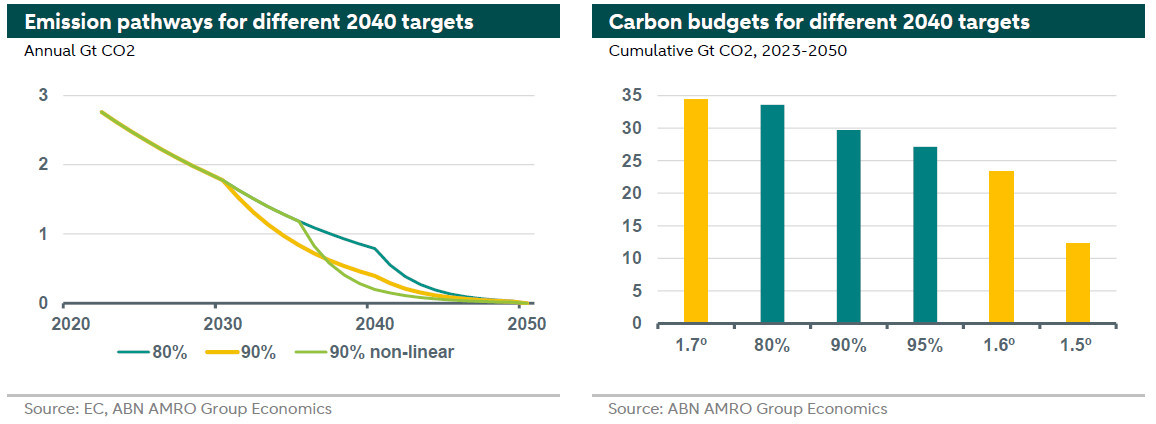

Some have suggested that the 2040 target as proposed by the previous Commission should simply be lowered. For instance, Italy’s government has been calling for the target to be reduced to 80-85%. Although European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is committed to the 90% goal, some in her (and Mr. Hoekstra’s) European People's Party — the largest in the European Parliament – have been critical of the proposed target. This has left the Climate Commissioner scrambling to maintain the overall target, while making compromises to ensure that it is backed by a ‘solid majority’. This is because the legislation would need backing both from national governments and the European parliament. Politico, a digital newspaper that focuses on policy and politics, has set out some of the options being considered based on briefings from officials (see ). According to the source, a non-linear path towards the 2040 target has been suggested. For instance, this would mean a reduced pace of emission cuts up until 2035, followed by steeper cuts in the years thereafter to eventually reach the 2040 target. From a climate perspective, this would mean higher cumulative emissions and therefore a somewhat higher carbon budget overall, given that annual emissions would stay higher for longer. And it is the carbon budget rather than the emissions reduction at any particular point in time that matters for the contribution to global temperature rises (see below). Furthermore, there would be a concern that ‘kicking the can down the road’ would leave too much to do in the last few years of the decade. In that case, either the rapid emissions reductions would not materialize, or the step-up would need to be so rapid that it damages the economy.

A second option being mulled over is allowing emission reductions to be met by buying carbon credits on international markets. This would mark a U-turn from the current approach. Carbon credits are certificates representing quantities of greenhouse gases that have been kept out of the air or removed from it. So essentially, the emission reduction would be made elsewhere in the world and EU countries would be able to use that reduction to meet their own targets at a price. There is little detail on how such a system would work in practice at this stage, for instance, how it would interact with the EU’s Emission Trading System (ETS), which banned the use of international credits in 2020. In addition, some credits are not environmentally robust, in the sense that they represent emissions reductions that were questionable (see here). All this may change in the coming years, given international efforts to make the system more robust under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. In addition, the growth of international credits could help to provide climate funding for poorer countries.

Even if that is the case, the move would have the potential to reduce the incentives for domestic emission reduction more broadly across the EU, if it were to put downward pressure on ETS prices. The current price of voluntary carbon credits is well below that of the ETS. The high use of international credits has been mentioned as a factor that drove down ETS prices between 2008 and 2013 (see ), though the severe global recession obviously played a major role. Yet, carbon prices would likely need to rise sharply to provide the incentives for the emission reduction needed. As higher carbon prices provide incentives to shift to cleaner energy sources, reduce overall energy use and invest in clean technology. A third option is to allow EU countries to allow more negative emissions via carbon removals to meet their target. Finally, the new legislation could allow more flexibility on sector targets. For instance, by allowing target misses in one sector to made up for by stronger emission reduction in another sector.

Banking on a future abrupt collapse in emissions

For the EU to keep its carbon budget (based on its share of current global emissions) consistent with its ‘fair’ contribution to the 1.5 degrees of the Paris Agreement, we estimated in a previous note (see here) that the 2040 target should be set around 92.5%. This assumed that the 55% target for 2030 is met, and that the emission reduction subsequently followed a linear path. This also corresponded to the advice given by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC) when the EC first proposed the 90% target. In that sense, the linear 90% reduction target already fell somewhat short. Crucially, since the proposal, the carbon budget has continued to shrink. As a result, even a 95% reduction would no longer be consistent with a 1.5 degree pathway, suggesting the window for such a pathway is fast closing.

On the basis of a 1.5 degree commitment, one could argue therefore that the EC should be considering stepping targets up, rather than watering them down. Indeed, the non-linear 90% being discussed, or the 80-85% target suggested by the Italian government, would lead to a carbon budget closer to 1.7 degrees (see chart above right). In addition, each of these scenarios factor in an abrupt collapse in emissions further down the line - post 2035 (in case of the non-linear 90% target) and post 2040 (in case of an 80% target) - which seems unrealistic (see chart above left).

Targets are one thing, policies quite another…

Setting impressive headline-grabbing targets is one thing, but policies need to be implemented and funds need to be made available if these targets are to be seen as credible. The EU is currently not on track to meet its 2030 target. Based on recent trends, only 6 of the 27 EU member states are on track (see our note here). For the EU as a whole, existing climate measures alone would result in a reduction by merely 43% in 2030 compared to 1990 (see our note here). Obviously, this would make any 2040 ambition more difficult to meet. At the same time, one could argue that recent policy steps also point in the direction of softening of future ambitions. As part of the recent Omnibus, SMEs were excluded from sustainability disclosure requirements (see our note here). Although the intention is to reduce the administrative burden for businesses, which is understandable, it is worth noting that SMEs make up over 50% of the EU’s GDP and more than 63% of enterprise CO2 and broader GHG emissions (see ) according to the EU’s Platform for Sustainable Finance. The omnibus seems to be relying – perhaps optimistically - on large companies and banks to drive the SME transition, given that these companies are responsible for an important part of their scope 3 emissions. Meanwhile, the European People’s party has also been calling for the EU to scrap its total ban on selling new cars with combustion engines after 2035, arguing that it is necessary to protect the bloc’s car industry. According to the FT (see ), Manfred Weber – the leader of the party – argues that cars with combustion engines should continue to be sold as long as the carbon emissions are offset. Road mobility is a substantially lagging sector in the transition. Emissions from road mobility were 17% higher in 2022 compared to 1990 and recent data have indicated that there has not been a sharp improvement.

Leader, follower or free-rider?

The pressure to water down Europe’s climate goals comes from potentially well-meaning concerns about the economic consequences of a fast transition, especially in an environment of the new US administration’s turn away from climate goals. Industry could become even less competitive. Households could struggle with higher near-term costs. Especially in an environment where many EU governments are already running large government deficits and therefore may feel that they do not have the money to support the transition or buffer the blow for the most vulnerable.

The costs of climate change on the global economy are widely estimated to far-exceed the costs of the transition, but the calculus could become different for any individual country or even bloc as the costs significantly depend on the actions of others. For instance, emission reductions in the EU have been offset by rising emissions elsewhere in the world over the last few years. EU emissions were only around 6% of the total in 2023. In a scenario where other countries are lagging their emission reductions, some make the case that it is better for the EU to be a follower, as the region will incur the costs of climate change in any case, and perhaps it is better in that situation to invest in climate adaptation rather than mitigation. Even in a scenario where other countries step up their game, it might be tempting to be a free rider that benefits from the reduced costs of climate change without having to pay for the transition.

However, this kind of thinking ignores the EU’s role as a global climate leader as well as the opportunities it could grasp. The EU’s role goes beyond the size of its emissions, as if it continues to play a leadership role, it can encourage stronger climate policies around the world. A good example is how the region’s pioneer EU Taxonomy has encouraged many other countries to also develop their own green taxonomies, including high emitters such as China and Russia. Currently, there are over 40 countries that either developed or are in the process of developing a green taxonomy. Hence, EU’s role goes beyond a lighthouse function. Furthermore, large investments in transition technologies can allow the achievement of the scale necessary to achieve technical readiness. In addition, a leadership role can also allow the EU to grow new clean-tech sectors that benefit the European economy.