ESG Economist - Pace of EU emission reduction needs to increase by 50% to meet target

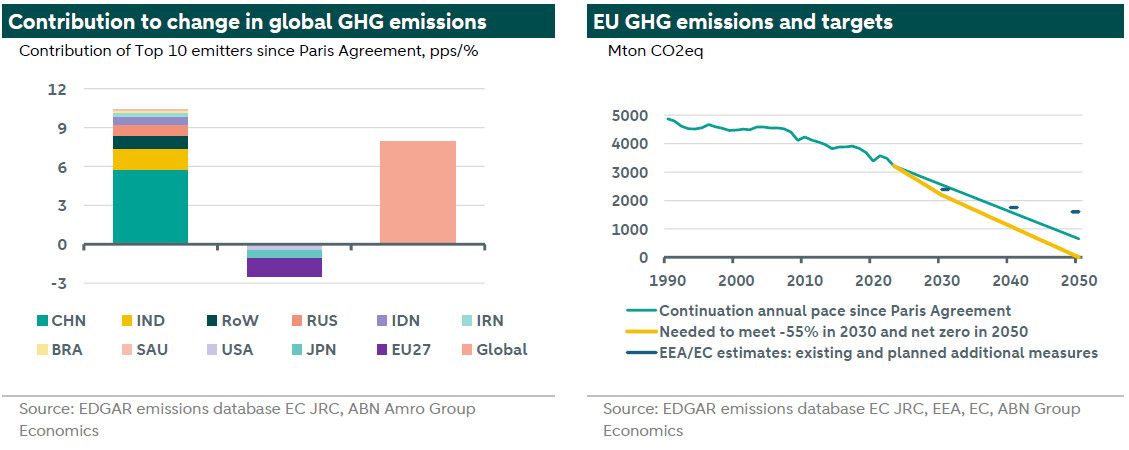

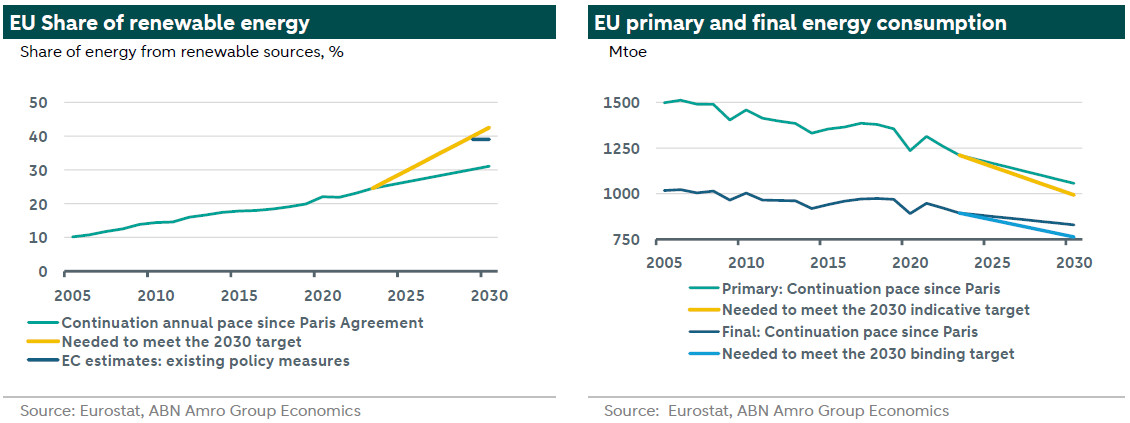

The EU is one of only a few countries/regions in the global top ten of GHG emitters that has significantly reduced emissions since the Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016. The others being Japan and the US. Nevertheless, the pace of emissions reduction in the EU needs to be stepped up to reach the targets set in the EU Green Deal. Other key EU targets for 2030, such as the share of renewable energy in energy consumption and the amount of primary and final energy consumption will probably not be met either if the pace of increase/decrease is not stepped up noticeably. With only about six years to go, we evaluate in this note the likelihood of the EU meeting its main climate goals in 2030.

Since the Paris agreement, considerable progress has been made in moving towards the EU’s key climate targets for 2030, but the pace of improvement needs to be stepped up

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the EU have fallen noticeably since the Paris agreement, yet the pace of average annual reduction needs to increase by more than 50% to reach the 2030 target of -55% versus 1990 and the final target of net zero in 2050

The 2030 targets for primary and final energy consumption in the EU can only be met if the pace of reduction in primary energy consumption increased by around 40%, whereas the pace of reduction in final energy consumption needs to double

The EU target for the share of renewable sources in the gross final energy consumption will only be met if the share rose by around 2.5 percentage points per year until 2030, which is almost three times more than the average annual increase observed since the Paris Agreement

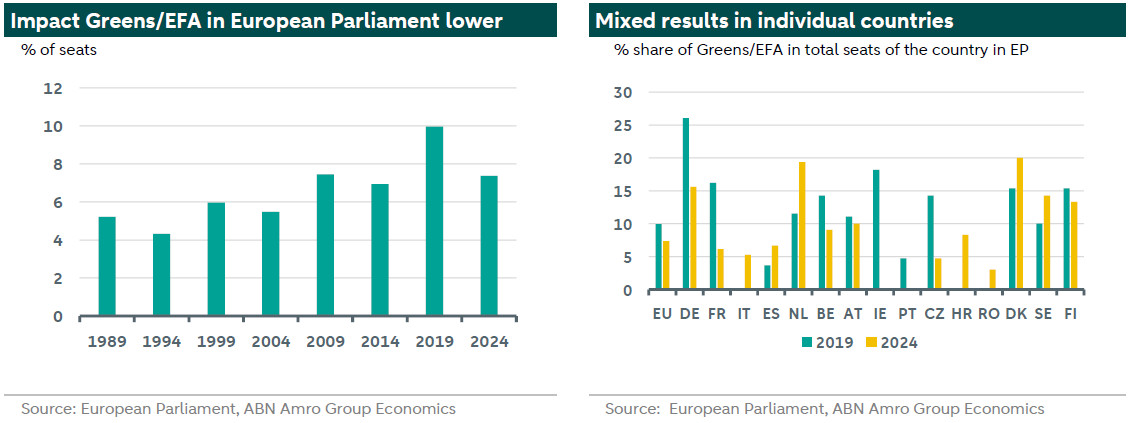

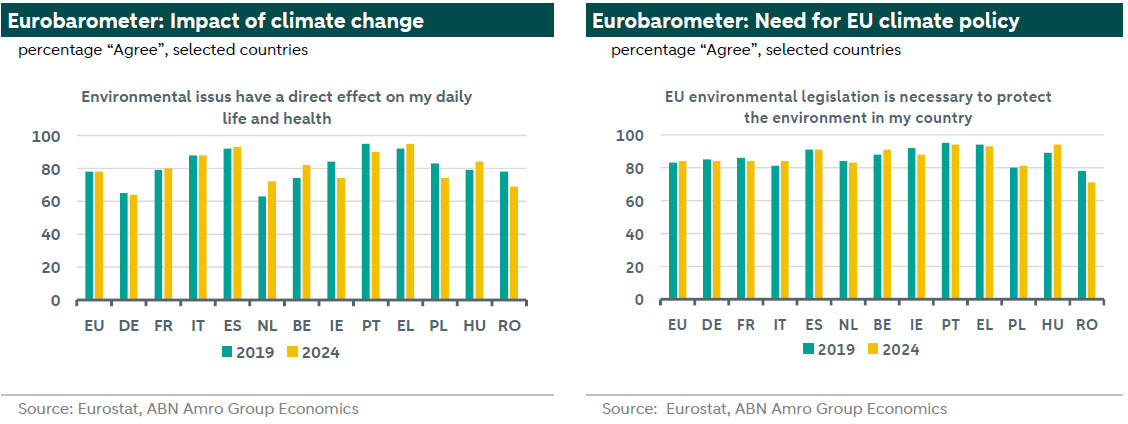

Implementation of existing climate policies and additional plans crucially depends on political and public support. During the 2024 EU elections green parties have lost support, yet there was quite some variation on a country level

In addition, the Eurobarometer shows that a large majority of EU citizens thinks that their life and health is impacted by climate change on a daily basis, and also are of the opinion that EU policy is needed to fight climate change

GHG emissions reduction outside of the EU ETS needs to be stepped up

Within the global Top 10 of Greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting countries/regions, the EU has contributed the most negatively to the global change in emissions since the Paris Agreement (see graph left below). Whereas total global emissions rose by around 8% between 2016 and 2023, EU emissions fell by more than 17%, reducing the total global change in emissions by 1.4pps. That said, the pace of reduction in the EU needs to be stepped up in order to meet the EU target of -55% in 2030 versus 1990 and net zero emissions in 2050. If the average annual pace of reduction since the Paris Agreement were maintained until 2030, the total reduction would be around 48% by 2030. According to the European Environment Agency (EEA, see ) and European Commission (EC, see ) existing climate measures alone would result in a reduction by merely 43% in 2030 compared to 1990. However, in 2024, a large number of the EU member states have either updated their emission projections or submitted their final updated National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) to the EC. According to the EC and EEA these additional measures would probably raise the reduction in GHG to around 51% by 2030.

There is a difference between GHG emission by sectors that are covered by the European Emission Trading System (ETS - for more information on ETS see our previous notes here and here) and emissions by sectors not covered by ETS, which are governed by the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR). ETS emissions were 48% lower in 2023 than in 2005 (the year when EU-ETS was first introduced) and are expected to be 62% lower in 2030 compared to 2005. In contrast, emissions by sectors governed by the ESR were only 19% lower in 2023 compared to 2005. Based on current policy measures and announced additional plans – including a new ETS for these sectors - ESR emissions are expected to miss their targets, which are set at the national level and differ per country (see ).

Looking beyond 2030, the projections based on the NECPs reveal a widening gap between emissions and the targets for 2040 and 2050 according to the EEA and EC. The EC proposed an intermediate target for 2040 of 90% reduction versus 1990 levels in February 2024. The newly elected European Parliament and the Member States are now discussing this target. The Commission, which took office in December 2024, will put forward legislative proposals on that basis. According to the projections by the EEA and EC, existing policy measures and announced additional policy plans will result in a reduction of just 65% versus 1990 by 2040, in contrast to that 90% target. There will only be very limited extra emissions reduction in the years between 2040 and 2050 (see graph right above).

Targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency also likely to be missed

Two other key EU climate targets for 2030 are about the share of renewable energy in total energy consumption and energy efficiency (primary energy consumption and final energy consumption). The 2030 target for the renewable energy share is 42.5% and the result for 2023 was 24.5%, up from around 10% in 2005. The largest growth from 2005 to 2023 in terms of the various (associated) technologies was solar power (24-fold growth), followed by heat pumps (12-fold) and wind power (6-fold). The EC estimates that existing policy plans would raise the share to around 39% in 2030 and additional policy measures are needed to reach the target. In June 2024 a large number of (but not all) Member States submitted their final updated NECPs to the EC. These have not yet been fully assessed by the EC but the new plans could increase the share of renewable energy in 2030. We have looked at the changes in the draft updated NECPs and the final updated NECPs of a number of big member states and it seems that an improvement in the 2030 outcome of around 1 percentage point (to around 40%) will be achieved.

Turning to energy efficiency, the EU has set a binding final energy consumption target at no more than 763Mtoe by 2030 and an indicative target for primary energy consumption at no more than 992.5Mtoe. Since the Paris Agreement primary energy consumption has fallen by 11.3% in total, whereas final energy consumption has declined by 6.8%. In order to meet the 2030 EU target for primary energy consumption, the average annual pace of reduction needs to be stepped up by around 40% compared to the period 2016-2023. The annual average pace of reduction in final energy use needs to double during the years up to 2030. According to the EC’s assessment of the draft updated NECPs the EU target for final energy consumption would by overshot by around 7% in 2030 based on existing policy measures. The EC’s assessment of the final updated NECPs and the planned additional policy measures mentioned in those NECPs could reduce the gap between the expected outcome and target for 2030 somewhat.

Implementation is key

The entire EU Fit-for-55 climate policy package has been adopted by the European Parliament and Council, which means that EU policies are now aligned with the updated 2030 targets set in the European Climate Law, and that the focus has now shifted to implementation at the national level. In this respect changes in the political landscape of the Member States is important but also the general attitude towards climate change amongst EU citizens.

The Greens/EFA parliamentary group currently holds 7.4% of the seats in European Parliament, lower than after the 2019 elections when they won 10% of the seats. The right graph below shows the results of a selected number of individual countries where the number of seats held by the Greens/EFA in EP was larger than zero in either 2019 or 2024. The most noticeable declines were registered in Germany, France, Ireland, Belgium, Portugal and Czechia, whereas the most noticeable rises were in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Croatia, Romania, Denmark and Sweden.

Besides their voting behaviour during national or European elections, European citizens also have other means at their disposal to have an impact on implementation of climate policy by governments and companies, for instance by filing climate litigation cases before the Courts of the European Union or the European Court of Human Rights (see for instance , and ). Indeed, since around 2015, European climate litigation has followed a rising trend, with courts from all over Europe seeing an increasing number and diversity of climate cases filed before them. On top of this citizens can file a complaint at the EC if a country does not comply to the European climate laws, after which the EC can start an infringement procedure (see ). According to the renowned Eurobarometer [1] a large majority of EU citizens judge that environmental issues have a direct effect on their daily life and health (see left graph below). The Eurobarometer also reveals that more 84% of EU citizens are of the opinion that EU environmental legislation is necessary to protect the environment in their country.

Conclusion

On a global scale the EU is one of few regions/countries that has contributed to reducing global GHG emissions. There is broad support amongst EU citizens for the view that further climate policy at the EU level is needed and a there is a rising trend in climate litigation in Europe. Therefore, it seems likely that the EU will continue to contribute to a global reduction in GHG emissions and will also continue to implement other measures that are needed to limit global warming. Still, based on trends since the Paris agreement, the EU is currently on course to miss its 2030 targets.

[1] A cross-country polling instrument used by the EC, the European Parliament and other EU institutions and agencies to monitor regularly the state of public opinion in Europe on issues related to the European Union as well as attitudes on subjects of political or social nature.