ESG Strategist - Assessing the impact of joining the NZBA on banks’ bond spreads

In April 2021, the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) formed the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), an initiative that brings together banks across the globe committed to align their lending, investment, and capital markets activities with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. By signing the NZBA, banks are committing, amongst other things, to (1) transition the operational and attributable GHG emissions from their lending and investment portfolios to align with pathways to net-zero by 2050 or sooner, and, (2) within 18 months of joining, set targets for 2030 or sooner, and a 2050 target, with intermediary targets to be set every 5 years from 2030 onwards. By committing to a net-zero pathway and subsequently setting decarbonization targets, a bank is not only signalling its commitment to sustainability to investors, but is also committed to decrease its exposure to climate risks. This can be done by either divesting from polluting companies or by assisting its high-emitting clients to reduce their own emissions. As such, signing to the NZBA might be supportive of the bank’s outlook, and, as consequence, of the banks’ bond spreads. In this note, we aim to understand whether signing to the NZBA (referred to as “the event” from now onwards) had an effect on signatory banks’ bond spreads. Using a fixed effects model, we calculate the direction and significance of signing to the NZBA on banks’ bond spreads. The note follows as: in the second section, we explain the sample and the methodology. In the third section, we present the results and interpret them, and elaborate on the limitations of our research. And, in the final section, we conclude.

Giovanni Gentile

Fixed Income Strategist

Signing to the NZBA signals a bank’s commitment towards sustainability, which could potentially reduce a bank’s exposure to climate risks. Ultimately, this might have a tightening effect on bond spreads

The aim of this research is to evaluate the effect on banks’ bond spreads of signing to the NZBA

Our results indicate that banks that have joined the NZBA saw a widening of their bond spreads – in contrast to our hypothesis

Reasons for this might be related to investors foreseeing stricter lending criteria, higher compliance costs, and/or perception of an additional risk associated with transitioning to sustainable practices. And, as a result, demand higher compensation from banks

Sample and methodology

In order to build a balanced panel data set, we need to have the same number of observations for each unit in the sample. That is, if we want to evaluate the impact on banks’ bond spreads, we need to make sure that each bond has the same number of observations (i.e. we need to observe, for each bond, their z-spreads for the same number of months). As such, we start by filtering the NZBA signatory banks to only include European banks that signed up to the NZBA between 2021 and 2023. As a second step, for each bank in the sample, we have to find one or more bonds that were active before joining the NZBA and remained active afterwards. This results in a total of 112 bonds. However, given that we aim for a balanced data set, we have to exclude bonds that do not meet the following criteria: (1) being active 10 months prior to the event, and (2) being active 10 months after the event. This results in a final sample of 38 senior bonds from 24 different European banks, each with 21 monthly observations in time. Of these 38 bonds, only one is a green bond.

Our aim is now to understand what might have driven the z-spreads of these 38 bonds in that time period, in order to isolate the impact of joining the NZBA.

In our analysis, for each bond and point in time, we consider six (independent) variables. The first is the credit rating of the bond as provided by Moody’s. As these ratings are expressed in letters, for processing purposes, we have matched each rating to a number. That is, a rating of AAA was assigned a value of 1, a rating of AA a value of 2, and so on. This implies that the lower the rating, the higher the number.

The second one is an issuer-specific variable, the Bloomberg default probability (matched to the remaining maturity of the bond in question). Then, we consider three variables representative of the market as well as of macroeconomic conditions: the 12-month Euribor rate, the Bloomberg Index on European equities (ticker: SX7E), and the Eurozone Consumer Price Index (CPI) yoy. The rationale for including the bank’s equity index regards the fact that spread movements are usually responsive to movements in the equity market. Finally, our variable of interest is a dummy variable which equals 1 if the bank is a signatory of the NZBA at that point in time, and 0 otherwise.

Regarding the methodology, there are three main panel regression models available: pooled OLS, the fixed effects model, and the random effects model. In this research, we opted to use the fixed effects panel regression, given that this model controls for unobserved variables that could vary across banks, but are constant over time (such as management quality, corporate culture, or risk appetite). The key idea behind this model is that it accounts for these unobserved variables by allowing each entity to have its own intercept in the regression model. We discuss the results in the following section.

Results & interpretation

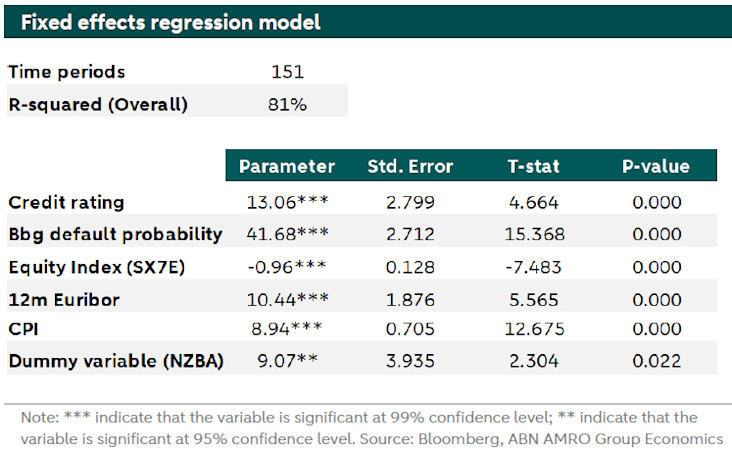

According to the table below, overall, the independent variables included in our model explain 81% of the variability of z-spreads, and are all significant with a 95% confidence level.

We interpret the results as following: firstly, with regards to the credit rating, our results confirm our expectations that the lower the credit rating, the wider the credit spread. In this case, a one-notch upgrade in the bank’s credit rating, results in a 13bp wider z-spread, all else equal. This result is statistically significant at the 95% confidence-level.

Results display a similar reasoning for the probability of default: the higher the probability of default, the wider the bond spreads.

With regards to the bank’s equity index, the negative sign of the estimated coefficient indicates that when the equity index increases (stock prices of banks are traded higher), credit spreads tend to tighten. That is also in line with our expectations.

The 12-month Euribor and CPI are control variables for the macroeconomic environment. As expected, both of these variables have a positive coefficient. That is because as inflation increases, the purchasing power of households is negatively impacted. As result, central banks start raising interest rates, in order to slow-down the economy. Although banks’ net interest margins improve as interest rates widen, the general economic activity tends to slow down, ultimately impairing banks’ volume of loans. This results in a deterioration of the outlook for banks. As such, we expect a higher Euribor and a higher CPI to have a widening effect in banks’ credit spreads. That is indeed the case in our model, and both variables are statistically significant at a 95% confidence level. We note that these results take into account a period of high CPI and interest rates (where most of our sample data lies), which could be biasing our results.

Finally, we are left with our variable of interest: the event of signing to the NZBA. The model’s output indicates that this variable is statistically significant with a 95% confidence level. That is, there is a lasting effect on a bank’s bond spreads, if a bank decides to join the NZBA. However, while we expected the signing of the NZBA to be positive to a bank’s exposure to climate risks, which could consequently be translated into tighter credit spreads, our results indicate the opposite.

According to our results, after a bank signs to the NZBA, its bond spread ultimately widens by approximately 9bp, all else equal. That means that investors do not perceive this commitment to be positive for a bank. Some reasons for this might be:

stricter lending criteria/less loan availability: being part of the NZBA may require banks to implement more stringent lending criteria, which can restrict credit availability for certain sectors. Reduced access to credit can lead to higher perceived risks for those borrowers, thus widening credit spreads as lenders adjust to the altered risk landscape;

a higher risk perception: if a bank is perceived to be taking on additional risk associated with transitioning to sustainable practices, investors might demand a higher risk premium. This change in market perception could widen credit spreads as investors seek compensation for the perceived increase in risk;

compliance costs: being part of the NZBA may involve stricter (and higher) requirements related to sustainability, which can impose additional costs on banks. These costs may impact profitability, which would result in investors demanding a higher return for the bond (wider credit spreads);

scrutiny around NZBA: the market may have mixed sentiments about the effectiveness and enforceability of NZBA commitments. If investors believe that the bank’s transition strategy is less credible or that it faces challenges in achieving its net zero goals, they might demand a higher yield (wider spreads) to compensate for that.

Limitations & conclusion

Although we consider this analysis a good starting point for future research, we would like to note some caveats: the first is that our sample is considerably small, which jeopardizes the strength of our results. Moreover, we use monthly data, which ideally would be daily. Nevertheless, the results that we find are statistically significant, having proven that there seems to be an effect on bank’s credit spreads of joining NZBA.

Surprisingly, this effect was actually the opposite of what we expected, and almost paradoxical. While banks seem to be actively committing to reduce their exposure to climate risks and supporting the transition, investors seem to perceive these efforts as the emergence of new risks and even more uncertainty. Furthermore, it could also be that investors are sceptical of banks’ intentions. Although the commitment signals the interest of banks about the topic, investors still lack the evidence of any actions – or might be even fearing those actions.

As for future research, it could be interesting to analyse whether green bonds from banks who have joined the NZBA trade with a higher greenium (that is – lower spread between green and conventional bonds from the same issuer). That would build on top of the research published by the ECB () in December 2022, where it showed that green bonds issued banks that have committed to the UNEP FI trade at an economically and statistically significant greenium of 17.38 bps.

This note was done with reference to the Master Thesis of Tom de Haan “50 Shades of Green: Interpretation of Climate Risk in the European Banking Sector”.