ESG Strategist - Do defence investments and ESG mix?

Investments in the defence sector are projected to rise in the coming years due to growing geopolitical concerns. Given that public investment alone is insufficient to meet the sector's needs, private investors are expected to ramp up their defence-related investments. However, this prompts several questions regarding which funds could participate, especially considering the social implications of this issue. Therefore, in this note, we explore which funds are currently investing in defence, assess whether legislation permits both ESG and non-ESG funds to invest in defence-related companies, and provide a comprehensive evaluation of the involvement of ESG funds, particularly Article 9 funds, in defence-related investments.

On average, around 18% of Article 8 funds, and 0.2% of Article 9 funds currently invest in defence-related companies

European law permits ESG funds to invest in defence-related companies, provided certain conditions are met

However, if these funds also carry an ESG-related term in its name, ESMA prohibits the investment in controversial weapons

An analysis reveals that still 0.20% and 0.24% of all Article 8 and 9 funds that carry an ESG-related term in its name invest in controversial weapons, according to Bloomberg definition

Investments in defence companies appear to be misaligned with social objectives, such as those outlined by the SFDR…

…But the European Commission disagrees, asserting that the defence industry enhances sustainability through its contributions to resilience, security, and peace

Many non-ESG funds currently abstain from investing in defence-related companies, but could choose to do so, thereby reducing the need for ESG fund involvement

Which funds are investing in defence?

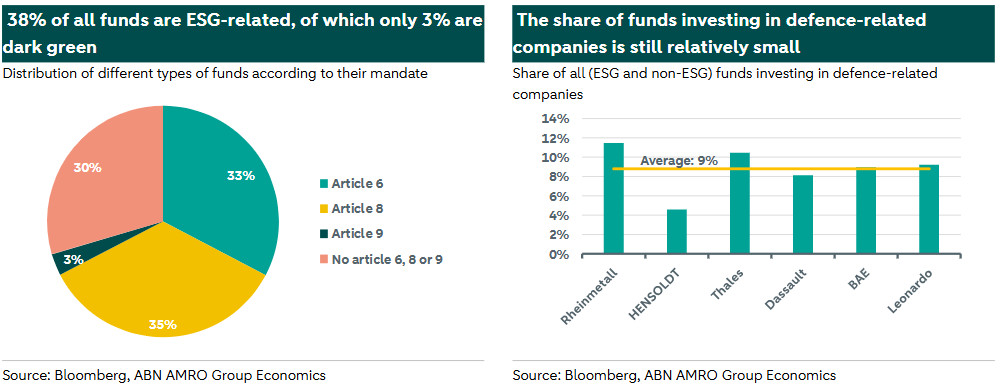

According to Bloomberg, there are a total of 27,129 funds under the EU’s UCITS directive. From these, 33% are Article 6 funds, 35% are Article 8 funds, 3% are Article 9 funds, and 30% do not report any Sustainability Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) denomination related to sustainability. Article 8 and 9 funds are classified in the SFDR as follows: Article 8 funds promote environmental or social characteristics, or a combination thereof, while Article 9 funds aim for sustainable investments as their primary objective.

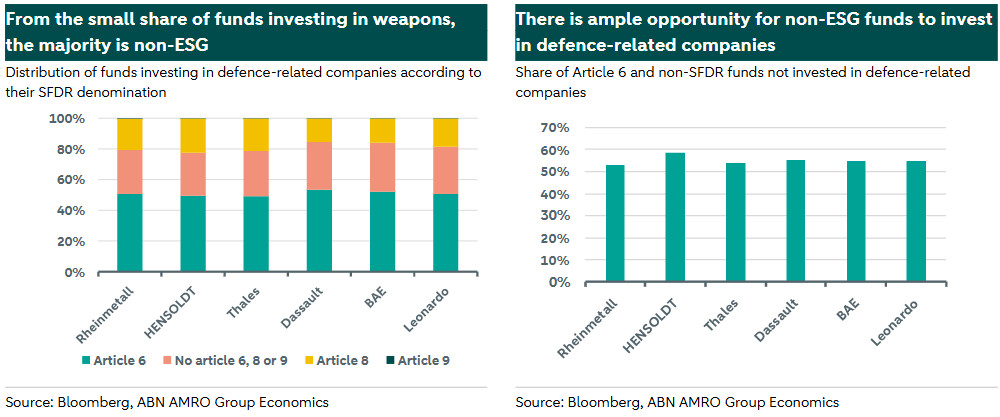

In order to evaluate exposure to companies involved with (controversial) weapons, we use a sample of six defence-related companies: Dassault Aviation SA, BAE Systems plc, Leonardo SpA, Rheinmetall AG, HENSOLDT AG, and Thales SA. As shown in the chart above on the right, on average, 9% of all EU funds governed by the UCITS directive invest (regardless of their sustainability focus) invest in these six companies. Additionally, the graph below highlights the distribution of the funds that do invest in defence-related companies based on their SFDR classification. It shows that the majority consists of non-ESG funds, encompassing both Article 6 funds and those without any classification. However, there are still on average nearly 20% of all funds that invest in defence companies that are classified as Article 8 or 9 according to the SFDR.

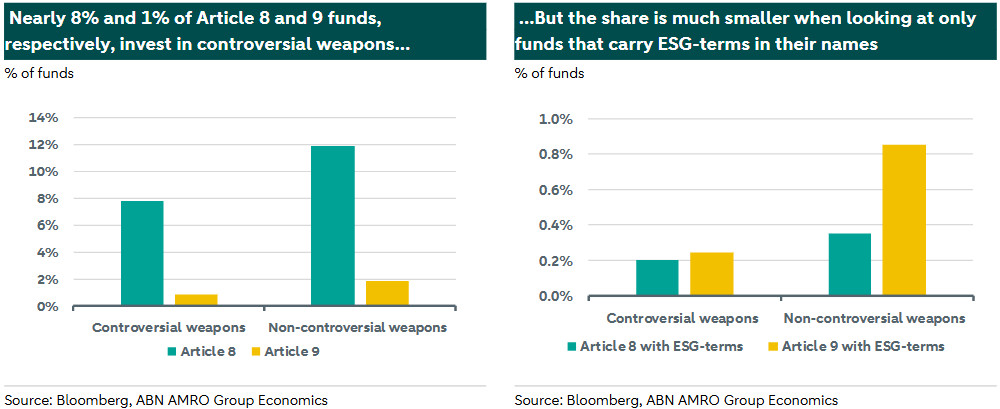

In theory, the SFDR does not limit Article 8 and 9 funds to invest in defence, including in controversial weapons [1] as long as those investments are publicly and transparently mentioned in the Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) report that funds need to publish on an annual basis. However, some exceptions apply. Last year, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published name guidelines for ESG funds (), with the aim to avoid greenwashing and to promote transparency. According to those rules, a fund that has ESG or sustainability-related terms in its name must exclude the investments stipulated by either the EU Climate Transition Benchmarks (CTB) or the EU-Paris aligned Benchmarks (PAB). The benchmark to which each fund must comply with depends on the ESG-related term included in its name. Nevertheless, there are a few exclusions which are common to both benchmarks, one of them being controversial weapons. Therefore, it is anticipated that Article 8 and 9 funds that align with the PAB/CTB exclude investments in companies involved in controversial weapons.

The classification of which companies are involved with controversial weapons varies among different providers, largely due to the absence of a standardized European benchmark and Social Taxonomy. For example, using the same sample of six companies as mentioned above, only BAE Systems is identified as involved with controversial weapons according to Sustainalytics, but the sample is much larger when using the Bloomberg classification. In this analysis, we will rely on the Bloomberg list to evaluate exposure of ESG funds to controversial weapons. Using the same sample of defence-related companies, three are identified as being involved with controversial weapons according to Bloomberg: Dassault Aviation SA, BAE Systems plc and Leonardo SpA.

Therefore, we conduct an additional analysis of Article 8 and 9 funds’ names. As we previously stated, Article 8 and 9 funds that have an ESG-related term in their name must comply with PAB/CTB, which does not allow investments in companies involved in controversial weapons. In our sample of Article 8 and 9 funds that invest in the three companies flagged by Bloomberg as being involved with controversial weapons, we evaluate how many of those have ESG-related terms in their name (such as "ESG”, “green” and “sustainable”). It was previously noted that around 8% of all Article 8 and 1% of all Article 9 funds invest in at least one of these companies. However, only around 0.20% of Article 8 funds with ESG-related terms in their names invest in these controversial weapons companies . For Article 9 funds, only 0.24% invest in controversial weapon’s companies and have ESG-related terms in their names (see charts below).

Overall, our findings indicate that there is still a significant share of Article 8 and 9 funds that invest in defence-related companies, including those involved with controversial weapons. However, only a very small share of funds appear to be in breach with SFDR and ESMA guidelines, which restrict investment in companies involved with controversial weapons if the fund carries an ESG-related term in its name. Furthermore, the fact that on average, only 9% of all funds invest in defence-related companies implies that there still is ample opportunity for private investors to engage in this sector. Importantly, the responsibility to invest does not necessarily fall on ESG funds, considering the predominance of non-ESG funds and the fact that only a limited fraction of these funds currently invests in defence-related companies.

How does the SFDR define “social objective”?

The inclusion of defence-related companies in ESG fund portfolios prompts an important inquiry: Do investments in defence-related companies align with the sustainable objectives or the promotion of environmental and social characteristics that ESG funds typically uphold?

The SFDR defines a sustainable investment as an “investment in an economic activity that contributes to an environmental objective (…) or to a social objective, in particular (i) an investment that contributes to tackling inequality or that fosters social cohesion, social integration and labour relations, or (ii) an investment in human capital or economically or socially disadvantaged communities, provided that such investments do not significantly harm any of those objectives and that the investee companies follow good governance practices, in particular with respect to sound management structures, employee relations, remuneration of staff and tax compliance”. On the basis of this definition, it does not seem that an investment in a defence company aligns with a social objective, given that it does not directly align with the goals of tackling inequality, fostering social cohesion or integration, improving labour relations, or investing in human capital or disadvantaged communities,

European Commission emphasises role of defence in resilience

The European Commission (EC) disagrees with the notion that defence-related investments do not directly support sustainability goals (see ). Instead, the EC emphasizes that, except for weapons prohibited by international conventions—which are deemed incompatible with social sustainability, such as controversial weapons—the defence industry can contribute positively to sustainability through its role in fostering resilience, security, and peace. Furthermore, the EC clarifies that under the EU sustainable finance framework, there is no rule, nor any planned rule, that restricts private investments in the defence sector. Sustainability disclosures and preferences apply uniformly across all industries, and the absence of a 'social Taxonomy' indicates no intention to single out any sector. Additionally, the exclusion of defence activities from the EU's Environmental Taxonomy does not prejudge their environmental performance, nor should it impede their access to finance.

The argument of the EC centres therefore around the notion that sustainability and resilience are interconnected concepts. And indeed, we have seen examples in the market, such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (ERPB) of dedicated resilience green bonds. However, while these are connected concepts, they are distinct in nature. Resilience is defined as the capacity of systems (ecological, social, economic) to absorb shocks and adapt to change. As such, sustainability (both environmental and social) are an important pillar of resilience. Concurrently, defence is also a part of resilience. Investing in defence promotes security and the sovereign’s ability to absorb shocks coming from war and conflict. However, one can argue that while resilience and sustainability overlap in several areas, they are not synonyms. As such, one can invest in resilience without necessarily promoting sustainability. Hence, one could argue that resilience is a necessary, although not a sufficient condition for sustainability.

A complex and nuanced issue

In conclusion, there are strong arguments both supporting and opposing the inclusion of ESG funds in defence-related companies. On one hand, European regulations allow these funds to invest in both controversial and non-controversial weapons, provided they comply with ESMA guidelines and are transparent about their investments, while also the European Commission supports such investments for their role in enhancing resilience. On the other hand, the SFDR's definition of a social objective implies that investing in defence-related companies may not directly align with these goals. Furthermore, the SFDR also prohibits investments in controversial weapons if the fund carries an ESG-related term in its name.

Despite this, as previously noted, only a small fraction of funds under the EU’s UCITS directive currently invest in defence-related companies. Consequently, a considerable number of non-ESG funds remain available to invest in defence companies, thus reducing the need for ESG funds’ involvement.