ESG Strategist - How exposed are companies and banks to biodiversity risks?

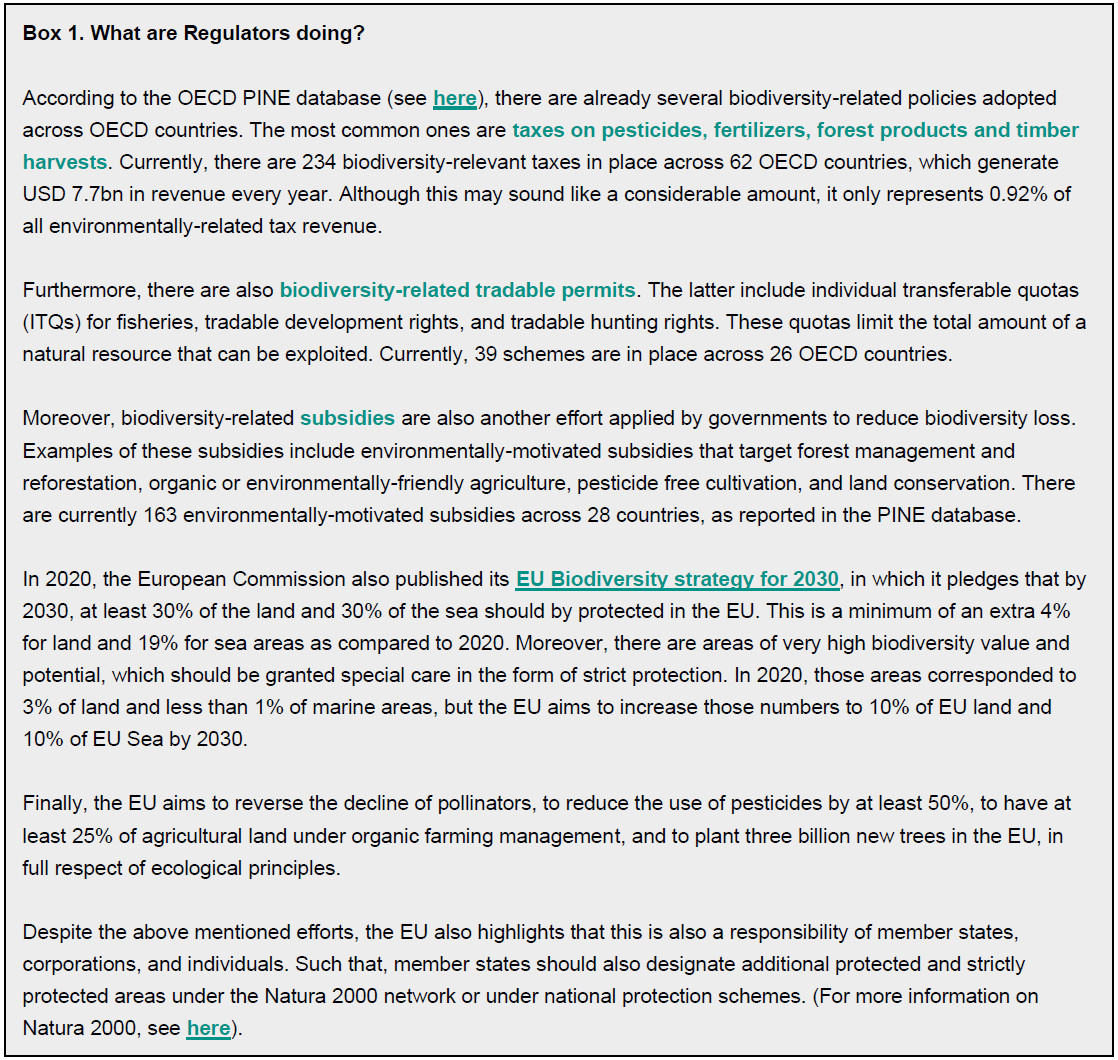

Biodiversity stands for biological diversity. The loss of biodiversity translates into the loss of services provided by ecosystems to the real economy. There are two types of risks associated with biodiversity: physical and transitions risks. Physical risks stem from the loss of biodiversity (for instance, disappearance of animal pollinators, like bees), and transition risks stem from regulations/policies introduced by regulators to mitigate biodiversity loss (such as the introduction of a tax on fertilizers or the implementation of Natura 2000). Physical risks are captured by how much a sector depends on biodiversity (e.g. agriculture depends a lot on animal pollinators, like bees). And transition risks are captured by how much a sector impacts biodiversity (i.e. the more damage a firm causes, the more likely it is to be hit by policies acting against it). The ENCORE database provides qualitative assessments for each sector and sub-sector on their exposure to biodiversity risks and we use these to calculate quantitative biodiversity sector exposure scores. As per existing regulation, banks are required to report their loan book exposure per sector, according to the NACE categorisation. Hence, by combining banks’ loan book exposure per sector and sector scores on biodiversity dependence and impact, we were able to calculate individual banks’ exposure to biodiversity loss risks. Furthermore, we used Natural Language Processing to assess a bank’s awareness of its balance sheet exposure to biodiversity risks.

Co-author - Giovanni Gentile – Data Scientist | giovanni.gentile@nl.abnamro.com

Introduction

Life as we know it might well be at risk. Approximately one million species are currently on the brink of extinction, and, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the world already lost an estimated EUR 3.5 - 18.5 trillion per year in ecosystem services from 1997 to 2011 due to land-cover change. Furthermore, global temperatures are on a rising trend and are set to rise significantly further even on the basis of positive scenarios. In this ESG Strategist note we take some first steps in to assessing the biodiversity risks for different corporate sectors as well as individual banks. We then go on to provide a measure of how seriously banks seem to be taking these risks in their communications relative to climate risks, which have up to now been much more in the spotlight.

According to Target 14 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, each sovereign should “ensure the full integration of biodiversity and its multiple values into policies, regulations, planning and development processes (…) within and across all levels of government and across all sectors, in particular those with significant impacts on biodiversity ”. The Framework was published after the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP 15) that took place in December 2022, where the participants agreed on the new set of goals for nature over the next decade.

These goals set the scene for what looks to become one of the hottest topics in the sustainability landscape: biodiversity. In recent years, national central banks like the Bank of England (BoE), Banque de France, and the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) published reports estimating the exposure of financial institutions in their countries to biodiversity loss risks. And more recently, the European Central Bank (ECB) also published a written statement () revealing that it would publish a report in 2023 showing how much the euro area economy and financial sector are exposed to risks related to ecosystem services (see more on this below). This report is yet to be published.

Despite the above-mentioned efforts, financial institutions, including banks, still assign low importance to biodiversity, underestimating the financial risks related to it. Estimating these risks is not a simple exercise as each bank needs to theoretically assess the biodiversity exposure of each individual company in its portfolio. Nevertheless, the assessment of this exposure would support banks into improving their risk management.

In this research note, we explain conceptually how to think about biodiversity risks and then go on to provide a framework on how to assess these risks across different corporate sectors as well as individual banks. Finally, we assess to what extent banks are aware of these risks.

First, what is biodiversity?

Biodiversity stands for biological diversity, and captures the variety and variability of life on Earth. Furthermore, ecosystems – which entail all the living things in a particular area as well as the non-living things – are built upon the basis of biodiversity. As such, the loss of biodiversity in a certain ecosystem translates into a loss of the services that the ecosystems provide to the real economy. There are four different types of ecosystem services :

Provisioning services of tangible products, such as food, timber and cotton;

Regulating services, such as animal pollination, air and water treatment, and soil fertility;

Cultural services, which are ecosystem contributions to sectors like education, recreation, and tourism;

Supporting services, such as the nutrient cycle, soil conservation and habitat creation.

The diversity of species are of crucial importance to ensuring that ecosystems are stable and function well over the longer term. Such that, the loss of biodiversity would translate into economic consequences for companies that can be severe, and hard to predict.

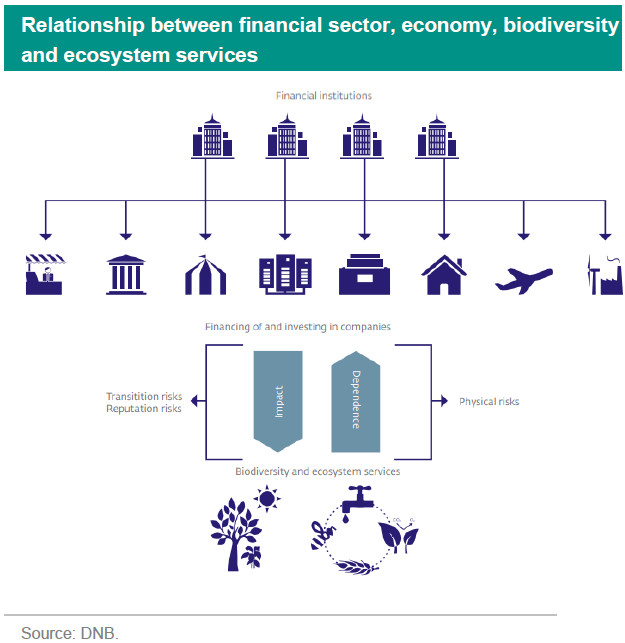

Despite the complexity of calculating a company’s exposure to biodiversity, regulators have been developing tools and methodologies in order to evaluate the exposure of firms to biodiversity loss, and, ultimately, to quantify financial institutions’ exposure to these companies. Below, we plot a graph depicting the relationship of ecosystem services, with non-financial and financial institutions.

But, what are biodiversity risks?

The first challenge for regulators is defining what type of risks companies are facing. Risks can either be physical, stemming from the loss of biodiversity, like the extinction of bees, which leads to the disappearance of animal pollination. Or can be transition risks, stemming from regulations adopted by governments to avoid biodiversity loss, like the introduction of taxes on fertilizers.

Furthermore, these risks will have different consequences throughout the value chain. For instance, the loss of crop production can have a negative impact on the profitability of primary producers (first-order dependency of biodiversity), but it will also affect raw material prices that food processors face (second-order dependency). In their reports, regulators only accounted for first-order dependencies, given how complex it would be to capture all ecosystem services involved in a company’s operations. As such, the outcomes presented in the reports are most likely to represent an underestimation of the risks.

How to quantify physical and transition risks?

The physical risks related to biodiversity are captured by the dependence of a company on a certain ecosystem service. Specifically, a business that is highly dependent on ecosystem services is more likely to be directly affected by a physical shock. Regarding transition risks, these are captured by how much a company impacts the ecosystem.. A business with a significant negative impact on biodiversity has a higher chance of being affected by biodiversity policies (transition shock) than a business with a low impact.

How can a financial institution start to map the dependence and impact of the companies in its loan book? The provides biodiversity dependence and impact scores by sector and sub-industry with regards to 21 ecosystem services. The scores range from very high materiality to very low materiality. When provided with the scores, one is able to calculate the dependence and impact a company has on biodiversity based on the number of products and the location of the company’s production assets. Finally, with the help of balance sheet data from financial institutions, it is possible to determine the extent of lending to, and investment in, sectors with products that are dependent on a certain ecosystem or that extensively impact a certain ecosystem.

According to Banque de France, considering Scope 1 dependencies to ecosystem services (the dependencies of direct operations), 42% of the value of loans and investments held by French financial institutions are directed to companies that are highly or very highly dependent on at least one ecosystem service. According to DNB’s report, this number is 36% for Dutch financial institutions. Both reports indicate that the highest dependence is on the ecosystems that provide groundwater and surface water.

The Bank of England has also conducted a similar analysis considering the UK economy, and they found nearly three quarters (72%) of the stock of UK lending exhibits dependence on ecosystem services – levels that suggest elevated vulnerabilities to physical risks.

In terms of transition risk, the biodiversity impact of Dutch financial institutions is comparable with the loss of over 58.000km2 of pristine nature, an area of more than 1.7x the land surface of the Netherlands. In the case of France, the accumulated terrestrial biodiversity footprint of the French financial system is comparable to the loss of at least 130.000km2 of pristine nature.

* Please see attachment for hyperlinks.

Taking a closer look at sector exposure to biodiversity

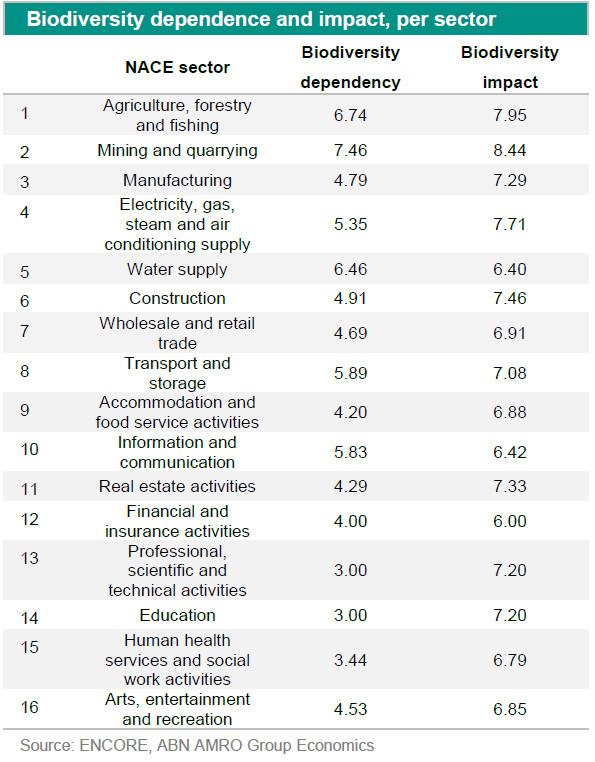

As we previously mentioned, the ENCORE database provides qualitative scores for sectors / sub-sectors to capture biodiversity risks. Even though this score is qualitative (very high materiality to very low materiality), we transform each score into a number between 1 and 10 in order to provide some quantification of each sector’s dependence / impact on biodiversity. Subsequently, we can also evaluate how much of a bank’s loan book exposed to biodiversity risks.

With the adoption of the Basel III framework, banks are now required to publish a regular Pillar 3 Report, where they display their loan book exposure by sector, according to NACE codes. As an interim step, we had to match 16 NACE sectors to the corresponding sub-sectors included in the ENCORE database 1). We then proceeded to calculate biodiversity dependence and impact per NACE sector by averaging all scores assigned by ENCORE to specific sub-sectors.

According to the table above, dependency scores range between 3.00 and 7.46. As expected, primary economic activities, such as mining or farming, depend a lot more on ecosystem services, than tertiary economic activities, like education or financial and insurance activities. For instance, the production of agricultural products relies a lot on the use of ground water, surface water, and animal pollination. While professional, scientific and technical activities, like research and consulting services, tend to depend a lot less directly on biodiversity, as the dependence of this sector is related to the buildings in which these activities take place, rather than the activity per se. Furthermore, it is easier for a consulting firm to change offices to a less-polluting building, than for a farmer to move a crop to a different place.

On the other hand, impact scores tend to be a lot higher across all NACE sectors, with scores ranging between 6.00 and 8.44. Even though tertiary activities do not depend a lot on ecosystem services, they tend to impact biodiversity through different channels. For instance, offices tend to produce a considerable amount of waste and non-recycling materials, as well as emit a large amount of non-GHG air pollutants.

After having computed the biodiversity scores of all NACE sectors, we proceeded to evaluate banks’ exposure to biodiversity-related risks, according to their loan books. Nevertheless, it is important to note a few caveats. First of all, the choice of transforming a qualitative score into a quantitative one, and the choice of the intervals, has inevitably introduced a certain degree of subjectivity in the results. Furthermore, the fact that the qualitative categories are quite broad reduces the granularity of the results. For instance, different companies within the same sector will have different scores, and even if all companies score “low risk”, that could still range between 2.8 and 4.6, such that, by averaging all scores, we lose the individuality of the different results.

Despite of these issues, we judge that this is a good starting point for better assessing biodiversity risks at the sector level. Biodiversity-related research is still an emerging field, but hopefully this could provide some interesting insights to build on further on.

Taking a closer look at the exposures of 17 European banks

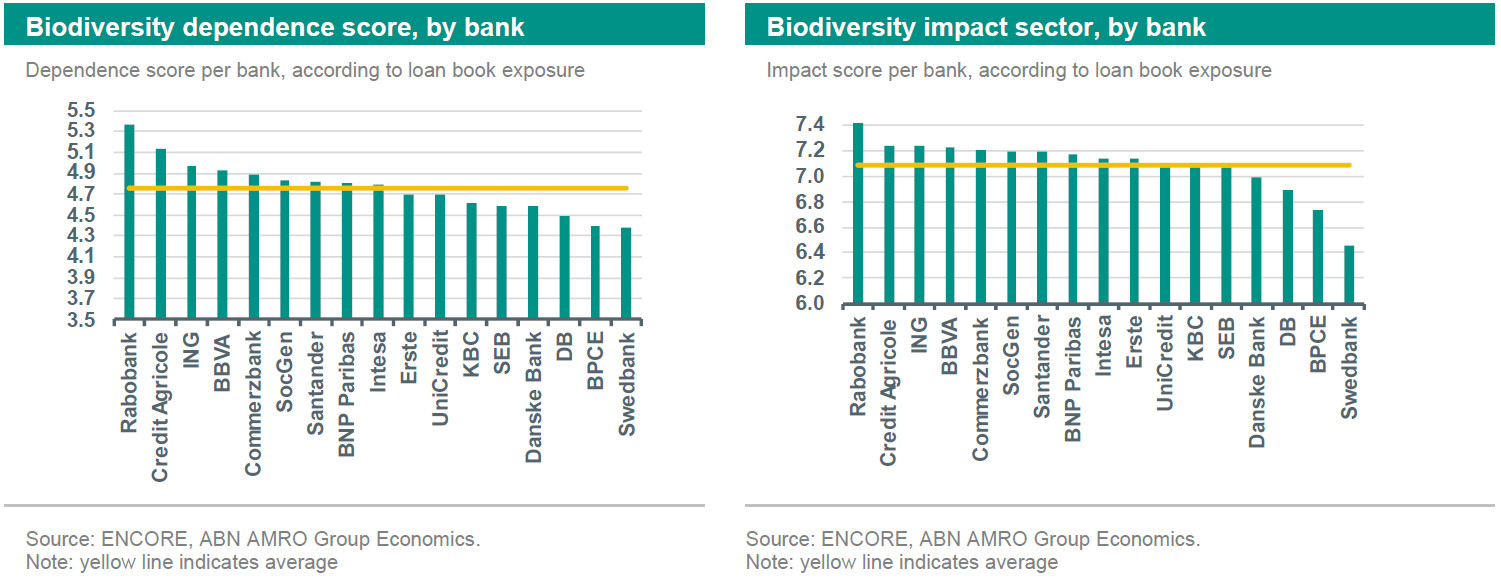

As a next step, we selected 17 European banks. These include a number of Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) and other large regional banks, from countries like Germany, France, Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Austria, Sweden, Belgium and Denmark. Once we obtained each NACE sector’s scores and each bank’s loan book exposure by sector, we calculated the weighted-average score of each bank’s biodiversity dependence and impact.

The graph below on the left shows each bank’s loan book dependence on biodiversity from largest to smallest. The dependence score provides insights on the physical risks that each bank is currently facing. The numbers range between 4.38 and 5.37, which shows that there are not very stark differences across banks. Seven out of the 17 banks studied present a below average dependency score – they are less exposed to physical risks than the remaining 10 banks.

On the other hand, the impact score (see chart on the right) provides an idea about how banks are exposed to transition risks. Were governments to introduce new measures, how would that impact banks? Here, the scores are less encouraging, ranging between 6.46 and 7.42. Once again, there are no major outliers, even though four banks score a result below average.

Nevertheless, we can take a closer look at the worst performer in our sample, Rabobank. Even though the bank’s scores are relatively close to those of the other banks, the Dutch bank is still the worst performer across the sample. This is largely influenced by the bank’s exposure to agriculture – a sector that besides depending a lot on, for instance, surface and ground water, also exerts a lot of pressure on the ecosystem around it (i.e. “herbicide and pesticide use for arable crops leads to substantial environmental population, particularly of nearby water bodies and soils”).

Credit Agricole registers the second highest (weakest) scores in both dimensions, right after Rabobank. In the case of the French bank, its largest exposures are to manufacturing and electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply. Even though these sectors do not score as badly as agriculture, they still exert a considerable impact on biodiversity. For instance, “the pipelines used to distribute gas have a significant spatial footprint, which can lead to habitat degradation and fragmentation throughout the pipelines’ life cycle”. Despite the poor scores, the bank has recently published a on biodiversity and natural capital. Which leads to the next important question: considering banks’ relatively weaker scores, are they addressing the topic? And if so, what are they doing?

How are banks addressing the issue?

Given how important it is to consider biodiversity risks stemming from bank’s loan books, it is worthwhile analysing how banks are approaching these risks in their Annual and Sustainability reports. To conduct such an analysis, we used Natural Language Processing (NLP) –a branch of computer science that leverages textual data (such as text from annual reports) to compute statistics and form interesting insights.

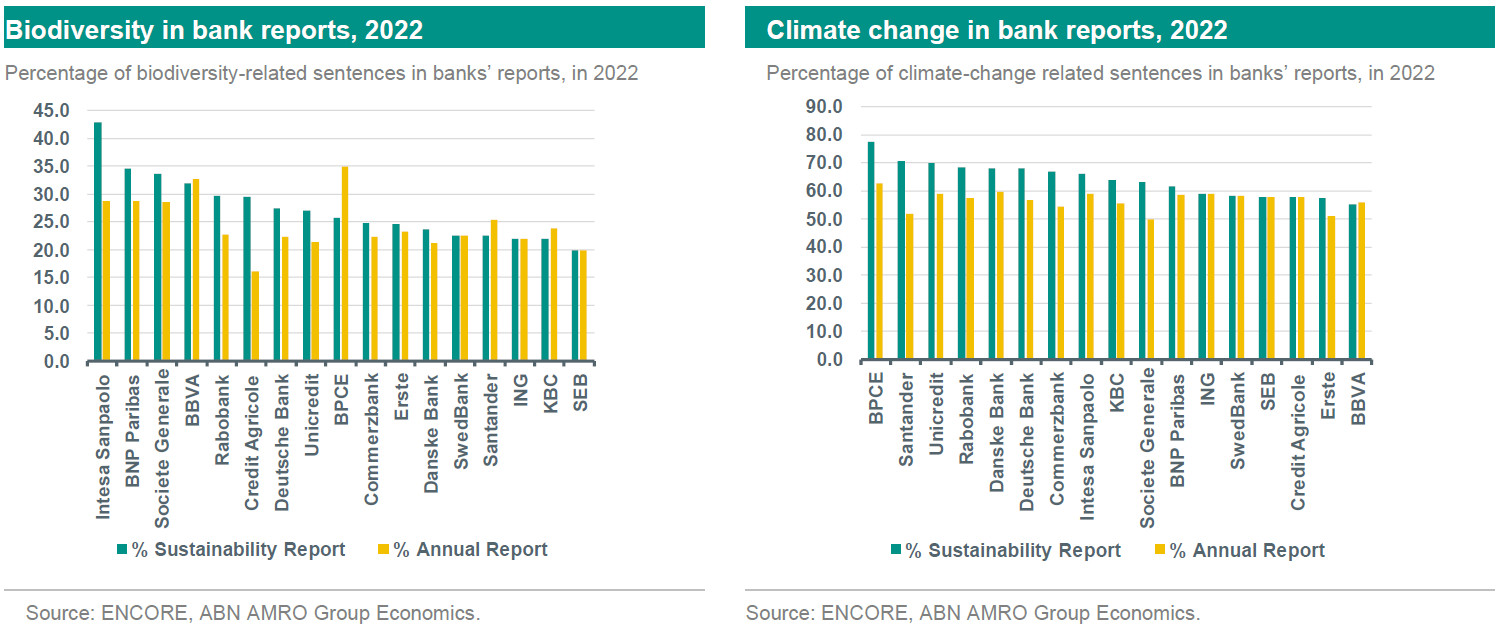

We analysed the annual and sustainability reports of the 17 banks that were published in 2022. The reports were first cleaned of unimportant words and symbols. Then, we defined a list of 188 terms related to climate change and 100 terms related to biodiversity. The idea was to scan the reports in different years and count the number of sentences including biodiversity or climate-change related terms, as a percentage of the total sentences in a report, in order to understand if banks were devoting attention to these topics.

According to our results, climate change is getting more attention from banks in their reports than the topic of biodiversity. Nevertheless, banks are also paying attention to the topic of biodiversity. Even though this theme is still at an infant stage, 30% of all sentences included in sustainability reports of 2022 regarded biodiversity. Not surprisingly, this number is higher for climate-change, close to 65%, due to the fact that the topic has been on top of regulators’ minds for longer.

In spite of that, banks might be underestimating the interaction between biodiversity and climate change. Biodiversity losses will exacerbate climate change risks, and vice-versa – the risks are not isolated. As such, paying less attention to one while targeting the other might prove unsuccessful and unsustainable.

Conclusion

Biodiversity loss is an important topic for companies and financial institutions to focus on from both a sustainability perspective but also a financial risk one. Despite still being at an infant stage, in terms of research, regulators across Europe have been developing methodologies to further improve our knowledge and understanding of the subject. By leveraging on the ENCORE database, we also tried to understand to what extent different sectors are exposed to biodiversity risks, and then calculate the relative exposure of 17 large European banks to biodiversity loss.

As expected, primary sectors, like agriculture and mining, are more exposed to physical risks, given their dependence on certain ecosystem services, like animal pollinators and ground water. On the other hand, sectors which are not as dependent as agriculture, like consulting services, are largely exposed to transition risks, due to their impact on biodiversity. For instance, offices in which consultants operate tend to produce a lot a of waste and emit large levels of nitrogen gases.

By combining each sector’s score with bank’s loan book, we were able to grasp banks’ exposure to biodiversity loss risks. Results showed that banks tend to have similar large exposures to both physical and transition risks, which raised the question about whether banks were paying enough attention to the topic. By using Natural Language Processing, we were able to assess if banks were approaching the topic in their annual and sustainability reports. Even though climate-change is getting relatively more attention than biodiversity, 30% of all sentences included regard biodiversity. So, yes, banks are definitely paying attention to the topic!

Nevertheless, there is still work to be done. The first challenge would be to improve the availability and quality of data. Despite the data provided by ENCORE constituting a very good first step, this data is still qualitative and lacking measurement units. Secondly, the complexity of the subject makes it challenging to define all possible shocks and the extent to which those shocks might affect the supply chain. As such, it would be of vital importance to have the several stakeholders, from non-financial firms to regulators, to partner and work together on the topic. This would not only prove essential for banks, but it would also benefit the conservation of biodiversity and preserve the services provided by ecosystems, to guarantee the longevity of life as we know it.

1) Please see the appendix in attachment for more details about the match between NACE and ENCORE sectors