ESG Strategist - Investors do not agree among themselves or with ESG rating agencies

More and more investors have been developing their own ESG rating methodologies. However, investors still lack a benchmark with which they can compare their own ratings. Except that offered by ESG rating providers. Investor doubts about ESG rating agency scores has been growing due to concerns about the accuracy and transparency of their methodologies.

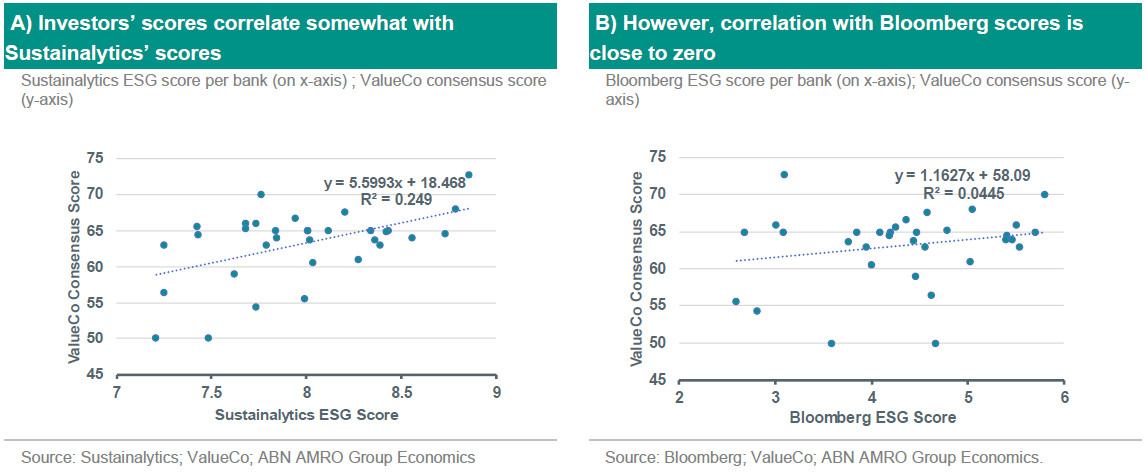

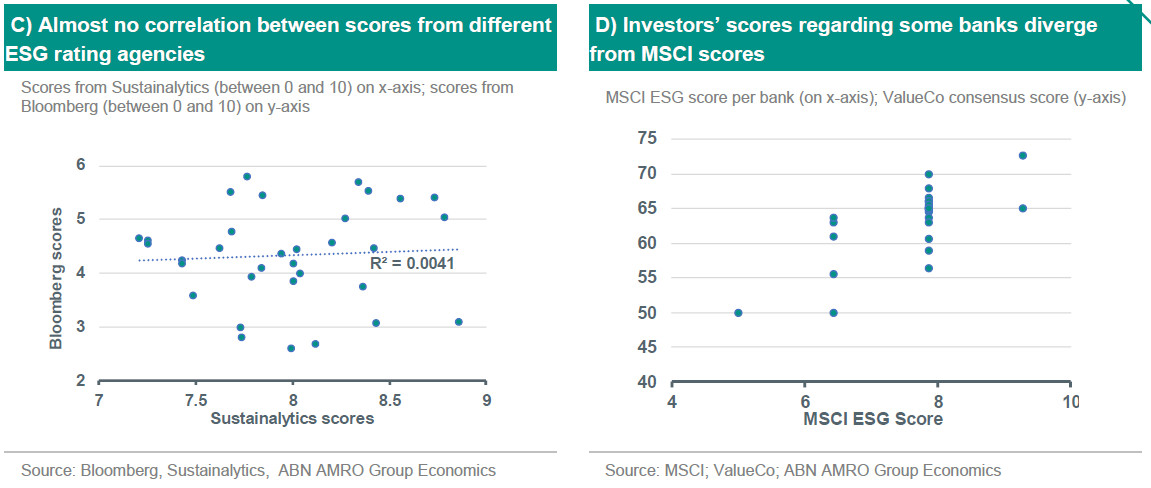

In this publication, we compare external and in-house ratings - collected and standardized by ValueCo - and discover that investors’ own scores are weakly related to Sustainalytics, but do not show any correlation with neither Bloomberg nor MSCI scores

Meanwhile, we also see quite some disparity between investors’ in-house scores, so investors do not seem to agree among themselves or with ESG rating agencies

The lack of a common understanding across investors and ESG rating agencies might be the reason why market pricing is not consistent

More and more investors have been developing their in-house ESG rating methodologies. This can be seen in the results of the latest ‘Rate the Raters’ report (see ) – a report that was first released in 2010 by the ERM Sustainability Institute, designed to influence and improve the quality and transparency of corporate sustainability ratings. In a survey question asking investors what the most common sources of ESG data that are used in decision making, 53% chose in-house research – a number that grew from 41% in 2022. However, it is still hard for investors to compare their analysis to those of their peers, as there is no clear benchmark – apart from that offered by ESG rating agencies.

At the same time, doubts about the ratings provided by the ESG agencies has been growing in recent years. For instance, the Rate the Raters report indicated that “most surveyed investors have only modest confidence that ESG ratings accurately reflect sustainability performance, with a sizeable minority of corporates feel they do not”. Some of the reasons noted by investors regard the lack of quality and transparency of the data, and the lack of comparability between different ESG rating agencies. Nevertheless, 57% of investors still rely on ESG rating agencies to supplement their organization’s ESG research. Indeed, the report notes that “investors do use external ESG ratings and data when making investment decisions, even as they struggle to make sense of raters’ data irregularities and questionable methodological approaches”.

In this piece, we investigate whether investors’ internal scores are aligned with those provided by ESG rating agencies. And for that, we use data from ValueCo. ValueCo collects and standardizes investors’ proprietary sustainability- related scores, and calculates a consensus score, which equals the median of all investor scores. Additionally, it also computes a consensus strength, which shows to what extent investors agree with each other.

Our sample

In this piece we focus solely on global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and other large regional banks across the EU and the UK. Our sample contains 33 banks, from 14 different jurisdictions. As not all banks are being rated by all investors, we have only included banks that have a minimum of 10 responses in our sample. Furthermore, each bank must have an ESG rating provided by Sustainalytics, Bloomberg and MSCI. Sustainalytics scores range between 0 and 100, and the lower the score, the better the performance of the rated entity. However, for Bloomberg, scores range between 0 and 10, with a score of 10 indicating a very good performance. Hence, we first divided Sustainalytics’ scores by 10, and then subtracted each score to 10 in order to get a score similar to that of Bloomberg. The publicly available scores from MSCI are qualitative, such that we had to convert them into numerical scores. Fortunately, MSCI shares the intervals to which each qualitative score corresponds. For example, a score AAA corresponds to an ESG score between 8.57 and 10. In this case, we computed the median of the intervals and matched each qualitative score to the median of its interval.

As we can see in the graph below on the left, ValueCo scores are weakly correlated with Sustainalytics scores. By plotting a trendline between both variables, we can see that the equation’s R-squared equals 0.298, which means that the regression explains close to 30% of ValueCo scores. That is, there is some modest agreement between the consensus of investors and Sustainalytics’ views in judging the ESG credentials of various banks.

This cannot be said with regards to the other public scores. When comparing Bloomberg ESG scores with the consensus of investor scores, the R-squared is considerably low, less than 1%, which means that there is basically a zero correlation between Bloomberg scores and ValueCo scores. This is not surprising given that Sustainalytics scores are also not correlated to Bloomberg scores, as we show in graph C) below. One reason that might help explain why investors are not relying as much in Bloomberg scores could be related to Bloomberg’s scoring being in its relative infancy, with Sustainalytics having a longer track record. For instance, while Sustainalytics has been in the business for almost 15 years, Bloomberg ESG scores were only introduced in 2020. Furthermore, according to the latest report of Rate the Raters, investors rank Sustainalytics in third place with regards to both the quality and usefulness of the its ratings services, while Bloomberg ranks in eighth place.

Finally, if we compare MSCI scores with ValueCo scores, the results are a bit different when compared with the other two providers. Because different banks share the same qualitative score (e.g. AAA), and were matched with the median of the respective interval, there are bundles of banks sharing the same quantitative score. However, what is interesting, it that, even if rated the same by MSCI, those scores are often very different to the internal scores of investors. For instance, if we focus on banks with a rating AA, we get to a total of 18 banks. But across this bundle, there are banks which, according to investors, score 55, and others which score 70 – proving once again the lack of a common view with regards to ESG scoring.

The difference between the estimated and the actual values

From the results plotted above, and focusing solely on Sustainalytics’ results – given that, from the three ESG providers, it presented the best fit with investors’ scores – we would like to dig deeper into the outliers. While some banks do show scores similar to those estimated by the equation in Sustainalytics’ graph, that is often not the case – those are the so-called outliers. Perhaps, in the case of being an outlier, it may be that the consensus strength (i.e. how much investors agree on the ESG score of an issuer) is also low.

In the graph below, we plot the different ESG scores that 13 of the 33 banks received from different investors as contributing to ValueCo data. Interestingly enough, one of the banks registering the largest deviation from the trendline is also one of the banks with the highest consensus strength, namely Unicaja. Furthermore, Bank of Ireland, despite having an error of 7, also shows a high consensus strength of 76. As such, it seems that large discrepancies between the trendline and outliers are not supported by low consensus strengths. Hence, investors seem to agree among themselves regarding some banks, yet still disagree with Sustainalytics on the ESG performance of a bank.

Another good example is Mediobanca. The Italian bank ranks similar scores from both ValueCo and Sustainalytics. However, contrarily to its peers above, the consensus strength of this bank is as low as 58. While some investors score the bank with a ESG rating of 13 (out of 100), others score it an 85. This shows once again the detachment between ValueCo’s and ESG rating agencies’ scores.

These results suggest a lack of a common assessment of many bank’s ESG credentials across investors and ESG rating agencies. If on the one hand, investors might share the same opinion about a bank’s ESG performance, this might be completely mis-aligned with Sustainalytics’ opinion, or the other way around: investors might agree with Sustainalytics, but completely disagree among themselves. This might also be the reason why market pricing is not consistent, and the so-called “greenium” is often not a coherent feature across various fixed income asset classes.

Going forward

Some steps were already taken at the European level in order boost investor confidence in ESG rating agencies. On 20 December 2023, and after some changes to the first draft proposal, the Council agreed (see ) that ESG rating providers will need to be authorised and supervised by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and comply with transparency requirements, in particular with regard to their methodology and sources of information. Nevertheless, there will be a lighter transition period of three years for existing small ESG rating providers and new small markets entrants. The next step regards interinstitutional negotiations, which already started in January 2024.