ESG Strategist - Large biodiversity investment gap

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) characterizes nature-based solutions (NbS) as “initiatives designed to protect, conserve, restore, and sustainably manage ecosystems”. Examples of these solutions include ecosystem restoration, urban green spaces, and sustainable land management. In the EU, the integration of nature-based solutions across diverse landscapes is deemed crucial for fulfilling the ecosystem restoration objectives outlined in the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Additionally, NbS are considered vital for achieving climate change mitigation goals. Since the establishment of the Global Biodiversity Framework in Montreal in December 2022, there has been a slight increase in financial inflows towards nature preservation and restoration. Nevertheless, these remain substantially below the trajectory required to meet the targets set in Montreal. For the first time, the report identifies that there are USD 7 trillion of financial flows (public and private) that finance activities that have a negative impact on nature. These activities include price incentives and fiscal transfers to the agriculture sector, consumption subsidies for fossil fuels, and support for fishing capacity that exceeds the maximum sustainable yield of fish stocks. These figures could potentially be underestimated as they account only for direct impacts. Despite the substantial investment potential of NbS, the most effective measure to halt and reverse nature loss is the redirection of nature-negative financial flows. While increased public finance for NbS is crucial, more efforts would also be need to repurpose harmful subsidies if biodiversity goals are to be met. Simultaneously, governments would need to establish regulations and economic incentives to redirect private financial flows away from activities that are harmful to nature and towards nature-based solutions. In this note, we aim to explore the state of NbS, examine their financing trends over recent years, and discuss strategies to enhance investment in nature.

Nature-based solutions (NbS) are initiatives designed to protect, conserve, restore, and sustainably manage ecosystems

UNEP highlights that NbS remain severely underfunded, with current finance flows amounting to USD 200bn, falling short of the USD 543bn needed by 2030

Of the current financing, public finance remains the main source of finance at 82 per cent of the total

Measures to foster private investment should include: the growing understanding of the impacts and dependencies on nature, improving government regulation, increasing recourse to blended finance, among others

The gap between investment needs and current expenditure

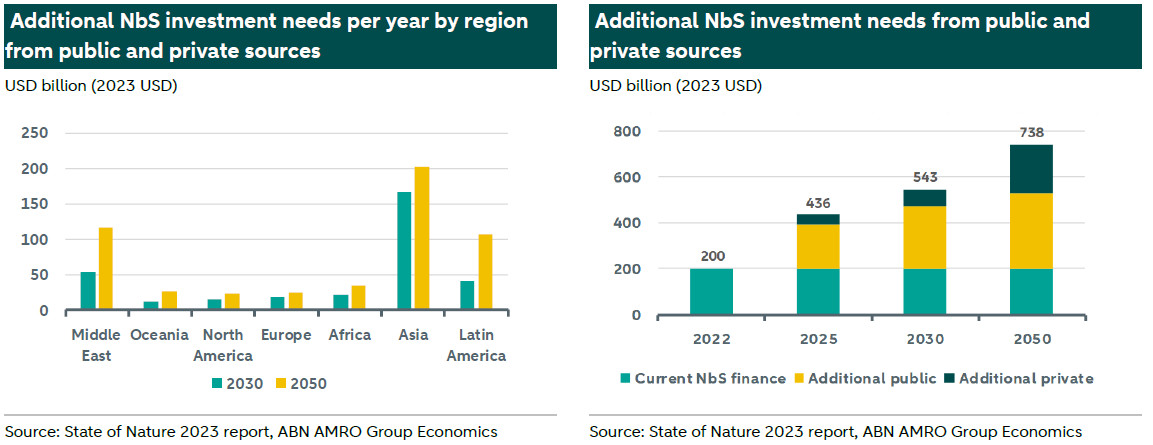

Annual finance flows to NbS in 2022 were roughly USD 200bn, considerably below the amount needed by 2030, which is currently estimated to be around USD 543 bn. Of the current financing, public finance remains the main source of finance at 82% (USD 165 bn), while private finance remains modest at USD 35bn (18% of total finance flows to NbS). Moreover, of the latter, 33% is channelled through biodiversity offsets and credits, which some researchers suggest that do not incentivize companies to actually reduce their own biodiversity impact.

In order to close the gap between investment needs and current financing, annual financial flows to NbS need to more than double by 2025 (from USD 200bn in 2022 to USD 436 bn) and nearly triple to USD 543bn by 2030 to reach climate, biodiversity and land degradation targets.

Moreover, to better target finance flows, the report looks at the regional distribution of investment needs. According to UNEP model, the numbers suggest that investment needs are likely to be greatest in Asia with an additional USD 167bn per year by 2030, rising to USD 203bn per year by 2050, and the Middle East and Latin America are also expected to need relatively high levels of NbS finance. However, it is important to emphasize that while these regions have the highest financing needs—due in part to their being home to some of the world's largest forests—this does not necessarily imply they should bear sole responsibility for funding these efforts. Given the global dispersion of supply chains, economic activities worldwide impact what occurs in these regions, such as Brazil, which houses the Amazon rainforest. Thus, a case could be made that the responsibility for financing NbS should be shared globally across all continents. This is especially pertinent considering that many of the most affected countries are also among the poorest.

Who will finance the required investment in nature-based solutions?

In recent years, there has been a significant push for the private sector to increase funding for biodiversity, restoration, and climate action. This push is largely motivated by the perceived constraints on governments’ capacity to boost direct public investment, due to the challenging state of public finances in many cases. In response, some research has examined the business case for private investment and has identified key limitations, underscoring the continued strong case for public investment in public goods. The graph above on the right illustrates the annual additional NbS finance needed from both public and private sources. While both public and private finance flows for NbS are anticipated to rise steadily until 2050, private sources are expected to account for a growing proportion of the total NbS finance, increasing from the current 18% to 33% by 2050. However, given the magnitude of investment required and the nature of NbS, public investment will remain vital and should increase threefold from current levels to USD 439 billion per year by 2030.

Why is private investment so much lower?

Investing in nature-based solutions (NbS) presents several challenges that can limit uptake by private actors. These include the high opportunity cost of land, elevated country risk in countries with significant NbS potential, high transaction costs, and the public goods nature of many ecosystem services offered by NbS. Nevertheless, there are valuable lessons to be learned from climate finance. Although climate finance remains insufficient to fully realize mitigation and adaptation targets, substantial public investment and incentives have successfully catalysed private climate finance. Thus, the critical question becomes: how could private investment be directed towards nature-based solutions?

Firstly, businesses and financial institutions would need to increasingly recognize the importance of understanding their impacts and dependencies on nature. This awareness provides an opportunity to invest in sustainable supply chains, which can enhance resilience and promote long-term success. Large businesses and financial institutions have the leverage to influence suppliers and producers, encouraging them to adhere to certification and sustainability standards that guide efforts towards more environmentally friendly practices.

Taxonomies, like the EU Green Taxonomy, have been developed to identify green activities, but they primarily focus on climate-related aspects such as mitigation and adaptation. These frameworks do not adequately address Nature-based Solutions (NbS) or broader nature impacts. While negative climate impacts can be assessed by looking at emissions intensity, quantifying effects on nature is more complex due to the multifaceted interactions and dependencies involved.

To address this complexity, it is crucial for businesses to advocate for governmental action in developing comprehensive frameworks and tools that can effectively measure nature impacts, dependencies, and risks. Such tools would enable businesses to make informed decisions that better integrate sustainability into their operations and contribute to the preservation of natural ecosystems.

Secondly, government regulation can serve as a powerful mechanism when private sector action is crucial. Regulations that require biodiversity offsetting– measurable conservation outcomes resulting from actions intended to compensate for significant residual biodiversity loss from development projects - have stimulated private sector investment in biodiversity conservation and restoration initiatives in several countries, including Australia and France.

Thirdly, governments can incentivize private investment by lowering costs and/or risks for private entities through blended finance instruments. For instance, using public capital (domestic public funding or Official Development Assistance) for concessional and subordinate loans, credit guarantees, and grants can catalyse private investment in activities that investors might otherwise find too risky or unfamiliar. It is more efficient to leverage existing structures, as developing new blended finance frameworks requires time. Scaling blended finance can be facilitated by establishing leaner governance structures.

A significant barrier to private investment in some NbS projects has been the absence of consistent and monetizable revenue streams. The emergence of carbon revenues has, in certain cases, made investment in restoration and sustainable land management financially viable. This is particularly crucial for covering costs or compensating for lost productivity as food systems transition from extractive monoculture to regenerative agricultural systems.

Lastly, NbS possess characteristics that hinder private investment. As previously mentioned, the public goods nature of the services they provide is one barrier. Further challenges include the tendency for NbS projects to be small and complex, with long investment horizons, a lack of early-stage financing, and susceptibility to regulatory uncertainty. The lack of standardization of NbS as an asset class makes it less appealing for institutional money managers with strict mandates. Consequently, financing is challenging, and innovation and further development of financing structures and products are essential. Many NbS projects in the EU, for example, are financed through a combination of different products based on large debt issuances from multiple backers. Tailored structures work best for NbS because they can integrate various funding, financing, and revenue streams for different project components.

In summary, a major transformation is imperative

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are vital for advancing sustainable development and tackling global environmental challenges, including biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions stabilization, with an urgent and entirely feasible need to scale up finance and implementation efforts.

Consequently, governments should prioritize public funding for public goods like nature. However, private investors also hold a key responsibility in fulfilling investment requirements and achieving nature protection goals. Strategies to stimulate private finance flows towards sustainable land management and restoration include government incentives and regulation. Moreover, expanding innovative financial instruments, such as green bonds and blended finance funds, can support the scaling of private initiatives necessary to meet the Rio targets.