Global Monthly - Are we past the worst with tariffs?

The US-China trade truce shows that there are limits in how far the Trump administration is prepared go in implementing its radical trade agenda. We expect significant tariffs to remain in place, and this will weigh on growth in the near term. However, the trough in growth is likely to be shallower, and the downside risks significantly reduced. We lay out our forecast changes on the back of recent developments. Spotlight: Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill is highly regressive, puts upward pressure on bond yields, and risks amplifying economic downturns.

Global View: Tariff uncertainty seemingly finds a bottom, but the damage is still significant

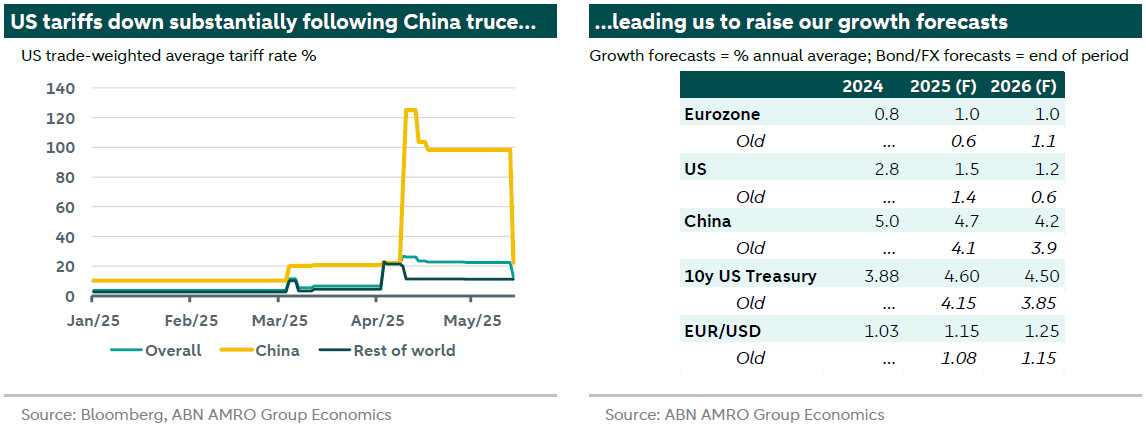

For a very worrying moment, it felt like the sky might be the limit for US import tariffs. After a relentless escalation in the US-China tariff war, both sides stepped back from the brink – to the collective sigh of relief of the global economy. To be clear: US import tariffs are likely to remain much higher than before the 2nd Trump presidency (unprecedented in modern times), and the shock to global trade will likely still be significant. Even with trade deals to avoid even higher tariffs, we expect the 10% universal baseline tariff on US imports to stay, alongside higher rates for specific sectors like cars (with quotas at lower rates, similar to the US deal with the UK). Moreover, policy uncertainty will continue to be a significant drag on the global economy. But if there is one important thing we learned over the past month, it’s that there are limits to how far the US administration is prepared to go in implementing its radical trade agenda. This puts a floor under how far the global economy can fall on the back of this. What has also become apparent is that businesses are finding various ways to avoid the tariffs, whether it’s making use of previously in US customs regulation, setting up in the US, to using leasing structures for instance on . This, too, helps to soften the blow to activity from US tariffs. Taking all of this together, and even considering the latest threats by the US to put a 50% tariff on EU imports, we have substantially raised our growth forecasts across the US, the eurozone and China (see summary table below; for quarterly forecasts see the table at the back of this publication). In the very near term, growth is still expected to slow on the back of higher tariffs, but the trough is likely shallower, with reduced downside risks to the outlook than we thought previously.

What does Trump’s 50% tariff threat against the EU mean for the eurozone outlook?

Late last Friday, president Trump threatened a 50% tariff on EU imports to be imposed on 1 June, but by the end of the weekend he announced a delay to 9 July (the original deadline for countries to sign trade deals with the US or else face higher tariffs). A 50% tariff would be substantially more damaging than the previously threatened 20% tariff, and for most products would probably entail EU exports to the US falling to near zero. If sustained indefinitely, this could well tip the eurozone into a recession. However, even if the 50% tariff were to be imposed, the experience of the US-China tariff war teaches us that it would be highly unlikely to stay in place for long. Such a prohibitive tariff would also be very damaging to the US economy, and this is before EU retaliation is factored into the equation. Given this and given Trump’s subsequent delay to allow time for US-EU negotiations, we do not factor a 50% tariff into our base case. Our base case assumes the EU will forge a deal with the US that in all likelihood resembles the deal the US struck with the UK.

GDP growth forecasts: Eurozone & China revised substantially higher in 2025; US more in 2026

Assuming deals that keep US tariffs broadly as they are, we expect underlying growth to slow across the global economy in the near-term before picking up in late 2025 and into 2026. In the US, headline GDP growth will see a boost in Q2 from the unwinding of trade frontloading, but underlying demand (investment and consumption) is expected to slow, and to stay weak into Q3. In the eurozone and China, the hit to US-bound exports is expected to offset the nascent recovery in domestic demand (itself threatened by high uncertainty), though that shock is expected to be less pronounced than we thought previously. In terms of the changes to annual average forecasts, we have substantially raised our 2025 growth forecasts for the eurozone and China (+0.4pp and +0.6pp respectively), with smaller changes in 2026 (-0.1pp in the eurozone, +0.3pp in China). For the US, we expect the inflation hit to real incomes to be less severe and long-lasting than previously. The end of 2025 will therefore see a milder downturn and 2026 a more rapid recovery. This results in a small upgrade to our 2025 forecast (+0.1pp to 1.5%) and a larger upgrade to our 2026 growth forecast (+0.6pp to 1.2%).

Fed & ECB, bond yield and FX forecast changes: An extra Fed cut, Treasury yields up, dollar down

Our ECB view is unchanged, with the Governing Council still expected to lower the deposit rate by a further 75bp over the coming meetings to 1.5% by September. While the growth shock in the eurozone is somewhat milder, inflation is still expected to substantially undershoot the ECB’s 2% target later in the year, and the Governing Council seems to have come around to this view. For the Fed, we now expect rate cuts to start a little sooner – in Q2 26 instead of Q3 26 – helped by a somewhat lower peak in inflation. However, we still see the scope for rate cuts as limited given the tariff risk to inflation.

What does all of this mean for bond markets? Our German bund yield forecasts are broadly unchanged. For the US, it is a different story. Despite the additional Fed easing that we expect, we are substantially raising our US Treasury yield forecasts. For the 10y, we now expect yields to end the year a bit above current levels at 4.60% (previous: 4.15%), and we now expect only a small decline next year to 4.50% (previous: 3.85%). This change is largely due to the significant rise in term premium, i.e. the compensation investors demand for holding bonds with longer maturities. Term premium has risen significantly in recent months and is expected to remain elevated, on investor worry over large US budget deficits and hence rising issuance in an environment of lacklustre demand for US Treasuries. The recent passage by the House of the new tax cut bill – something we look at in our Spotlight this month – is a key driver of this.

Higher term premia in the US are not supportive for the dollar, and we have made downgrades across the board to our USD forecasts. We now expect EUR/USD to end 2025 at 1.15 (was 1.08), and for the pair to appreciate to 1.25 2026 (was 1.15).

June will be eventful, and is likely to bring some more clarity to the outlook

Ahead of the quieter summer period, prepare for a busy and possibly volatile June. As we approach the 9 July deadline for the US reciprocal tariff pause, negotiations are likely to heat up and we are bound to see some more cliff-hanger tweets that roil markets. Japan has said it is aiming to seal a deal with the US by the 15-17 June G7 summit in Canada. For the EU, it is likely to want to wrap up its trade deal with the US in order to have more cordial EU-US relations at the NATO summit in The Hague on 24-25 June. Meanwhile, the NATO summit itself should help resolve uncertainty about another key driver of the outlook in Europe: defence spending. Early indications are that the defence spending target will be more than doubled to 5% of GDP from 2%, with a core defence spending target of 3.5%, and 1.5% devoted to cyber security and infrastructure that the military depends on. Given that a number of EU countries still fall short of the 2% target, a key factor to watch will be how soon member states will be obliged to meet the ambitious new target (most likely over 7 years), and whether there are any interim targets. We expect defence spending to be raised substantially over the coming two years, though likely with wide variations across countries given the differences in fiscal capacity and political urgency. Germany is likely to spearhead spending, while Spain and Italy are likely to be laggards. After the NATO summit, we should start to see more concrete plans from governments on the composition and timing of spending over the coming years.

Spotlight: Beyond the Budget of the Big Beautiful Bill

Rogier Quaedvlieg - Senior Economist US

Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill is likely to be passed, if in a slightly modified version.

Beyond the reckless increase in government deficit implied by the bill, the details show a highly regressive tax policy, with a direct transfer from the poorest to highest income households.

The bill significantly increases the risk of government yields rising, and risks amplifying economic downturns by diminishing what little safety net the US had.

Our initial take on the new bill was provided here.

Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill passed the house last week and is on the way for approval - after further to be determined modifications - to the Senate. Even though details are not yet set in stone, the budget implications are clear and immense. This bill costs more than $4 trillion, around $3 trillion of which is unfunded. If ‘temporary’ tax cuts are made permanent, $5 trillion of extra debt will be added over the next 10 years. To put that into context, the Inflation Reduction act cost half a trillion dollars, entirely funded by tax increases. The Affordable Care Act cost $1 trillion over 10 years, entirely funded. Trump’s 2017 TCJA, which this bill makes permanent, left an estimated $1.5 trillion unpaid for.

What does the American taxpayer get back for this? Most people will get a tax cut compared to a scenario in which the 2017 TCJA tax cuts would expire, even if not compared to current policy. The proposed tax cut is highly regressive. The Tax Policy Center estimates that 2/3rd of the dollar value of tax cuts goes to the top quintile of earners, a quarter of the tax cuts goes to the top 1%. Low income households pay the price of this in multiple ways, predominantly to cuts in Medicaid and food stamps. It is estimated that through changes in the requirements for Medicaid, 13 million people will lose their health insurance, ‘saving’ the US taxpayer $1.1 trillion. The bill also cuts $300 billion on food stamp programs. Implementation dates have been set to 2029 for now, such that voters will only notice the impact of these policies under the next administration. On the plus side, there are also tax exemptions on tips and overtime, and there are extended child credits. However, the details cast some doubts on the ability of these measures to reach those who need it most.

The bill also cuts tax credits that support the energy transition, such as credits to wind, solar, electric vehicles and even nuclear power industries, winding down most of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) policies. This fits in the broader industrial policy agenda of the Trump administration of keeping competitors out of the local market through tariffs rather than the IRA approach of supporting the US’ industry to make it globally competitive. This hands the transition industry to China, to the extent that they did not already dominate it.

Treasury Secretary Bessent has stated he thinks government policy will supercharge the economy to grow out of this extra debt. This seems highly unlikely for two reasons. First, there might be some positive demand effect from these tax cuts, but the impulse is severely limited by the fact that this is an extension of current tax rates that would otherwise be raised. Most consumers will not be better off than they are right now. Second, growth would have to outpace real interest rates to even be able to run a deficit whilst keeping debt-to-GDP levels stable. Given other policy by the administration, nominal rates are unlikely to come down any time soon, while real rates may actually come down significantly thanks to tariff-induced inflation. Even if real rates turn negative, they are unlikely to turn sufficiently negative to run a 9% deficit without increasing debt-to-GDP levels.

Indeed, earlier policy choices made by this administration amplify the effects of the bill and vice versa. At the micro level, this bill hits households that are already the hardest hit by tariff-induced inflation and uncertainty over the past months. It cuts strongly into what little safety net the US had, at a time when the lowest income households are struggling to get by, cutting their consumption further. These cuts fund tax cuts to the households who are not really facing any such constraints (and are therefore also unlikely to provide a growth impulse). With this bill, and previous DOGE cuts, the impact of losing your job will be much higher, amplifying the impact of a downturn in the economy. Even middle income households will likely see adverse effects through higher mortgage and auto loan rates, which are often directly tied to long-term government yields.

Indeed, on that more macro level, the bill adds trillions of dollars to the debt right at a time where investors are already having second thoughts about US debt. The debt-to-GDP level currently stands at about 100%, and the current proposal increases the projected 2034 level from 117% to 129%. Bond markets have been shaky and volatile in response to recent government policy, and long-term rates have been rising, and will continue to face elevated risk premia, as reflected in our new forecasts. This seems like a particularly poorly timed moment to throw all fiscal caution to the wind. US debt was already a slowly ticking time bomb, but erratic, sometimes simply destructive, government policy, and a significant worsening of the fiscal trajectory through this tax bill significantly exacerbate the problems, bringing us closer to the tipping point where markets will no longer accept it.