Global Outlook 2026 - Eurozone: External environment rough, will Europe step up?

The eurozone economy performed well in 2025, despite the headwinds from US tariffs and intense competition from China – even if that performance is exaggerated by outlier Ireland. We expect growth to re-accelerate in 2026 as German fiscal spending ramps up, though southern European outperformance is expected to wane on the end of the EU’s Recovery & Resilience Facility. The ECB is expected to stay on hold through 2026-7. Near term risks are tilted to another cut given the looming inflation undershoot, but those risks could tilt towards a hike as 2027 develops.

Despite the many headwinds, 2025 has been a year of resilience and hope for the eurozone economy. US tariffs have left their mark, and will continue to do so next year in the form of weak export growth. Meanwhile, the eurozone continues to face intense competitive pressures from a China which has gone from being a major source of demand, to – increasingly – eating Europe’s lunch. Yet, despite the US tariff shock, the eurozone comfortably dodged a recession, and has so far defied expectations for a bigger slowdown: following the upside surprise in Q3 GDP, we now expect the economy to have grown 1.4% in 2025. Looking ahead, the ramp-up in German fiscal spending, alongside improving domestic demand (helped by ECB rate cuts) should see growth accelerate in 2026.

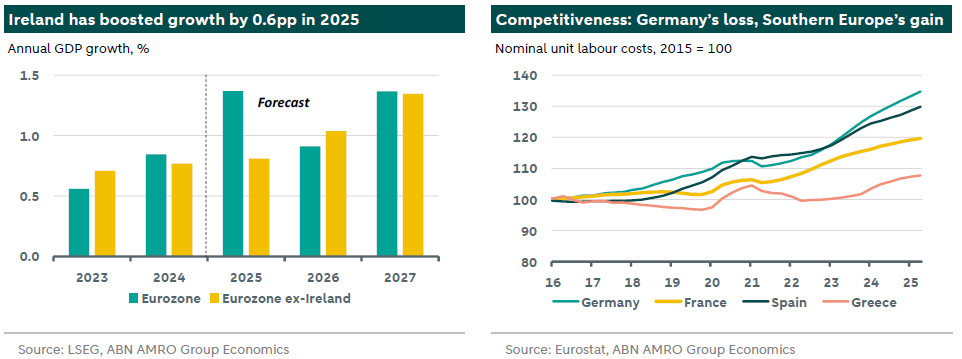

Still, in the near-term there remain downside risks to the outlook. Ireland, ever the thorn in a eurozone economist’s side, contributed a massive 0.6pp to 2025 growth so far. Put another way, eurozone growth would have been a much less impressive 0.8% in 2025 were it not for Ireland. Ireland was one of the chief beneficiaries of the spike in exports to the US ahead of the tariffs in April, but what has surprised is how gradual the post-tariff unwind has been, and how little this has impacted growth. The risk remains of a more substantial pullback in Ireland that could hit eurozone growth in Q4.

While some of this year’s growth may have been a mirage (Ireland’s GDP surges are often corporate tax planning balance sheet transfers), there has been some genuine strength this year. First, the periphery continues to outperform the core – particularly Spain, which continues to grow at a well above trend pace (our forecast: 2.8% in 2025). Continued Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) disbursements have helped, but there is also real underlying strength in southern Europe. Part of this is that southern European countries have been better positioned to benefit from the sectors seeing the strongest growth – namely tourism, and services more broadly. Second, we think improved regional competitiveness has a role to play. For years, these countries underwent an ‘internal devaluation’ following the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, i.e. wages were held down while they surged in northern Europe (in Germany and the Netherlands in particular). This factor may also yet help France dig itself out of a fiscal hole (see ).

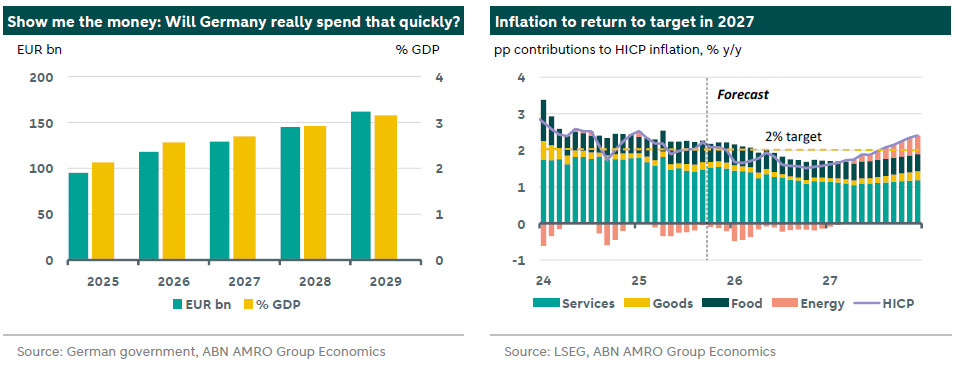

The strength in southern Europe has been a crucial offset to the weakness in Germany, which – even against our cautious expectations – has performed poorly this year. Despite the mid-year surge in optimism driven by frontloading benefits and the anticipation of increased fiscal spending under the newly appointed Chancellor Friedrich Merz, recent sentiment has shifted negatively. This change is attributed to further worsening of industrial production, currently at 2005 levels, alongside stagnant output in Q3 following a 0.2% quarter-on-quarter contraction in Q2. Given how much of a drag Germany has been on the rest of the eurozone, key going forward is going to be how quickly the German government rolls out its ambitious defence and infrastructure spending, but equally important is how the economy responds. For the longest time, Germany has suffered from a tight labour market and, more recently, high energy costs. But with the car industry undergoing a painful restructuring, slack is being gradually released. Whether that slack can quickly retool to meet the demands of higher defence and infrastructure spending remains an open question. If the German economy proves flexible, growth could surprise to the upside. If it does not, more of that spending will leak out in the form of higher imports, or – worse – the extra spending might be inflationary.

What about defence spending in other eurozone countries? We have long argued that most either lack the political will (southern Europe) or face major fiscal constraints (France) to raise defence spending significantly. Some are drawing on the EU’s EUR150bn SAFE plan, though most of those funds (around 2/3) are going to countries near the Russian border in central and eastern Europe. Some fiscally constrained western European countries will also receive significant sums (Portugal: 2.4% of GDP, Belgium: 1.6%, Italy: 0.8%, France: 0.6%). This, alongside spillovers from German (and possibly Dutch) spending will give some lift to economic growth in these countries. But in the very near term, much of the rise in defence spending will likely leak out in the form of higher imports. For this reason – alongside global competitiveness challenges – we expect net exports to remain a drag on GDP growth, even after the impact of US tariffs has faded.

Another growth driver to watch next year is the end of the EUR650bn Recovery and Resilience Facility. Just 57% of the funds have been utilised since the RRF started in mid-2021 and the deadline for disbursement is 31 August 2026. There is likely to be a rush of spending ahead of that deadline with probably some leniency for projects under construction/in progress. Thereafter, growth in the periphery is likely to slow as that spending dries up again, and this explains the quarterly growth dip that we expect in early 2027. The remainder of the funds – EUR283bn (c1.8% of eurozone GDP) could theoretically be repurposed for defence or other European spending goals. This is likely to be a discussion point among EU leaders as the RRF approaches its conclusion.

Against the backdrop of a broadly balanced growth outlook, inflation in the near term is set to undershoot the ECB’s 2% target, although this is largely driven by energy (and to a lesser extent the stronger euro), with core inflation expected to hold broadly steady. Indeed, by 2027 we expect inflation to move back to target once the energy drag fades, and there could be further upward pressure on inflation from the implementation of ETS2 (which could yet be watered down or delayed), as well as from German fiscal spending. The ECB has continued to communicate that it is in a ‘good place’ with regards to interest rates, though President Lagarde augmented this at the October Governing Council meeting with the caveat that it is not in a ‘fixed place’. Our base case sees the ECB keeping policy on hold until end-2027. With near-term risks to inflation tilted somewhat to the downside – given the oil supply glut, and our expectation for a further strengthening in the euro – the risk in the near term is more tilted to a cut than a hike. However, further out in our forecast horizon this balance of risks could start to shift more towards a hike.

Politics will also continue to be a key driver of the eurozone outlook. While not in the eurozone, Hungary’s general election in April could be a pivotal moment for the EU, given that PM Orban is currently trailing in the polls, and given his historic obstruction of many EU initiatives. A more pro-EU government there – coming alongside a new pro-EU Dutch government (topic 5) – could give new momentum to integration initiatives such as completing the capital markets union, the multi-annual budget or even Eurobonds (see this month’s special). Further ahead, the signs are less positive, with the French presidential election in 2027 potentially heralding a far-right presidency. While much can happen between now and then, centrists and those on the left are currently on the back foot politically in France. This will make dealing with France’s deficit problem in a growth-friendly manner all the more crucial, but on that we are not optimistic (topic 4).