Global trade - Frontloading precedes tariff shock

The recovery of global trade and industry seen in early 2025 was helped by trade frontloading in the run-up to higher US import tariffs. Calm before the storm? US import tariff shock will hit global trade, with container bookings into/from US already nosediving, export PMIs falling sharply and IMF and WTO cutting their world trade growth forecasts. Signs of trade frontloading preceding this tariff shock are evident – particularly in tariff epicentre US (shown by a dramatic turnaround of net exports’ contribution to Q1 GDP), but also for China and the eurozone. Evidence for the Netherlands is limited so far. Following the escalation of the US-China trade war, fears of a new China supply shock hitting European markets have risen. However, besides risks, this also creates opportunities for European companies.

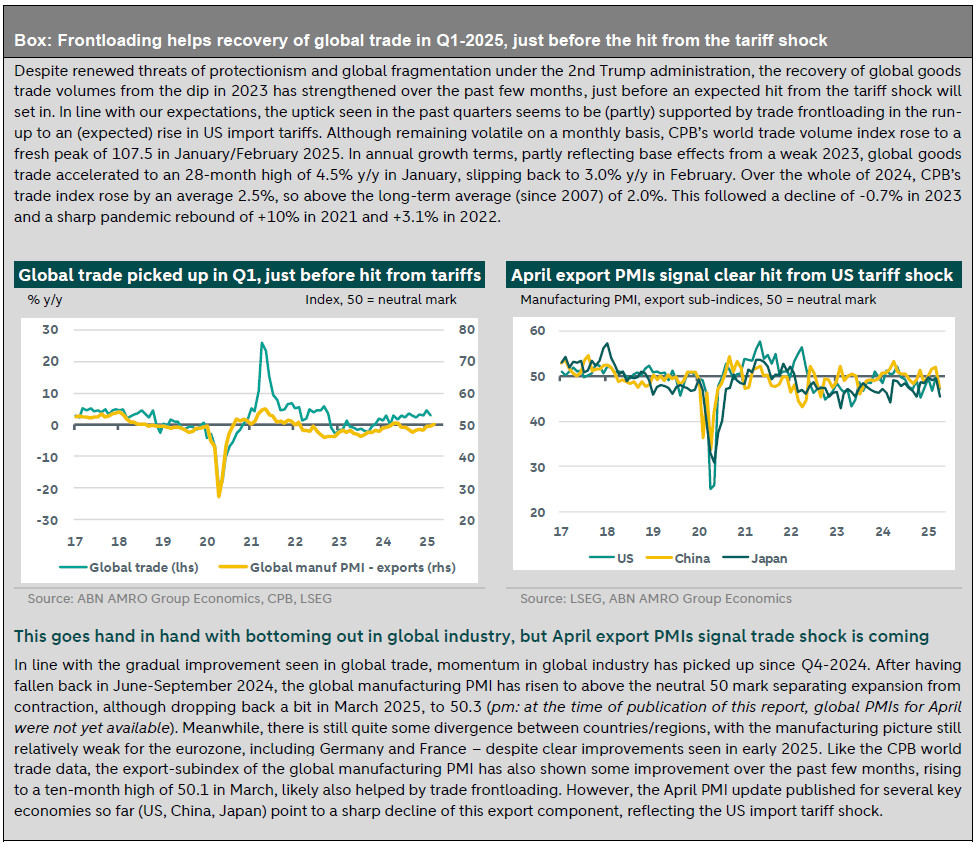

Calm before the storm? US import tariffs are expected to hit global growth and trade sharply

Despite renewed waves of protectionism and global fragmentation under the 2nd Trump administration, the recovery of global trade and industry has continued in end-2024 and early 2025 (see box for a cyclical update). This has been supported to some extent by trade frontloading, the main topic of this global trade update. That said, we think this recent robustness is a reflection of the calm before the storm, as US import tariffs are expected to hit global GDP and trade growth soon.

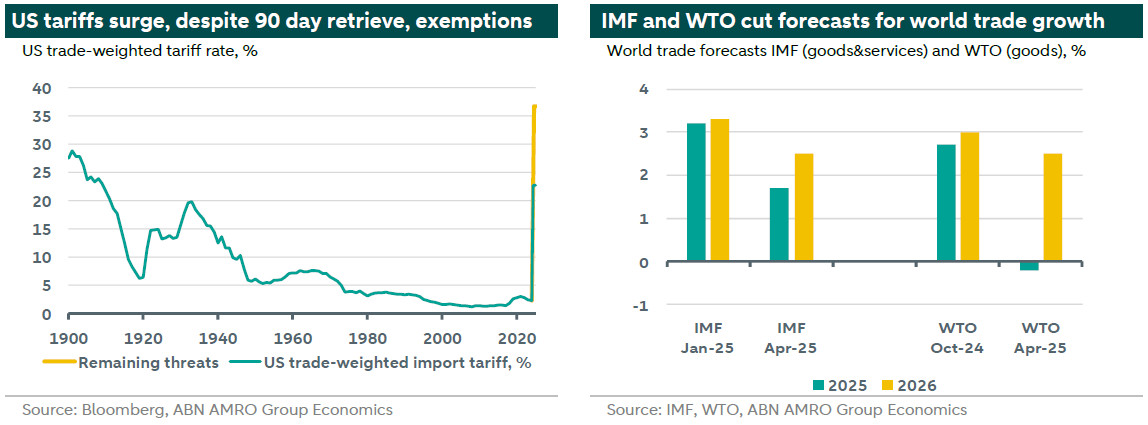

In fact, we have seen many developments on the US tariff policy front in April, with an initial sharp raising of import tariffs and a subsequent backtracking following an intensification of US market pressures and lobbying from US firms. Broad reciprocal tariffs were announced on 2 April, then un-announced (or at least paused) a week later, negotiations were started but without clear goals, and almost on a whim, the US focused its tariff ire squarely on China. This seemed to be Trump’s way of engineering a face-saving climbdown, with a 90 day pause announced for the biggest tariff rises on countries that have held back in retaliating against the US. Trump has since climbed down further, for instance exempting consumer electronics from the 145% tariffs on China imports, and later on for auto parts. More recently, the US’s tone versus China has softened remarkably, but Beijing is currently feeling it has the upper hand in the conflict and is playing ‘hard to get’ (see our April Global Monthly for more background).

Although the recent reversals reduce some of the tails risk to the global economy, the tariff package that remains in place is massive and there are still threats in the air, like product-specific tariffs on pharmaceuticals, semiconductors/ electronics, or even critical metals. Moreover, the full reciprocal tariff package may still come into play within a few months. What is more, the unusually large trade-policy related uncertainty remains which by itself hurts growth, and the tariffs will likely cause a large growth shock upon implementation. In fact, container transport bookings into and from the US already showed sharp declines in early April, with for instance Port of Los Angeles stating it expects a 35% drop in incoming cargo next week as shipments out of China destined for retailers and manufacturers have almost come to a halt due to the tariff escalation.

Strikingly, mainly due to the impact from US tariff policy and countermeasures, the just lowered its forecasts for world trade volume growth (goods and services) sharply, to 1.7% for 2025 and 2.5% for 2026 (from 3.2% and 3.3%, respectively). And the just cut its 2025 forecast for global merchandise trade volume (goods only) from +2.7% to -0.2% due to the escalation on the tariff front. The WTO also presented a more negative scenario, with the reactivation of suspended reciprocal tariffs by the US and the spread of trade policy uncertainty leading to a 1.5% contraction of global trade volumes this year.

Some theory: Frontloading typically precedes a tariff shock

Confronted with unprecedented tariff shocks that hit global supply chains and persistent (trade) policy uncertainty, companies are trying to mitigate and circumvent the impact of tariffs on their business models. A way to do this in the short-term is through a frontloading of trade. This is an important factor to take into account when tracking the business cycle, as it can cushion the blow of tariffs in the short-term. It could also create more volatility in the data, as there would be a stronger decline in trade following the frontloading period.

The basic idea of trade frontloading is simple: US companies increase their imports and stockpile before the tariffs come into effect. There may be various reasons underlying this approach, such as a) to prevent margin losses in the near term, b) to increase margins by selling the frontloaded goods after the tariffs raise domestic prices for a higher price, and c) to safeguard supply chain resilience by stockpiling critical inputs before they might become unavailable. Generally, the ability to frontload depends on the company, sector and the type of traded good.

In previous tariff episodes, it is well documented that frontloading is one way businesses respond to looming tariffs. For instance, retailers in the US increased their imports from China when the tariffs were announced in 2017. The concludes that the monthly tonnage that was imported from China increased by about 40%, which may have softened the blow to their profit margins at a later stage. For the Netherlands, the concludes that in the previous period when steel and aluminium were subject to tariffs, the total export value of these goods to the US rose substantially between the tariff announcement and implementation. Additionally, another concludes that: “the inventory buildup occurred despite increased consumer spending and strong economic growth”.

When determining the extent to which frontloading happens, uncertainty over future tariffs plays a large role. At the time of writing, there is a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs until July, for all countries except China, which is subject to a 145% tariff (but with exemptions for key categories such as consumer electronics, and car parts). Given the uncertainty, the extent to which frontloading happens also depends on whether companies believe the country-specific tariffs will be implemented still. This also holds for goods that currently hold an exemption, such as pharmaceutical goods. Since frontloading also comes with financing and storage costs, companies are attentive to these trade-offs.

Current evidence of trade frontloading

US: Imports surge in the tariff 'epicentre' is the clearest proof of trade frontloading

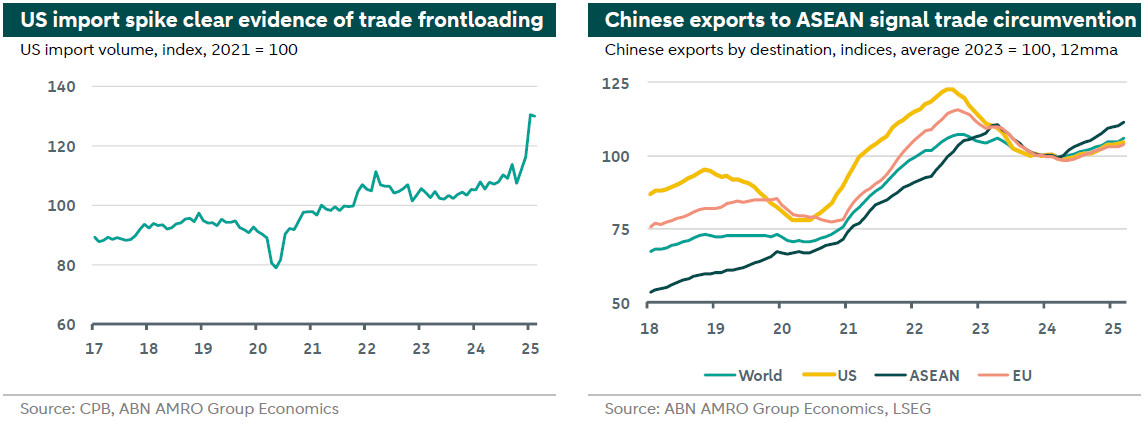

As trade frontloading mainly stems from the incentive to escape import tariffs (as explained above), it is quite obvious that the US – the ‘epicentre’ of the new wave of import tariff increases – should show the clearest indications of trade frontloading. A large chunk of total US imports are affected by tariffs (threats), while for most other countries only a limited part of total exports (i.e. mainly those heading to the US) is impacted. And indeed, CPB trade data show a surge of US import volumes over the past few months. The sharp rise in US imports is also visible in the dramatic turnaround in the growth contribution from net exports to US GDP in Q1-2025 (to a record drag of -4.8pp, from +0.3pp in Q4-24), with total USD GDP contracting by -0.3% q/q saar in Q1 (also see our update here).

China: Frontloading supported growth just before export hit: rising exports to ASEAN signal renewed trade circumvention

In China, various indicators are pointing to a frontloading of exports in late 2024 and early 2025 in the run-up to the (expected) rise in US import tariffs, which has supported GDP growth in the past two quarters. Export growth has generally picked up since Q4-24 (leaving aside a Lunar New Year related drop in February), and reached a five-month high of 12.4% y/y in March. Moreover, the export sub-indices of China’s two manufacturing PMIs have also risen in the course of Q1-2025, just before falling sharply again in April - as the April escalation of the US-China trade war became evident in the PMI data (see China – April PMIs show trade war hit).

Looking at the development of Chinese exports per destination, the strongest signs of trade frontloading are visible in exports to South East Asia (ASEAN), which rose sharply in late 2024 and March 2025. Exports to the US also picked up in late 2024, but hardly spectacularly in comparison to exports to ASEAN. This may be an indication that Chinese exporters have already started to prepare for trade circumvention routes in the run-up to the (expected) hike in US import tariffs versus China. Recall that this practice of circumvention via countries such as Vietnam was widely used after the first US-China tariff war in 2018-19. Incentives for such circumvention routes have become even stronger, now that China faces 145% overall import tariffs (except for categories such as consumer electronics or car parts) while South Asian nations only face a universal 10% tariff at the moment.

Eurozone: Pieces of the puzzle are there: Frontloading to provide some short term cushioning for struggling industry

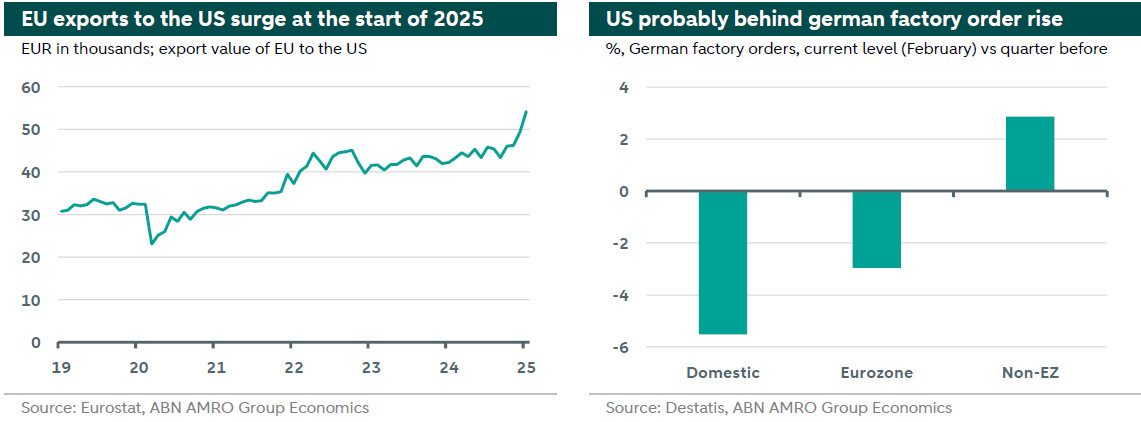

Since the start of the year we see a boost in eurozone exports to the US (in value terms) in aggregated trade statistics, rising by about 11% on a 3m/3m basis. Corroborating this data with more survey and disaggregated data (see below) also shows some frontloading of eurozone exports to the US taking place. While the scale, or the specific product categories being frontloaded, is hard to discern at this stage, we take the view that frontloading is providing a short term cushioning factor, especially for the eurozone’s struggling industry, rather than something that will massively move the macro needle. Indeed, the Q1 headline GDP release, while the breakdown of GDP lacks at this stage, dit not point to a massive contribution of frontloading to eurozone growth. Looking forward, we expect less frontloading, primarily as the scope to frontload has narrowed. The top three categories of goods that the eurozone exports to the US are pharmaceuticals (and broader medicaments), transport and vehicles, such as aircraft (parts) and car (parts), and other machinery. Of these categories cars are already subject to a 25% tariff rate. With threats on pharmaceuticals still being aired by the US administration, frontloading in that product category could well continue.

Next to the export data we see signs of frontloading in for instance the eurozone manufacturing PMI. In March, the output component of the Manufacturing PMI moved into expansionary territory for the first time in two years, while the overall manufacturing PMI remained in contractionary territory. The same trend can be observed in export-powerhouse Germany (22.7% of EU exports to the US), where both output and new orders subcomponents moved into expansionary territory. Frontloading was flagged in the S&P Manufacturing PMI press release as a factor mentioned by survey respondents for this rise. German factory order data showed this output increase was preceded by an increase in demand from non-EZ countries. Indeed, factory orders from outside the eurozone expanded in February (+3.4%) while orders from within the eurozone contracted. As a result Germany’s exports to the US, in value terms, increased by 8.5% in February. While export data is volatile on a monthly basis, together with rising demand and output the picture likely points to trade frontloading.

The Netherlands: Frontloading less clear in activity data, but businesses do report it

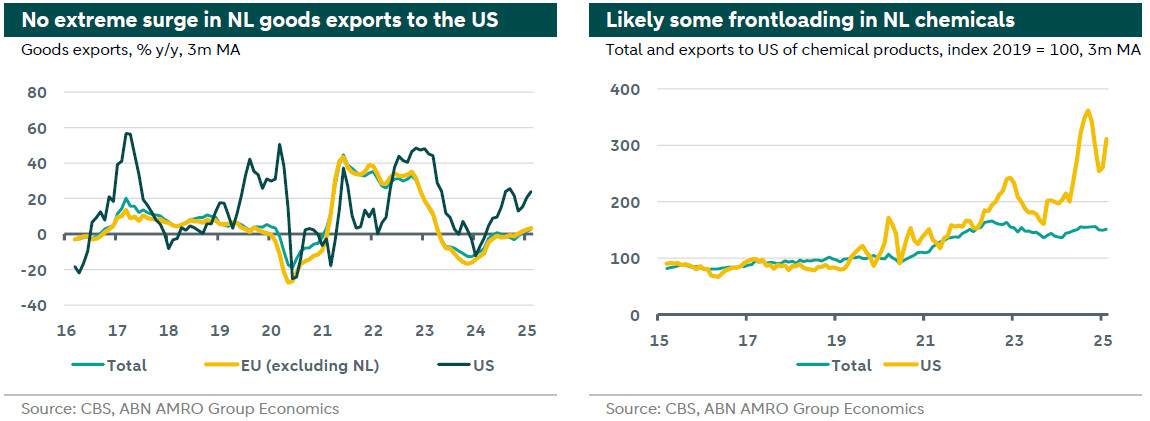

So far, the macroeconomic evidence of US frontloading from the Netherlands is limited. Goods exports to the US tends to be lumpy when compared to total exports and those to the EU. Although there is a small y/y uptick in exports to the US towards the end of 2024 and in the beginning of 2025, these figures are not extreme historical outliers. As Germany did display signals of frontloading, we anticipated a small effect from increased exports of Dutch suppliers to Germany. The trade subcomponents of the GDP release, however, show that this was not enough to sustain exports, as they decreased by 0.8% q/q in Q1 of 2025.

Chemical products, a significant export category to the US, do show signs of frontloading with exports surging near the end of 2024 and in the first two months of 2025 (see below right chart). Pharmaceutical products are currently still exempt from tariffs, which may incentivize continued frontloading. The exports of machinery and transport items also experienced a spike around the US elections and at the end of 2024, but likely due to the lumpiness of products within this category. Going forward, we expect to see some signs of frontloading for exempted goods further ahead. However, these signs of strength will likely be offset by reduced exports to the US in products already hit by tariffs.

A recent questionnaire conducted by the CBS reveals that companies indicate responsiveness to geopolitical changes. For example, over 25% of companies in the transportation industry report increasing their inventories to buffer against unexpected supply chain disruptions. Additionally, more than 30% of companies in the beverages industry and 22% in the metals industry are adjusting the countries from which goods are sourced or where output is distributed. These responses indicate that companies are reacting to signals of geopolitical uncertainty.

Will Europe be flooded with (cheap) products from China? There are risks, but also opportunities

Following the escalation of the tariff war between the US and China, the question pops up whether European (and other) markets will be faced with an abundance (cheap) Chinese products that cannot find their way to US markets directly anymore. Recent Chinese export data do not point to such a development yet, but this could change quickly. For Europe, this could potentially lead to even larger China supply shocks than the ones we have already seen over the past few years, with for instance the sharp stepping up of Chinese EV exports to Europe triggering an EU probe and the installation of EU tariffs on EV imports from China in 2024. EU policy makers are aware of these issues, are preparing potential measures and are in talks with Beijing about this.

While we are aware of the risks in this area, we also see some potentially mitigating factors and opportunities. First, the (temporary) exemption of consumer electronics from reciprocal tariffs will soften China’s direct export shock to the US. Second, trade circumvention (for instance through South East Asia, see above) could also mean that Chinese products still find their way to the US as a final destination. Third, China currently needs to carefully manage its relations with other key trade partners such as the EU. Hence, Brussels may be in a relatively strong position versus Beijing at the moment to negotiate beneficial trade and investment agreements, while at the same prevent Chinese ‘dumping’ on the European market. Related to this, US-China trade decoupling will also create opportunities for European firms, as the high bilateral tariffs will make European companies more competitive versus Chinese and US firms to serve the US and Chinese markets, respectively. We will continue to closely monitor and analyse developments in this area.