Macro Watch - A wage-price spiral is now much less likely

Wage growth, and the risk that it could keep inflation elevated, is now much less of a worry than early last year. In the eurozone, current wage growth is still elevated, but leading indicators point to a sharp decline this year, and businesses have been absorbing wage growth into their margins. We therefore see the risk of a wage-price spiral to now be very low. In the Netherlands we also expect an easing in wage pressures, albeit a more gradual one. In the US, wage growth was less of a worry to begin with; that remains so, but the recent spike in inflation expectations bears watching.

Wage growth is normalising, but rising inflation expectations bear watching

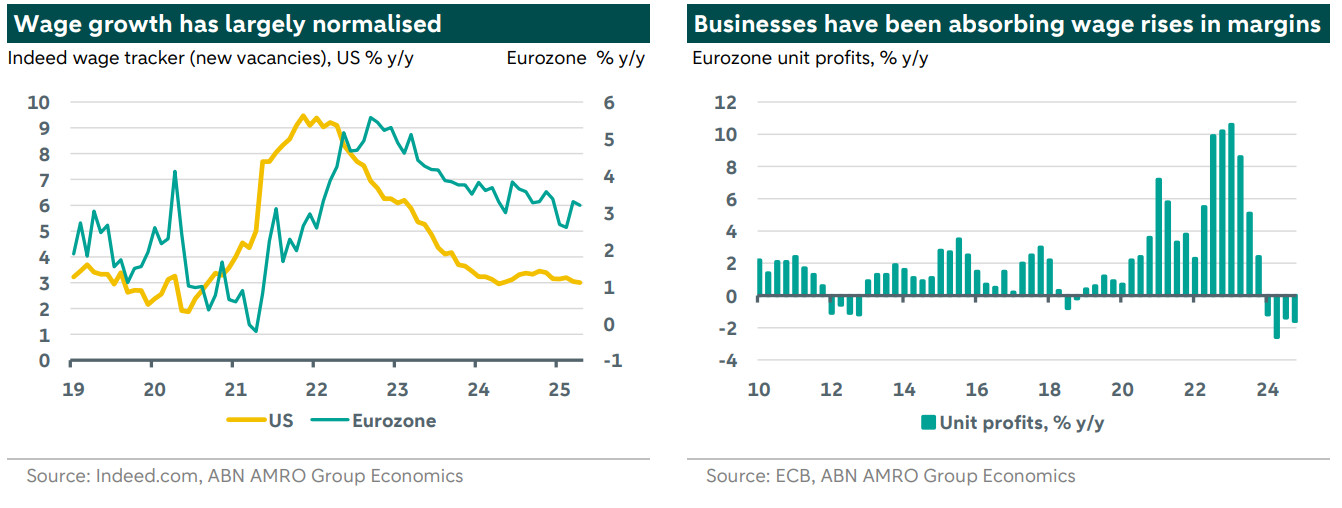

This time last year, elevated wage growth in Europe was the key concern ahead of the start of rate cuts (in the US, this was less of a worry). While many indicators pointed to a normalisation, ECB Governing Council members had to take a leap of faith and trust that wage growth would cool further, but also, that businesses would absorb a large part of the still-elevated wage growth in their margins rather than pass it on to consumers. The latter would have sparked fears of a wage-price spiral. What has happened since then? Amid a sea of worry in other macro-economic domains, wage growth is one area where things have evolved largely in line with expectations. Various measures of wage growth have shown signs of peaking, and leading measures – such as the Indeed tracker for new vacancies, and the ECB’s forward-looking tracker for negotiated wages – are already at or below levels consistent with 2% inflation over time (see our note last year for more on what we mean by this). Moreover, in line with ECB expectations, businesses have indeed absorbed much of the recent wage growth into their margins, and wages have now broadly caught up with prices following the energy crisis in 2022. Absent a new inflationary shock, then, a wage-price spiral now looks more like a remote possibility than an imminent risk. Even with a renewed spike in inflation, labour market tightness has eased significantly, lowering the chance of second-round wage demands, as worker bargaining power is not as strong as it was a couple of years ago. Low risk does not equal no risk. In the US especially, the recent tariff-induced surge in consumer inflation expectations bears closely watching. But in our base case, wage growth is not expected to be a source of inflationary pressure over the coming years.

Eurozone: Wage growth looking less likely to be a source of inflationary pressure

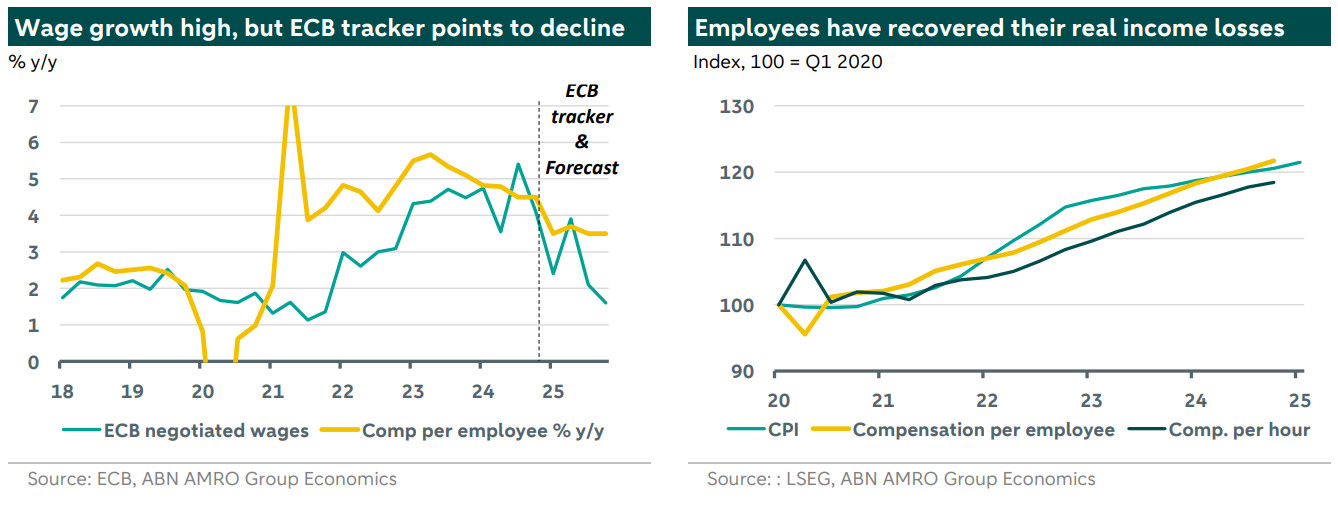

Since our publication on wage growth early last year, various measures suggest eurozone wage growth is peaking, while the forward-looking indicators point to a sharp decline by the end of this year. Specifically, the Indeed monthly tracker has moved from a 3-4% range to a 2.5%-3.5% range – in our view consistent with the ECB meeting its 2% inflation target over time. The ECB’s negotiated wages data also posted a sharp decline in Q1 25, to just 2.4% y/y from 4.1% in Q4 24, though this decline was flattered by a sharp fall in bonuses in Germany, influenced by tax changes. Underlying negotiated wage growth as well as compensation per employee (the most comprehensive measure of wages) remain on the high side at around 4% as of Q4 24. However, these are highly lagging indicators and for the most part reflect wage agreements made a year or more ago. The ECB’s forward-looking tracker for negotiated wages meanwhile points to a sharp fall to just 1.6% by Q4 2025, or 3% when excluding bonuses. The Q4 25 estimate is based on agreements representing 43% of employees across six major eurozone economies. While its coverage is naturally smaller the further out the projection horizon, the tracker has a fairly good track record in predicting realised wage growth. It is also consistent with the signal coming from the aforementioned Indeed tracker for new vacancies.

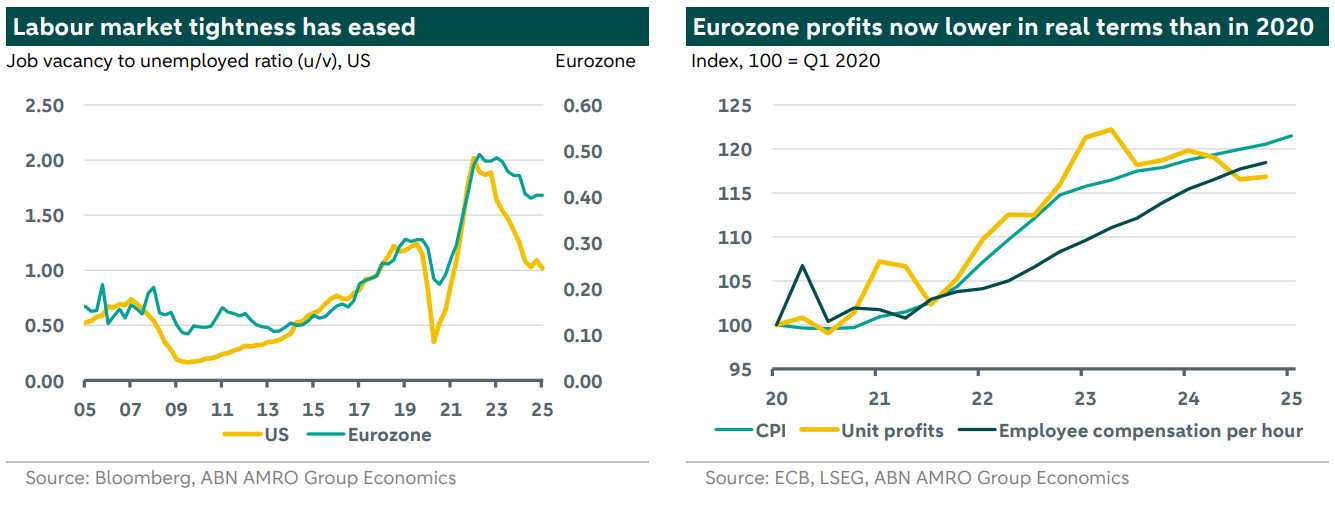

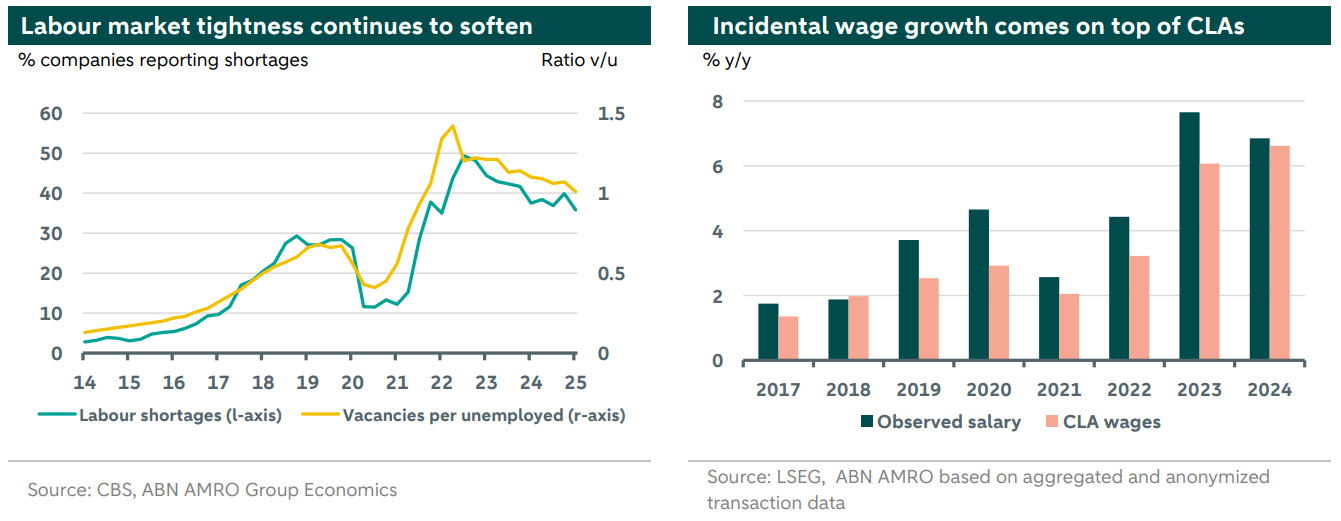

What has driven the moderation in wage growth? First, although compensation per hour continues to slightly lag the rise in prices since the pandemic, compensation per employee has now fully caught up. In other words, workers have seemingly opted to work longer hours to try to make up for the persistent (albeit modest) shortfall in compensation per hour. Given that the desire to compensate for the surge in inflation was the key driver behind the surge in wage growth, this has been a crucial factor capping wage demands. The second key factor is the cooling in the labour market. While the unemployment rate has defied expectations and continued to move lower, the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed people (a more useful indicator of labour supply-demand dynamics) has clearly peaked, and continues to move gradually lower. In other words, workers have less bargaining power than they did a couple of years ago. While the vacancy ratio remains historically high by eurozone standards, it is still low in absolute terms compared to countries with tighter labour markets such as the US, UK and some countries within the eurozone, such as the Netherlands.

Businesses have absorbed high wage growth into their margins amid weak demand

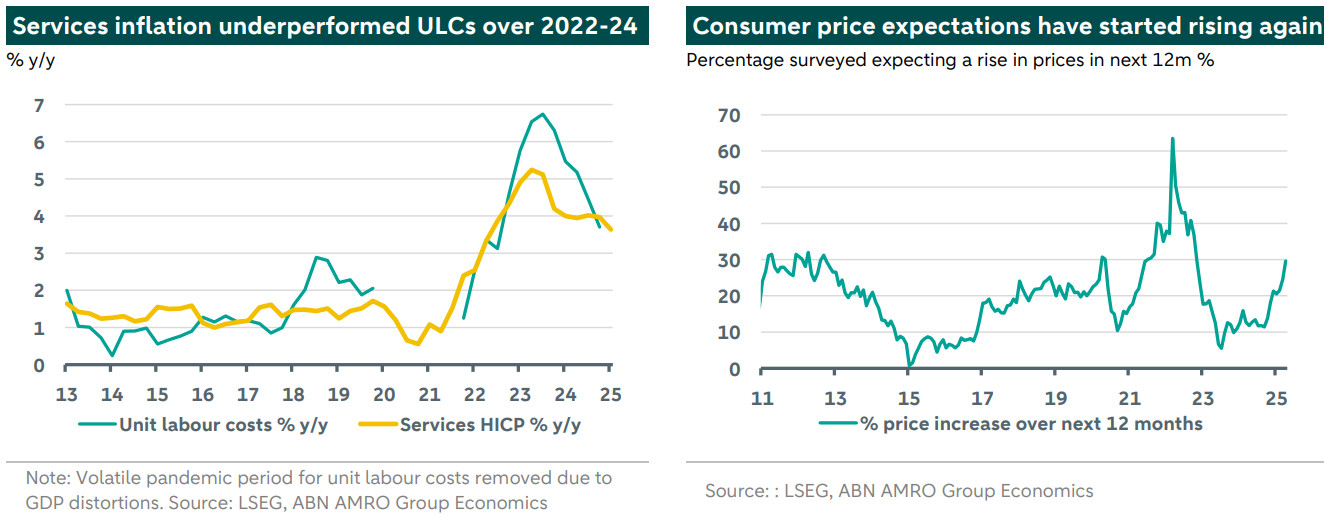

Even though the most comprehensive measures of wage growth are currently on the high side, businesses absorbed much of this into the profit margins in 2024. Following a period when businesses expanded profit margins – riding the high inflation wave of 2021-22 – the stagnation in consumer spending that resulted clearly hit producer pricing power. As such, growth in unit profits swung from an average 7% growth in 2022-23 to -2% in 2024. Indeed, in contrast to wage measures, which have continued to catch up with consumer prices, profits have actually fallen behind consumer prices and are now lower in real terms than in 2020 (see chart on previous page). This, it should be noted, is consistent with the expectations of ECB Governing Council members, who last year began cutting rates partly on the expectation that high wage growth would not only be temporary, but that it wouldn’t be passed on fully to consumers, risking a wage-price spiral. This is clearly visible when comparing services inflation with unit labour cost growth. While services inflation did accelerate and remains somewhat on the high side, it has generally underperformed (and the peak is much lower than) that of unit labour cost growth. With wage growth now on course to fall sharply over the coming months, we expect services inflation to continue to fall in tandem. This should still leave some room for business profit margins to start recovering again in the course of this year.

Looking ahead: Wage and services inflation to diminish further, but expectations bear watching

Overall, our conviction has strengthened that wage growth will not be a source of persistent inflationary pressure. Leading indicators clearly point to a sharp decline in wage growth over the coming months, and services inflation is expected to follow suit. With that said, there are still some reasons for vigilance. First, the labour market is still relatively tight compared to before the pandemic, and although we expect that tightness to ease – particularly given the looming hit to growth from US tariffs – the labour market is still likely more vulnerable to second-round effects from an inflation shock than it was before the pandemic. Second, although we have long thought US tariffs will have a strong disinflationary effect in the eurozone, consumers for now seem to think otherwise, with the European Commission’s survey showing a sharp rise in 12 month ahead expectations recently (see above; longer-run expectations remain well anchored). This is likely to dissipate once consumers realise that inflation is moving lower and not higher, but this dynamic bears watching over the coming months. Meanwhile, as we move into 2026 and higher eurozone defence and German infrastructure spending start to gain momentum, the risks to the inflation outlook are likely to start tilting upward. However, such inflation effects are typically lagging, and so this is more likely to be a 2027 story (if it materialises at all).

The Netherlands: Wage growth has peaked, but still elevated and contributes to long CPI tail

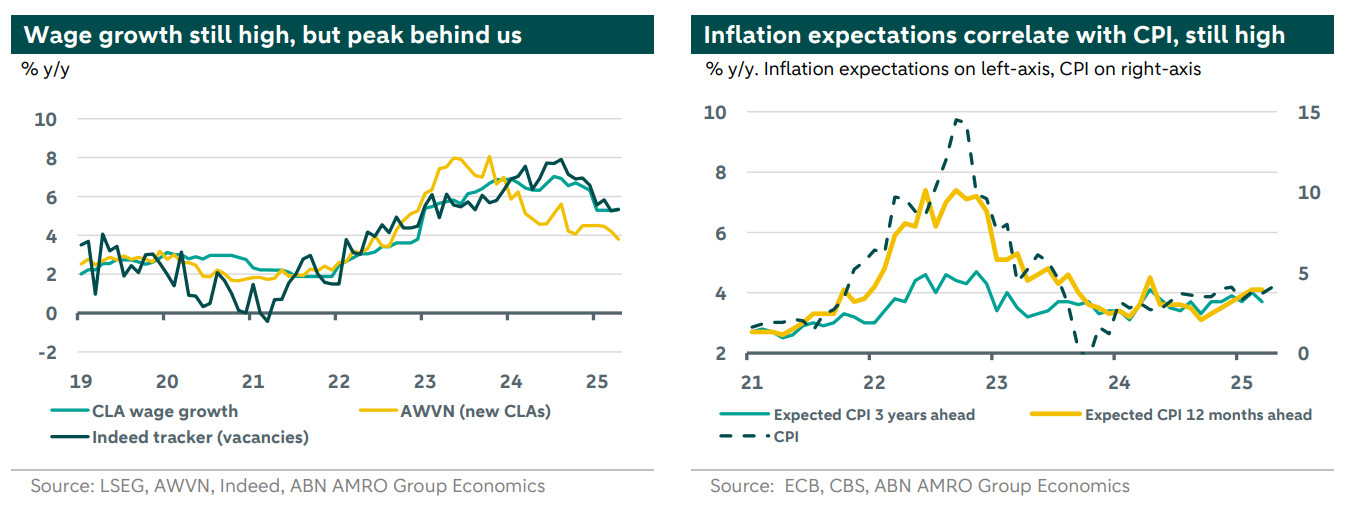

Due to the higher inflation peak in 2022, the Netherlands has experienced a more significant wage catch up, resulting in larger second round effects on services prices. From its peak at 7% y/y in July 2024, wage growth is gradually trending down. Indicators such as the AWVN measure of new CLA-growth and the Indeed tracker for new vacancies foreshadow a continuation of this downward trend. In April, the AWVN measure fell below the 4% threshold for the first time in two and a half years.

While wage growth is declining and the risk of a wage-price spiral is limited, the still elevated wage growth is a contributing factor to the long tail of inflation* . As a result, Dutch inflation is forecasted to continue to exceed the ECBs 2% target for the coming two years. In April, CLA-wage growth stood at 5.4% y/y, surpassing the inflation-neutral bandwidth of 2.2-2.8%, which we have based on both short- and long-run productivity estimates. There is likely some upside room to this bandwidth given the volatility in figures across various sectors. Similarly, companies can also absorb (some of) the wage growth rises within their profit margins, so wage growth does not have to immediately return to this range. In line with the observed elevated wage growth, compensation per employee remains elevated. Due to the large share of labour costs in total costs, services inflation is heavily influenced by wage developments. As wage growth gradually declines, it will exert less upward pressure on the still high inflation figure.

* Other factors that add to the long tail of Dutch inflation are, for instance, higher rent indexation, product specific tax changes, and expansive fiscal policy.

We forecast CLA-wage growth to decrease to an average of 5% in 2025 and 4% in 2026, down from the 6.6% peak in 2024. Wage growth is driven by future inflation expectations, labour market tightness, and the catch-up of nominal wages with the price level. Inflation expectations are still elevated and have been gradually on the rise again, correlating closely with the actual inflation figure. This suggests that workers will want to protect themselves from new purchasing power losses in the future, thereby adding to current wage growth pressures; although by much less than during the inflation peak. The tightness of the labour market, represented by the vacancy-to-unemployed ratio, continues to soften. Nonetheless, the labour market remains relatively tight, and companies consistently report labour shortages as their main obstacle. This means that worker bargaining power persists, albeit less than in the previous two years. Finally, wages have largely caught up with the price level. When considering wage growth beyond regular CLA growth, such as in sectors without a CLA or for incidental wage growth like promotions or job changes, wage growth has exceeded the official CLA statistic. The catch-up with prices means less upward pressure on wage demands. On balance, we judge that wage growth will continue to decline.

The US: Wages still no source of concern

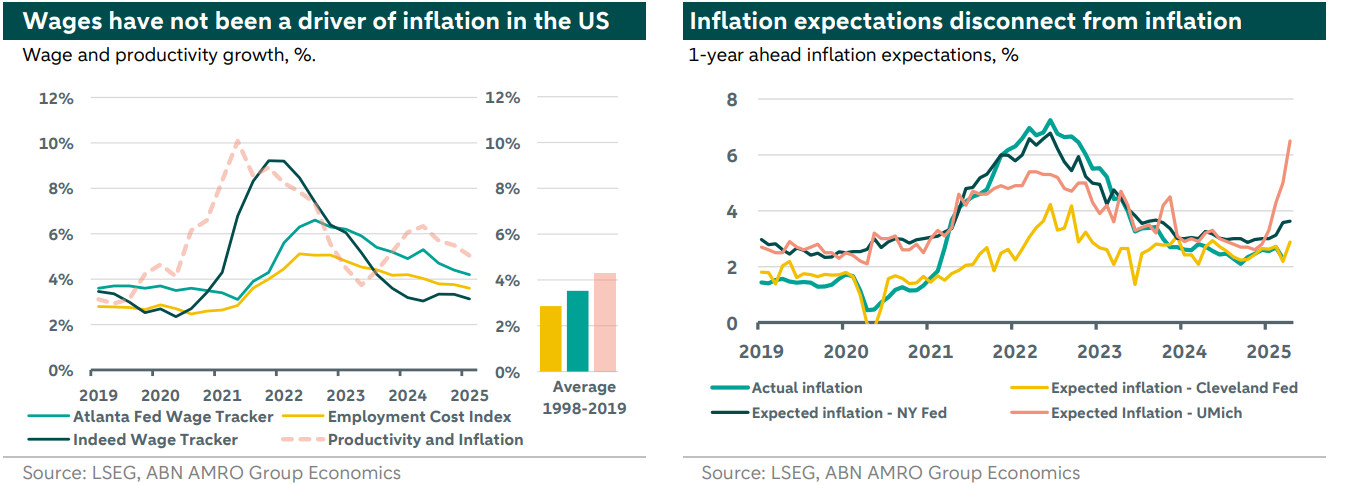

As described above, wage growth has been less of a concern in the US compared to the EZ. Data over the past year has not changed that view, with lower wage, but higher productivity growth in the US compared to the EZ. Wage growth remains well within the bound of the inflation + productivity benchmark, where wages provide little inflationary pressure. Compared to historical averages, wage growth is still marginally elevated regardless of the specific measure chosen, but this is counterbalanced by strong productivity growth over 2024.

In fact, there is still a significant gap in wage growth and price/productivity growth. Between 2020 and 2024, even Indeed wages only grew by 28%, while prices and productivity grew by 36%. By other measures, such as the Employment Cost Index (ECI), the gap is even wider. This is consistent with the declining labour share of income, which is relatively pronounced in the US. It suggests limited bargaining power, also limiting the probability of a wage-price spiral when inflationary shocks hit. Of course, US wages did respond to the recent inflationary episode. Initially, it was predominantly the bottom quintile of earners whose salaries rose substantially, helped by the overall tightness of the labour market, while more recently the higher earners have caught up.

Looking ahead, it is inflation, but more importantly inflation expectations that matter for future wage growth. Indeed, the latter is a better predictor of future wage growth than current or even future actual inflation. Driven by tariff worries, inflation expectations in the US have recently started to rise. This is most dramatically captured by the University of Michigan survey that suggests consumers expect inflation of 6.5% one year from now, but other measures from some of the regional Feds also are starting to show an increase. Usually these are highly correlated with current inflation, but now they show a clear divergence. While this increases the risk of wages becoming a source of inflationary pressure, we do not think these high expectations will ultimately be reflected in wage growth. With limited bargaining power of US workers, and with tariffs already putting pressure on margins of US firms, there will be limited room for wages to rise rapidly and become a source of, rather than a response to, inflation.

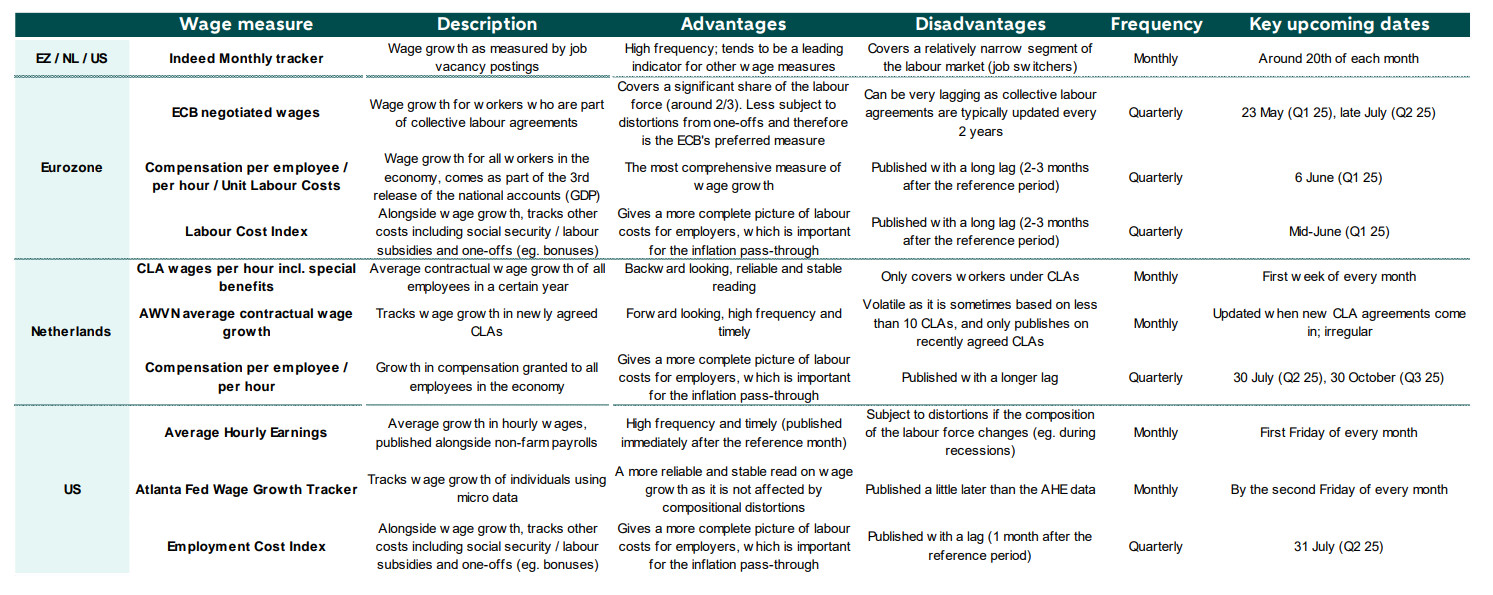

Appendix: Wage growth measures

Given the importance of wage growth for central banks, below we describe the most salient wage growth measures for each of the regions. We also discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each measure, the frequency at which they are published, as well as key upcoming dates at which data will be released. Upcoming releases will be crucial inputs for central banks in forming their outlook for inflation.