Sustainaweekly-There is still room for improvement in SBTi’s target validation methodologies

We have reviewed the different methodologies applied by the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) to validate targets. We also highlight three main pitfalls of the current approach: (i) the lack of a common baseline year, which makes comparison of different company targets challenging, (ii) the fact that no re-assessment of targets is required in case companies operate above their science-based decarbonization pathways, and (iii) targets estimated using methods that require assumptions on market share are also not re-calculated once new (and actual) information becomes available. Missing targets or a late baseline could prove disruptive to a company’s financial health, as also shown in the case of Dutch airport company Royal Schiphol Group.

We have extensively written about the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) (see for example, one of our previous notes here). The SBTi is a partnership initiative between Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). It was launched in 2015 (the same year of the Paris Agreement) and has as its main goal to validate whether a company’s targets are in line with what the latest climate science findings deem necessary to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement – limiting global warming to well-below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C. Below we have highlighted a brief overview of the methodology currently used by the SBTi in its process to validate targets, as well as potential shortfalls, where we see room for improvement.

The methodology used by the SBTi

The SBTi makes use of mainly three types of methodologies when validating alignment of targets to the Paris Agreement. All of them rely on so-called “carbon budgets” (or greenhouse gas budgets), which are amounts of carbon emissions that can be emitted over a period of time by a company before warming exceeds a specific temperature thresholds (such as 1.5°C). These carbon budgets need to then be allocated to the company, and this can be done through several different methodologies. Below we have included a brief explanation of three methods used by the SBTi.

The Sectoral Decarbonization Approach (SDA)

This method involves allocating carbon budgets based on the sector that the company operates in. The SDA uses the International Energy Agency (IEA) decarbonization pathways, comprising emissions and activity projections, to compute sectoral intensity pathways. The allocation is based on initial emission intensities (such as CO2/kWh) and companies’ market shares. The idea is that the sum of all individual companies’ emissions targets does not exceed the total carbon budget consistent with a decarbonization trajectory aligned with, for example, a 2°C mitigation scenario.

The IEA decarbonization pathways (and more specifically, the Energy Technology Perspectives) includes three emissions scenarios that run from 2014 and until 2060: the Reference Technology Scenario (RTS), the 2°C Scenario (2DS) and the Beyond 2°C Scenario (B2DS). It is mainly a bottom-up model, that relates energy supply to certain sectors. These sectors are, in principle, energy-intensive sectors, including for example power generation/utilities, iron and steel, cement, chemicals and petrochemicals, road transportation/aviation, etc. It therefore does not include all sectors (e.g. agriculture). A company operating in one of those sectors can rely on the IEA’s decarbonization path to estimate their total carbon budget.

In contrast to other methods (see more below), the SDA relies on a sector differentiation approach, and that can be particularly interesting as it therefore accounts for the fact that some sectors decarbonise faster or slower than the global average, and this is reflected therefore in a company’s carbon budgets. You can find the full methodology for the SDA method .

The Absolute Contraction Approach (ACA)

Contrary to the SDA, the ACA method relies on absolute emissions reductions in line with global decarbonization pathways. Necessarily applied for companies that operate in sectors that are not covered by the SDA, the ACA assumes a minimum equal percentage of emission reductions for every company. Under a 1.5°C scenario, for example, the ACA assumes an equal absolute reduction target for all companies of 4.2% per year. These are based on a series of scenario envelopes, which involves estimating temperature limit probabilities as per e.g. IPCC, emission budgets, year of peak of emissions, etc. The linear reduction rates are calculated based on the timespan 2020-2035, which aligns with the lifetime of a science-based target that is assessed by the SBTi and minimizes distortion. The full methodology can be found .

According to SBTi, this is the approach that the vast majority of companies setting science-based targets choose: two-thirds of the targets approved by the SBTi in 2020 used the ACA method to set targets limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

The Greenhouse gas emissions per unit of value added (GEVA)

The SBTi has recently moved away from this approach. Nevertheless, it is still currently applied in some cases, but exclusively to scope 3 (that is, indirect) emissions. Contrary to ACA, the GEVA method does not assume the same emission reduction for every company, but instead equates a carbon budget to total GDP and assigns a company’s share of emissions via its gross profit, since the sum of all companies’ gross profits worldwide equate to global GDP. Applicability of this method is currently restricted to modelling of scope 3 targets, as it may not constrain global emissions to a specified budget in its current formulation. Under the GEVA method, companies are required to reduce their GEVA by 7% per year (compounded). The 7% year-on-year reduction rate is based on an absolute emissions reduction of about 75% by 2050 from 2010 levels (baseline year).

What are potential shortfalls from these methods?

Using also as basis the paper by Rekker et al. (2022) named “Measuring corporate Paris Compliance using a strict science-based approach” (see full paper ), we have reviewed a few criticisms related to the three aforementioned methodologies.

Differences in baseline years

One of the biggest criticism related to the methodology currently applied by SBTi is the fact that the base year can vary depending on the approach being applied. For the SDA method, it is usually 2014 if following the IEA B2DS scenario. However, the ACA method (which is used by around 2/3 of the targets validated by SBTi) could allow for more recent years being used as baseline (e.g. 2020). As shown in the chart on the next page, there is currently a wide variety in terms of baselines being used by companies that have their targets validated by the SBTi.

The difference in terms of baseline year results in two main issues: firstly, different baselines result in lack of comparability amongst targets. This ultimately means that it is very hard (or nearly impossible) for investors to assess (i) the ambition of companies against their own peers and (ii) the extension of ambition aligned with the Paris Agreement (that is also due to the fact that companies make use of different methodologies – hence, hard for investors to judge which decarbonization pathway is more or less ambitious). On the latter point (and that brings us to the second main issue), Rekker et al. argue that the optimal baseline year should be 2015 or earlier. That is because this was the year in which the Paris Agreement was signed, and therefore captures emission reductions “well before 2020” – which is also a section of the Paris Agreement. Also IPCC makes use of the 2015 year as either base year or milestone in their analysis (see for example ), which makes the decarbonization pathway more aligned with its scenarios. A baseline year of 2015 ensures, as well, that companies are accountable for past emissions. As shown in the chart on the next page (right), only around 20% of the companies with validated targets have so far set a baseline year of 2015 or earlier. That ties well to the fact that 2/3 of the targets make use of the ACA method, which as we previously highlighted, allows for more recent target baseline years.

No “realignment” required in case company misses targets

Another pitfall from the current methodology applied by the SBTi is the fact that targets are not re-calculated in case they are missed. This is specifically important as carbon budgets are calculated based on e.g. a company’s market share. In the end, the absolute cumulative emissions until 2030 or 2050 for example determine whether the Paris goals of holding warming to less than 2 degrees are met, and that means that if a company fails one year, its projected carbon budget should also be re-adjusted and hence also its decarbonization pathway. Companies need to compensate by increasing their reductions in subsequent years and this means also decarbonizing at a faster pace.

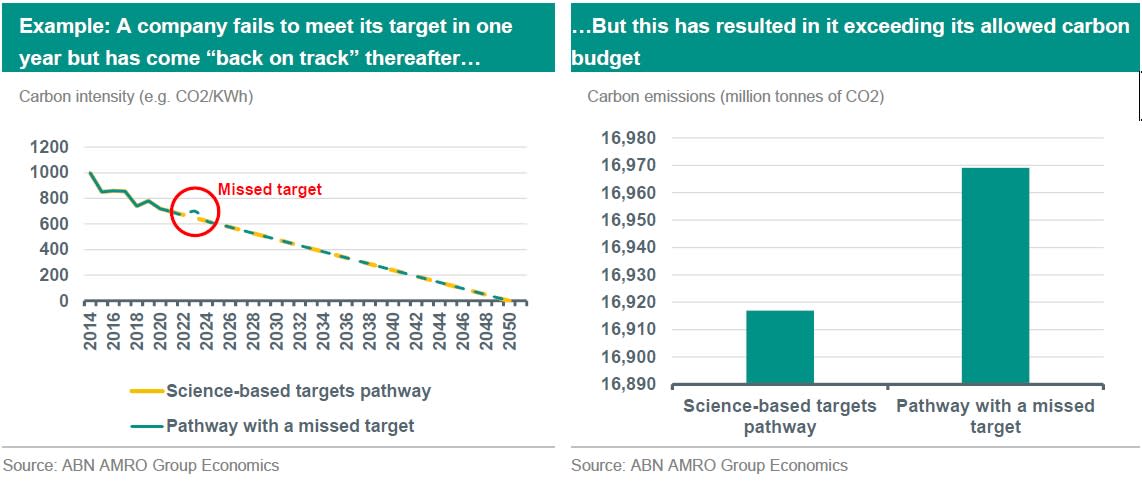

To make our point more clear, we would like to give a figurative example as shown below. Given that a company has only a limited carbon budget it can spend, if a company exceeds its budget within a certain year, it consequently needs to overcompensate in the years thereafter. So that means, more than exclusively looking at achieving a certain target within a certain year (e.g. carbon neutrality by 2050), this company needs to decarbonize at a faster pace thereafter in case it missed its targets within a certain year. The chart below on the right hand side shows a situation in which a company has within a certain year failed to meet its targets. Nevertheless, the following year, it has compensated and managed to be “back on track”. Ultimately, it has reached its initial carbon neutrality target by 2050. However, this resulted in it exceeding its carbon budget (see chart on the right hand side), which means that its initial decarbonization path was no longer compliant with the Paris Agreement.

Pathways re-calculated in case a target is missed necessarily rely on a faster decarbonization pace. The chart below on the left hand side (extracted from the paper of Rekker et al.) exemplifies how different pathways can take place depending on baseline year (blue line uses baseline year as 2020, while green line uses baseline year as 2014) and as well whether targets are missed or not (exemplified by the orange line). In both cases (missed targets and/or later baseline year) companies are required to speed up their decarbonization process in order to meet their carbon budgets, and this can be a highly disruptive process for the company, forcing them to accelerate the retirement of carbon-intensive assets and more rapidly mobilise capital to low-carbon assets. Hence, this faster transition can also have an impact on a company’s financial health, which is why it is so important for investors to not only focus on end goal targets (e.g. carbon neutrality by 2050) but to rather also do annual checks on whether companies decarbonize according to science-based decarbonization pathways.

A good example of how companies’ financials (and consequently credit quality) can be impacted by transition risks is the case of Royal Schiphol Group, the Dutch airport operator. A few weeks ago, the company was downgraded by both Moody’s and S&P on the back of the Dutch government’s decision to cap the number of flights due to environmental reasons. The company’s inability to act in due time to reduce emissions and control e.g. noise levels has resulted in government intervention, and this had a negative impact on the company. The need for now Schiphol to decarbonize at a faster pace will likely be cost intensive and disruptive, while the company will also suffer from the government restrictions in the near term.

According to SBTi latest data, around 12% of the companies have reported that they operated above their science-based decarbonization pathways. Given that pathways are not specifically disclosed (only end targets), this figure reflects the share of companies that reported a regress against emissions in their baseline year.

We acknowledge though that SBTi has been monitoring companies’ progress, and requires in theory the ones that missed targets to “explain why and the strategy for addressing these deficits in the future”. SBTi will also make it mandatory as of 2025 for companies to revaluate their targets every five years from the date of the original target approval. Nevertheless, immediate action is, at this point, not in the scope of SBTi’s work.

Pathways based on market shares are not adjusted regularly

Another important point to mention is that some of the methodologies applied by the SBTi (e.g. the SDA method) relies on assumptions about the company’s market share, and this ultimately determines its carbon budget. However, the SBTi does not require companies to recalculate emission pathways once the situation changes. That means, yearly checks on whether assumed market share (significantly) differs from actual market shares are at this point not taking place.

The SBTi does mention that “long-term targets, in particular, may require recalculation to update the company growth assumptions used to project the target and also to reflect the latest climate science.” However, as previously mentioned, at this point recalculating targets is more of a recommendation rather than a requirement. SBTi intends to make targets revision mandatory as of 2025.

This article is part of the Sustainaweekly of 10 October 2022