US - Fiscal cuts will add to the headwinds

The economy was resilient in April, even if downward revisions took off some of the sheen. Still, the economy is clearly not in a recession, despite the headwinds from high interest rates and inflation. Government spending cuts are expected to become an additional headwind going forward, as Republicans are unlikely to agree to a debt ceiling raise without them. The Fed is now in wait-and-see mode. Our base case continues to be for no further hikes, but strength in underlying inflation and labour costs will keep hikes on the table for the time being.

The US economy exhibited resilience in April, with activity data coming in broadly stronger than expected. This was, however, offset by downward revisions to older data – a common theme in the post-pandemic era. To illustrate: the 250k jobs gain in April was offset by a -150k net revision for the previous two months; the 0.5% m/m rise in industrial production was offset by a 0.4pp downward revision to March; and the 0.6% m/m rise in core nominal retail sales was partly offset by a 0.2pp downward revision to March data. Still, the economy is clearly not in a recession either, with private consumption growing at a robust 3.8% q/q annualised pace in the first quarter – largely on the back of an exceptionally strong January. Indeed, while the warning signs from credit conditions are clearly there, and global trade and manufacturing weakness are a drag, the US consumer is keeping the economy humming along for the time being (see this month’s Global View for more).

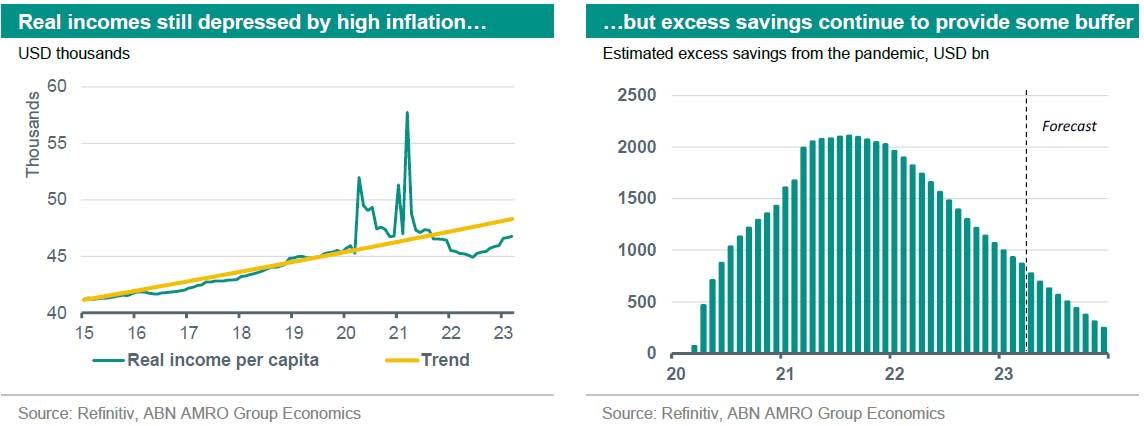

We continue to think this strength is unsustainable, given the headwinds from ultra-tight monetary policy and depressed real incomes due to high inflation, but timing the downturn is complicated, among other things, by policy lags and excess savings. Meanwhile, a further headwind still to come is from fiscal policy. While our base case is that a last minute bipartisan deal to raise the debt ceiling will be reached, this will not be costless to the Biden administration – nor to the US economy. Republicans will likely only acquiesce to something that involves substantial cuts to outlays. Relative to our baseline, this is likely to mean a reduced contribution from government spending to GDP growth and more job layoffs. In the meantime, there is a non-negligible risk that a deal isn’t reached in time, with signs that Republicans believe such a scenario may hurt Democrats more than it hurts themselves. This is contrary to the 2011 experience, but it goes without saying that failure to reach a deal in good time would mean a more severe recession than we forecast (see our Q&A for more).

Against this backdrop, the Fed has strongly signalled that it would pause rate hikes following its most recent 25bp hike in May, which took the target range of the fed funds rate to 5.00-5.25% (this level has some symbolic importance, as it was the ultimate peak in rates on the eve of the global financial crisis). The stubbornness in underlying inflationary pressure – and particularly the strength in unit labour cost growth – means that a tightening bias will likely stay with the Fed for the time being. But while the economy has proven more resilient than expected at this stage, rates are already highly restrictive (see Global View box), and given the lags of monetary policy it would appear prudent to monitor the impact of tighter credit conditions on the economy over the coming quarters. Should the economy prove more resilient than our forecast – which sees mildly contracting output in Q2-Q3 – the Fed could well be minded to raise rates somewhat further.

This article is part of the Global Monthly of May 23