US Outlook 2021 – Hey, big spender!

The US recession was more shallow than expected in 2020

Lighter lockdown restrictions, and an aggressive policy response have helped

The accelerating vaccine rollout points to a full reopening of the economy in Q2…

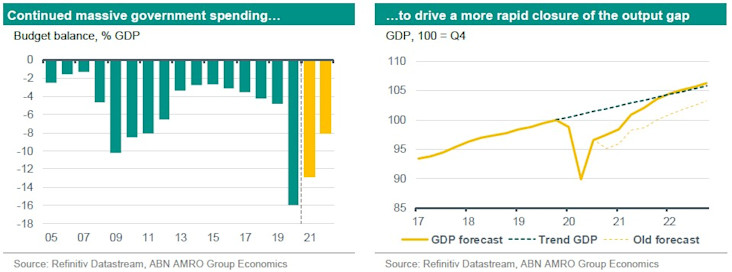

…while President Biden’s bold spending will drive a much quicker closure of the output gap

However, labour market frictions mean the fall in unemployment will be more gradual from here

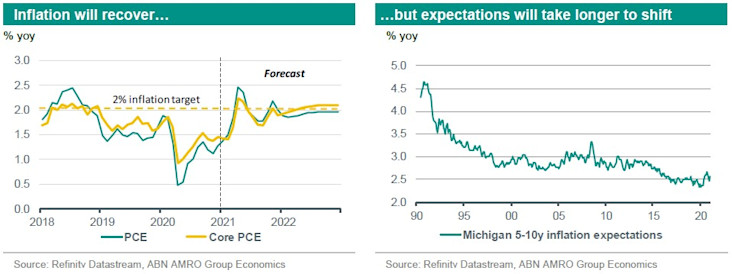

As a result, inflation should remain well behaved, and monetary policy will stay accommodative

A shallower recession and a stronger recovery

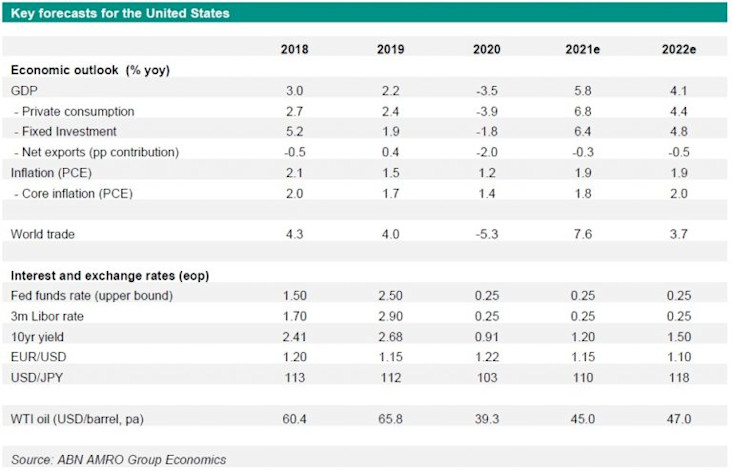

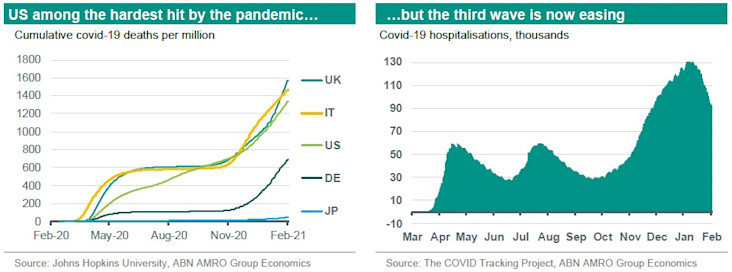

In its response to the covid-19 pandemic, the US has stood out from two angles: 1) from a public health standpoint, the US has been among the hardest hit; and 2) it is surprising therefore that the economic fallout has been comparatively shallow – the economy contracted by 3.5% in 2020, among the least in the developed world. We see three main reasons for this. First, the initial lockdowns in March and April were not as strict as those seen elsewhere. Second, fiscal and monetary support for the economy has been among the most bold and aggressive seen globally. Third, state governments have been much more reluctant to join European countries in imposing new lockdowns in response to the second and third waves of the pandemic in the latter half of 2020. Following a more shallow 2020 recession, the US also looks set to outperform in the vaccine-powered recovery of 2021. Newly-elected President Biden’s slim Senate majority, combined with prolonged easy monetary policy, gifts him significant power to spend aggressively to support the recovery over the coming years. As a result, we have significantly raised our growth forecasts, and expect a much more rapid closure of the output gap than we did previously.

Badly hit by the pandemic…

To understand where the US economy is headed this year, it is important to first understand why the economy has been much less hard hit than others. Although its third wave in the pandemic is now easing, the spread of new, more transmissible covid-19 variants could potentially mean it will enter a fourth wave over the coming months (notwithstanding the vaccine rollout, which is discussed later). By almost any public health metric, the US has been among the hardest hit among developed economies by the pandemic – it has among the highest cumulative cases, hospital admissions, and deaths per capita. Despite this, the lockdown restrictions have been comparatively mild. To some extent, this can be explained by politics: Republican-run states have been much less willing to impose lockdowns than those run by Democrats. However, it also appears that – barring some notable exceptions such as California – the second and third waves have not burdened healthcare systems quite as severely as the first wave. Indeed, while aggregate hospitalisations have been higher in the US, the geographical spread has been more even; no single state has seen hospitals strained as much as those in New York were in the first wave of the pandemic.

…but much milder lockdown restrictions

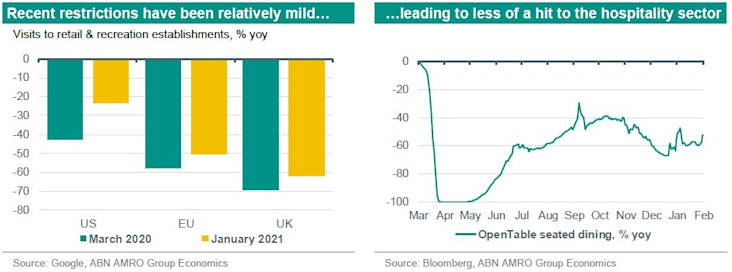

More limited lockdown restrictions has meant a much smaller decline in activity. This is confirmed by the Google Mobility data, which shows around a 20% yoy decline in visits to retail & recreation establishments in January, compared to more than 50% declines in most European countries. The OpenTable seated dining data shows that although hospitality has indeed taken a renewed hit, that hit is nonetheless much smaller than during the first round of lockdowns; restaurant dining is running at around half of normal capacity, whereas restaurants were completely closed in the first wave of the pandemic.

Aggressive fiscal support has also supported consumption

In addition to much milder lockdown restrictions, consumers have also surprised in their ability to substitute away from spending on restaurants and bars to higher physical goods consumption. This has likely been spurred by aggressive fiscal support, including two rounds of stimulus checks totalling $1800 per person (distributed to all but the highest earners), as well as generous top-ups to unemployment benefits that meant up to 40% of workers had been financially better off than when they were employed.

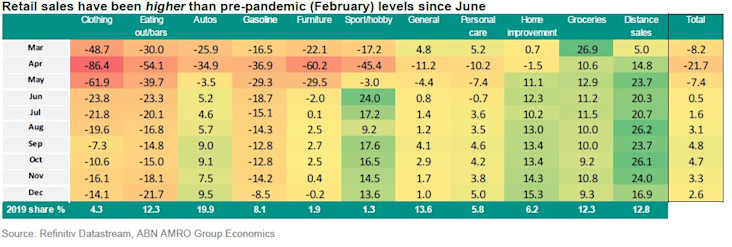

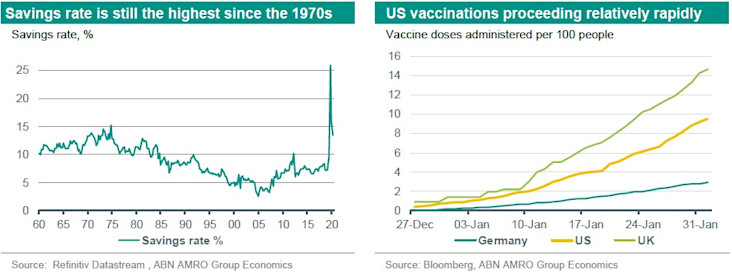

This substitution has mostly taken the form of higher online merchant sales, which have been 20-25% higher than the pre-pandemic period, as well as car sales (+5-10%) and home improvement (+10-15%). We previously thought extra consumption in these categories would be difficult to sustain, but there has so far been little sign of a major slowdown. The boom in these categories has been more than enough to offset weakness in the hospitality and clothing sales, and as a result, total retail sales have been consistently higher than pre-pandemic levels since June. Although surveys suggest consumers generally prefer to spend their stimulus checks on debt repayments or savings – and this is corroborated by the jump in the savings rate during the pandemic period – it appears that fiscal support has been so aggressive that it has nonetheless still had a stimulatory effect on consumption. These substitution effects have helped significantly in tiding the economy over through this period.

Outlook for consumption depends on the virus, but there are reasons for optimism

Looking ahead, consumption will remain supported by a fall in the elevated savings rate – which, at 13.7% in Q4, is the highest level since the mid-1970s – as well as further massive fiscal support in the form of a new $1.9trn (10% of GDP) package currently being debated in Congress. The latter proposes to extend generous top-ups to unemployment benefits, distribute yet another round of stimulus checks, as well as support for healthcare and state & local governments. We expect this to add 1.9pp to growth in 2021, and 0.6pp in 2022. With that said, further consumption gains will depend significantly on the scale of further reopening, which naturally will depend on the pace of vaccinations and the course of the virus itself. With regards vaccines, the US has been inoculating citizens at a relatively rapid pace of almost 1.5 million doses per day, enough for around 0.5% of the population. This is lower than the pace seen in the UK (which is inoculating 0.6% per day), and much lower than Israel (1.9% per day), but is likely to continue accelerating in the coming weeks as supply constraints ease. Considering up to 1/5 of Americans may already have acquired natural immunity, it is likely that enough of the population will have been vaccinated to provide sufficient relief to hospitals by the time the more transmissible new variants come to dominate – something epidemiologists expect to happen in March.

Among the few states with significant restrictions (such as restaurant closures), the largest – California and New York – already began reopening in January. This should support a recovery in the hospitality sector in Q1. A full reopening is likely in Q2, during which we expect consumption to fully recover back to its pre-pandemic level.

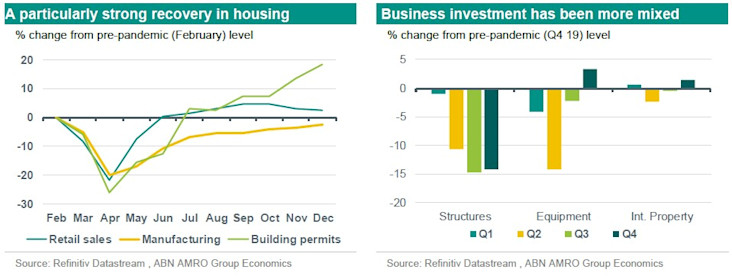

Housing investment is also rapidly rebounding

Alongside consumption, other parts of the economy have recovered at a similarly rapid pace. Housing investment has recovered particularly strongly, with housing starts the highest in 14 years. While some of this strength reflects pent-up demand from the lockdown period, it is encouraging that building permit approvals, a strong leading indicator for housing investment, have continued to surge, and are now at their highest level since 2004. Combined with the strong housing market – with prices rising 9.5% yoy as of November – this bodes well for housing investment over the coming quarters.

Bold investment plans to lift manufacturing and investment

Manufacturing – and in turn business fixed investment – have also recovered significantly, although there remain spots of weakness. Manufacturing has remained stubbornly shy of pre-pandemic levels, with the significant destocking of Q2 yet to be made up for. Given the sharp rebound in exports, we expect the recovery in manufacturing to accelerate this year. A further boost for the sector over the coming years will come domestically from President Biden’s $2trn (over four years) renewable energy investment plan, alongside a somewhat less ambitious $1.3trn (over 10 years) infrastructure investment plan. The details remain vague on these plans, given that they were election pledges, but a more detailed proposal is expected to be announced this month. Given the Democrats’ slim majority in the Senate, we expect these plans to be passed using the budget reconciliation procedure, with legislation likely to come in the second half of this year. As such, investment is likely to begin in earnest in 2022, adding c.1.5-2pp to growth. Combined with the $1.9trn pandemic relief package currently under discussion, we expect this spending to drive a much more rapid closure of the output gap – we now expect this gap to close by early next year, whereas we previously expected a persistent output gap on our forecast horizon.

Fiscal boost to drive further falls in unemployment, albeit more gradually than thus far

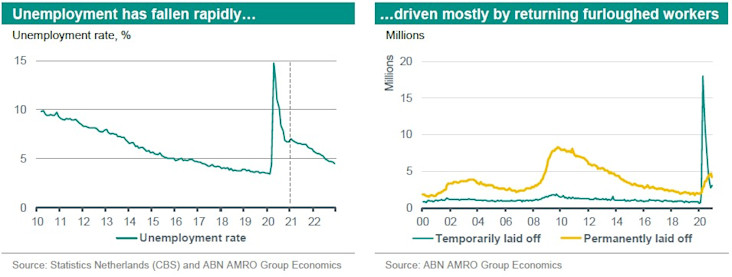

The unemployment rate has swung wildly over the past year, largely due to differences in how the US government provides support to furloughed workers. Unlike in Europe, where wages have been subsidised, workers in the US have been temporarily laid off and have received unemployment benefits to replace their lost incomes. As a result, the initial surge in unemployment gave the mistaken impression that jobs had been permanently lost. In fact, the bulk of job losses were temporary, and most of these furloughed workers have now returned to their previous jobs. With that said, there has been some significant permanent damage done to the labour market; at the peak, the rise in permanent layoffs compared to pre-pandemic levels reached almost 3 million. This number has since come down, albeit it a much slower pace than for those who were temporarily laid off. Some of the changes brought about by the pandemic – such as increased home working and reduced business travel – are likely to prove structural in nature. Workers that are dependent on such pre-pandemic patterns of demand – for instance, those in the hospitality sector in business districts – are likely to be more vulnerable to being permanently laid off. This more frictional unemployment will take longer to fall, with retraining and reskilling likely necessary. With that said, jobs growth will be helped significantly by the aforementioned avalanche of fiscal spending over the coming years, and we expect the US economy to be back at full employment (c.3.5-4%) by 2023.

Inflation should remain well behaved, allowing the Fed to keep rates low

The one big potential spoiler to President Biden’s ambitious spending plans is arguably inflation. Large deficits and a rising debt ratio can only be justified while interest rates remain low. While the Fed’s new policy framework gives it more leeway to keep rates lower for longer, a significant and sustained rise in inflation would be hard to tolerate for very long. Although inflation is expected to pick up this year, we do not expect it to be sustained. Base effects and higher oil prices will push inflation higher in the first half of the year, with the CPI measure peaking at around 3% yoy in April/May (PCE inflation – the Fed’s target – will peak at around 2.5%), before rapidly falling back as these base effects fall out. Later in the year, we expect a more meaningful recovery in core inflation, driven by a catch-up growth in housing rents, which were largely frozen during the pandemic. This will likely be enough to convince the Fed to taper asset purchases by next year. However, in order for higher inflation to be sustained, we would need to see this accompanied by a rise in long-run inflation expectations. History has shown us that inflation expectations tend to move only very slowly. As such, we are unlikely to see a significant and sustained rise in inflation expectations in the near term. However, with the output gap closing in early 2022, and large-scale fiscal stimulus potentially stoking some demand side pressures, it is possible that we see this further out – perhaps in 2023. This would not be soon enough to derail President Biden’s public investment agenda, but it could well mean we see a rate hike from the Fed by late 2023. However, with the neutral rate likely to have fallen even further since the pandemic, and the Fed’s stated desire to see higher average inflation over the business cycle, we expect any rate hikes to be much more gradual and limited than we saw in the previous cycle.