US services inflation accelerates

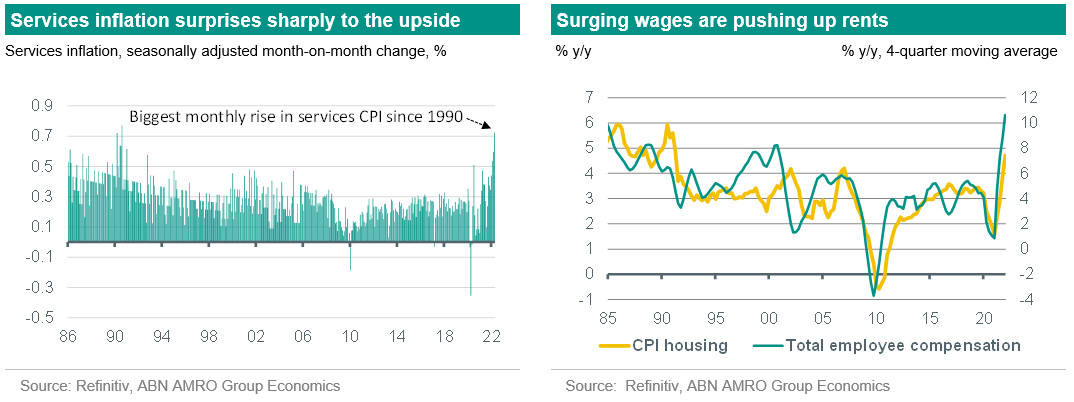

US headline inflation cooled in April, falling to 0.3% m/m sa from 1.2% in March, taking annual inflation down to 8.3% y/y from 8.5%. However, this cooling in the headline masked worrying underlying trends: services inflation accelerated sharply, rising 0.7% m/m – the biggest monthly rise since August 1990.

This comfortably offset declines in used car and clothing prices to keep core inflation unexpectedly high, at 0.5% m/m (6.1% y/y). While a significant driver of the upside surprise came from airfares – a knock-on effect from the run-up in oil prices – housing rents, medical and other services costs also continued to rise sharply, at around double the pace that we typically see in these categories. We view this as a spillover from on-going elevated wage growth, which although cooling a touch in recent months, remains elevated, with hourly earnings continuing to rise at around a 5% annualised pace.

Upside services surprise bodes ill for the outlook...

The report suggests the prospects are looking bleak for inflation to fall back to the Fed’s 2% target anytime soon, given that services inflation tends to be much stickier than other components, and given the risk that it drives a move higher in inflation expectations (according to the University of Michigan consumer survey-based measure, expectations remain reasonably anchored for the time being).

...keeping pressure on the Fed to hike in 50bp steps

The report all-but seals a 50bp hike taking place at the June and July FOMC meetings, and raises the risk that the Fed continues hiking at this pace in subsequent meetings. Following the report, we have significantly raised our inflation projections for the US, with headline inflation now expected to average 8% in 2022 and 4.1% in 2023 (previous forecasts: 6.9% in 2022 and 3.3% in 2023). Alongside firming services inflation, energy and goods inflation – a major drag in the April report – are set to rebound significantly in the coming months. Aside from higher oil prices, a shortage in refining capacity is raising the margin between crude oil and gasoline and jet fuel prices. Meanwhile, higher natural gas prices – something the US had been relatively immune from until recently – will also drive a rise in household energy bills.

A key question mark over the outlook remains the extent to which the hit to real incomes will drive a decline in demand, and the timing of this. While we have seen some decline in goods consumption of late, it is still not nearly to the extent that is likely necessary to bring demand back into balance with disrupted supply in the economy. The run-up in services inflation also suggests we will need to see a significant easing in labour market tightness to bring wage growth back down to more normal levels. The excess savings from the pandemic are providing some buffer to the real income hit for the time being, but this will not last forever, certainly for lower income groups. Something will therefore have to give over the coming months – and if it doesn’t, the Fed will have to tap even harder on the brakes further down the line.