US - This is what stagflation looks like

The Fed did a ‘risk management cut’ of 25 bps as inflation and employment risks approach balance. Tariffs and the immigration crackdown led to an immediate stagflationary impulse, but the overall picture is nothing like the 1970s yet. Early Q3 data is actually showing some signs of a modest recovery in consumption and investment.

The Federal Reserve lowered its policy rate by 25 bps to the 4.00-4.25% range. Markets had fully priced in the cut, and many more this year. There was near unanimity amongst the voting members, with only recent Trump-appointee Stephen Miran dissenting in favour of a 50 bps cut. In the press conference, Chair Powell framed the decision as one of risk management. Deteriorating labour market conditions, as evident in the unemployment rate ticking up, particularly for more vulnerable groups in the country, show that some of the downside risk to employment has materialized. The Committee now assesses the downside risks to unemployment and upside risks to inflation – which are still substantial as well – as more balanced, requiring the Fed to move the policy rate closer to neutral. Powell made it clear that this is by no means the worst economy he’s seen, but it is one of the hardest to set policy for. This was also clear from the unprecedented spread in the dot plot for the remainder of this year, which showed the highest dispersion of any September dot plot since its inception. The one-year ahead dispersion is in contrast relatively mild by historical standards, easily surpassed by the dispersion in 2014-2017, around the time of the zero lower bound and lift-off.

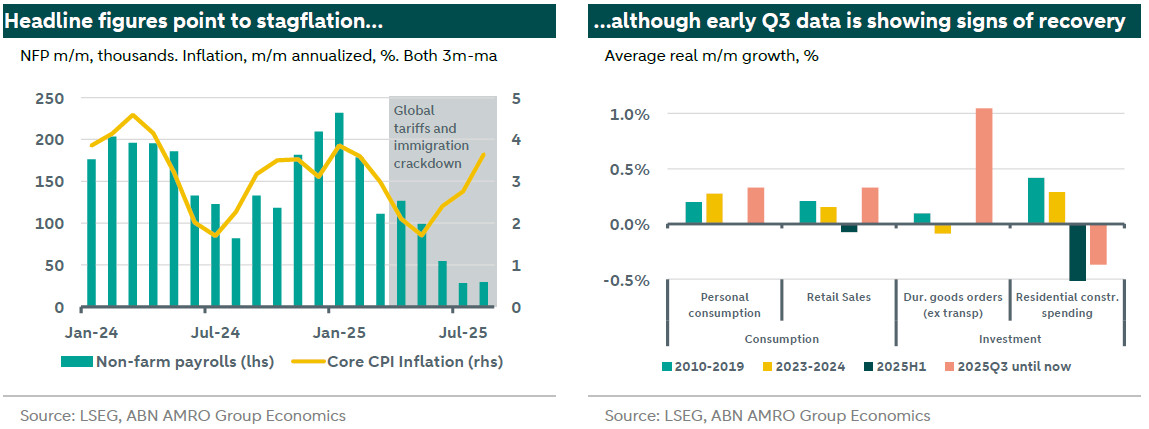

The chart on the left below exemplifies this near-term difficulty. Economic activity drove job gains and CPI inflation to largely track each other over 2024 and the start of 2025. Policy from the Trump administration has broken that connection and is moving them in opposite directions. Both tariffs and immigration policy are to blame. As for tariffs, we see goods inflation starting to pick up, but pass-through is still limited. Since consumers are hardly paying them, and exporters are not cutting prices, it has to be the companies in between dealing with the tariffs. They indicate they are keen to pass on the tariffs to consumers, but have been hesitant to do so. Partly this is due to a lack of urgency through inventory build-up, and partly this is due to prior uncertainty about tariff policy, and whether or not tariffs would stick. That same uncertain outlook also contributed to reduced hiring, further exacerbated by immigration policy. Labour force growth, a large driver of economic activity and job growth, has all but stalled. Lower supply by itself further dampens demand. Targeted deportation of undocumented workers hits particular industries especially hard, such as construction and importantly agriculture. Here we potentially also see an effect on inflation, with elevated food inflation readings, and anecdotal evidence of struggling farmers.

We haven’t seen the real impact of tariffs yet. The data until now largely reflects the effects of policy uncertainty. We expect inflation to pick up and to continue its recent upward trend, but the labour market to stabilize. Part of the reason for that is that we see some early signs of activity picking up again. The chart on the right above shows that after a weak first half of the year, early data on (goods) consumption points to a recovery. Personal consumption (which includes services and is adjusted for inflation) is only available to July, but retail sales comprises both July and August. Some proxies for investment, such as durable goods orders, also show a pickup on the non-residential side, but residential investment still appears in a slump. The latest trade balance figure was largely in line with pre-tariff figures, but we still expect net exports to reflect the unwinding of frontloading. On the back of these early data, and in line with our view that we’ll see some normalization now that most of the policy uncertainty has abated, we’ve upgraded our growth forecast for the upcoming quarters. The economy is still on course to grow by 1.8% this year, and that is without significant labour force growth. We therefore continue to see the upside risks to inflation outweighing the downside risks to the labour market, and expect upcoming data – and resulting Fed policy for the remainder of the year – to reflect that. We continue to expect the next rate cut to come in the first projection meeting of 2026.