Waiting on social impact

Social impact plays a big role in the public relations of companies. And the general public is increasingly interested. But what exactly is social impact? Will the EU taxonomy provide clarity? And is the market for social bonds as big as the hype suggests?

ABN AMRO Group Economics

Author has left ABN AMRO, see text

Author: Piet Rietman

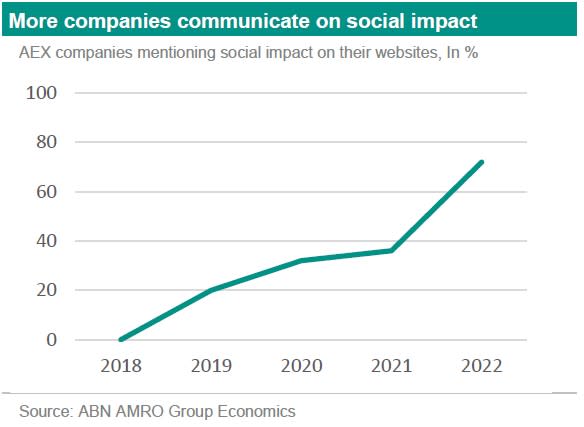

Social impact is becoming more and more important for companies. At least, when one looks at their communication. For instance, of the companies that are listed on the Dutch benchmark stock index, the AEX, 72% now mention social impact in some way on their websites. This was 0% five years ago. Half of the companies mentioning social impact focus do so by focusing communication on how social impact is provided for others, such as banks providing the possibility to invest in social impact.

All that communication creates some suspicion: do companies use social impact strategically, as a way to improve their image? Or are they truly making a social impact? Most academic research shows that both perspectives are true. For example, various academic studies (for instance by Wichaisri & Sopadang - see and Ait Sidhoum & Serra see ) show that companies choose which UN SDGs they want to address based on increased competitive advantage or in other words, self-interest. However, other studies (for instance, by ElAlfy & Weber see ) show that companies choose social impact goals based on what is actually relevant to their business. Choosing goals that companies can influence is an indicator that they are actually able to reach those goals.

To put it simply: companies actually want to make a social impact but also think they benefit from communicating about that.

The general public is increasingly interested in social impact

And there is a market for that communication. News websites and Google searches show an increase in interest in social impact around the time that the first draft of the proposal for a development of a social EU Taxonomy was released. But apart from this uptick in January/February, the general trend is also upward. The same goes for trends on social media, although they are also heavily influenced by companies themselves communicating about social impact.

The problem with buzzword or search term research however, is that is can reflect a multitude of different causes. For example, it could mirror a media trend. If journalists write about a subject that is considered vague, that drives media consumers to do their own research. In this case it wouldn’t necessarily mean that the general public is interested in buying from or investing in companies that claim to make a social impact.

But what exactly is social impact?

Vagueness is exactly the issue that surrounds social impact. Most definitions of social impact are very broad and are somewhere along the lines of “the positive effect that an intervention has on people or communities”. A lot of definitions have the word “positive” in them, such as “positive effect” and “positive intervention”, which is of course highly subjective.

A good example of the subjectivity involved would be Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February. German defence industry lobby group BDSV then stated that “The invasion of Ukraine shows how important it is to have a strong national defence.” BDSV appealed “to the EU to recognize the defence industry as a positive contribution to ‘social sustainability’ under the EU taxonomy.” While some would argue that weapons are never a positive intervention, the EU indeed in a policy paper the same month links the defence industry’s access to finance and investment to “horizontal policies on sustainable finance”. This proposal never was, however, never turned into policy.

And a good example of the broadness could be found by looking at government activity or government bonds. Government activity is by definition an intervention in markets and since a democratic mechanism decides we should intervene, one could say it’s a “positive intervention”. It’s likely that this broadness is the reason state treasury agencies are hesitant in issuing social (impact) bonds. Their core business already is social impact: building a hospital or improving the education system clearly is a positive intervention that effects people or communities.

Will the EU taxonomy provide clarity?

The EU taxonomy, that came into force on 12 July 2020, is a classification system on economic activities that qualify as environmentally sustainable. Social impact is not yet a part of this classification. The social taxonomy has been put on hold until at least the end of this parliamentary term, which is in 2024. Lack of political will and “absence of international standards” were cited as reasons it wasn’t included in the EU taxonomy that came into force in July.

However, a trading bloc as big as the EU could of course set these standards themselves and potentially urge this then to be used internationally. The Platform on Sustainable Finance, the group convened by the European Union that did the groundwork for the EU taxonomy, indeed stated that the EU should become the global “standard setter.” But that global standard, which will be there by 2024 or later, is still largely unknown.

And is the market for social bonds as big as the hype suggests?

In the meantime businesses can claim that their activities constitute ‘social impact’ and therefore raise capital directed to those activities by issuing ‘social (impact) bonds’. A risky undertaking in the sense that the public could be wary of activities that seem to be there for PR reasons only. And while companies suffer just from bad press around greenwashing concerns, investors on the other hand have been under increasing regulatory scrutiny. In May, German prosecutors a raided a financial institution on accusations that ESG-credentials in investment products were overstated. Japanese regulators are taking a similar course.

In this unknown terrain: there are still a lot of investments in social impact going on. Companies for example issued healthcare related social bonds during the Covid-years. The market share of social bonds as a percentage of total ESG debt has been significant since 2019. In 2021, over EUR 138 bn of social bonds were issued. An investment flow this big in uncertain times and on an unknown terrain, points at actual value-driven demand, other than following up on a hype.

This article is part of the Sustainaweekly of 19 September 2022