ESG Economist - Are we ambitious enough to protect nature?

In our previous note [1], we introduced the topic of nature and biodiversity loss, reflecting on what biodiversity loss could mean for the economy, households, and the financial system. In this follow-up note, we focus specifically on the European Union (EU). We examine past trends in nature and biodiversity across the continent, review key EU policies designed to halt biodiversity loss, with an emphasis on nature-related transition risks, and provide an outlook for the future.

Biodiversity across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems in the EU has steadily deteriorated due to factors such as overexploitation, pollution and climate change

The EU has developed frameworks such as the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Nature Restoration Plan…

… aiming to protect 30% of land and sea areas, restore degraded ecosystems, and enhance resilience to climate change

Despite these policies, only 26% of EU land and 12% of its sea are currently protected, with progress falling short of the 30% target for 2030

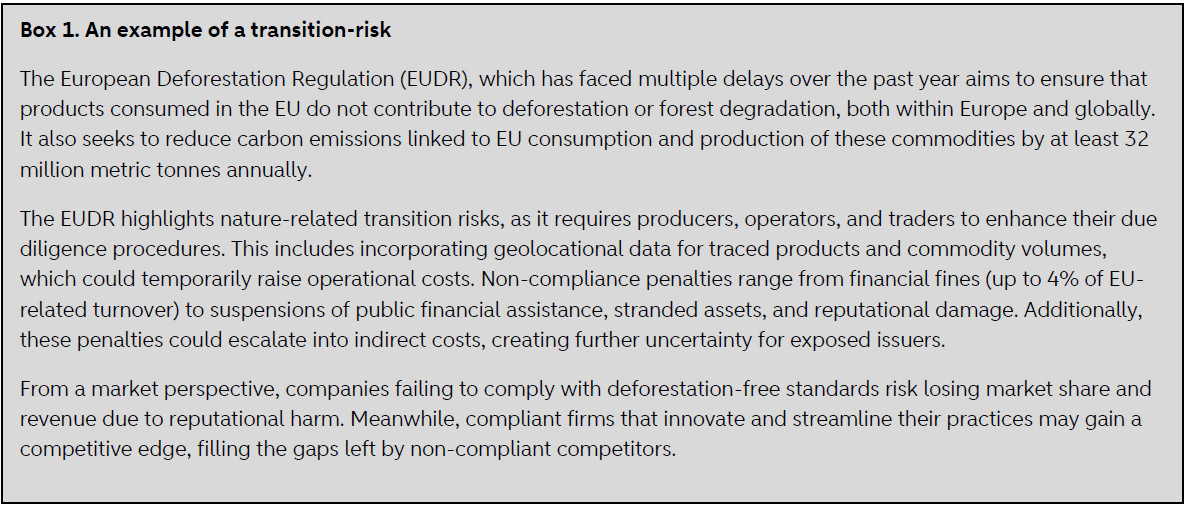

Policies such as the European Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) highlight transition risks, requiring compliance, and may increase costs for businesses

Urgent action is needed to meet targets and ensure ecological and economic resilience

Past Trends

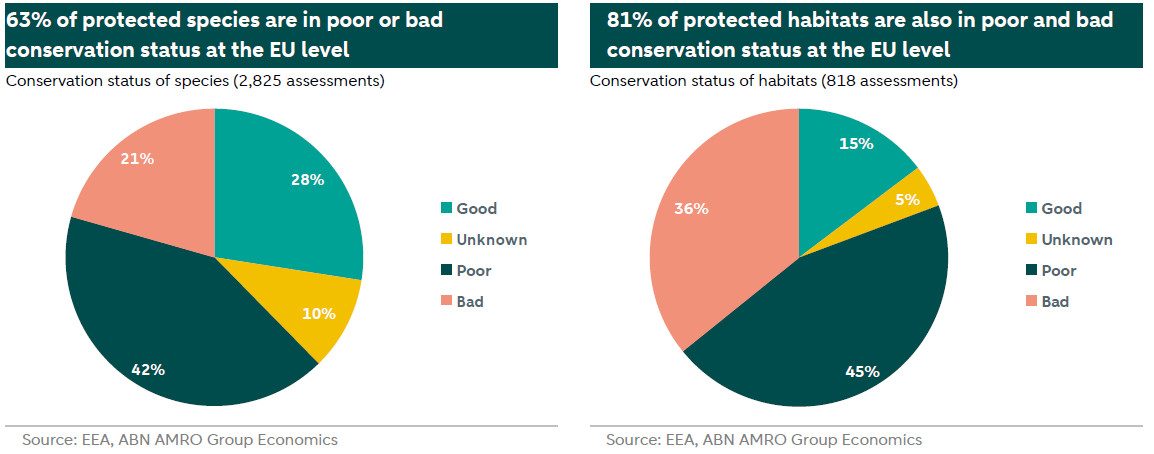

As in other regions of the world, the state of biodiversity in Europe has been steadily deteriorating. According to an assessment by the European Environment Agency (EEA) (see ), 81% of European habitats, 39% of bird species, and 62% of non-bird species that are of community interest are currently in a poor or bad state.

Long-term trends reveal similar declines. From 1990 to 2023, the index of 168 common bird species in the EU decreased by 15%. Similarly, the grassland butterfly index, which monitors the populations of 15 butterfly species – key for ecosystem services such as pollination - recorded a significant decline of nearly 30% between 2006 and 2023.

Marine resources are also under significant pressure. By 2021, only 38% of rivers, lakes, and transitional and coastal waters in the EU achieved good or high ecological status. Furthermore, marine ecosystems have continued to show alarming signs of degradation and reduced resilience, with a substantial proportion of marine mammals, fish, birds, and habitats failing to meet the criteria for ‘good environmental status.’

The state of soils is equally concerning. According to the EUSO Soil Health Dashboard, 61% of EU soils are affected by one or more soil degradation processes and, therefore, can be considered unhealthy. Soil erosion is the major land degradation process which may threaten land productivity, ecosystem services and food security. The mean soil erosion rates in EU are currently around 2.5 tonnes per hectare per year. This is much higher than the soil formation rates which is between 1-1.4 tonnes per hectare per year and implies that a major part of EU agricultural soils is degrading.

As highlighted in our previous note, the widespread poor condition of species and habitats across ecosystems is primarily driven by intense human pressures. Factors such as overexploitation of natural resources, climate change, and pollution are contributing to cumulative impacts that result in the degradation and loss of ecosystem structure and function, ultimately diminishing overall ecosystem resilience.

Nonetheless, the EU has established a comprehensive framework of environmental legislation designed to protect and restore biodiversity and habitats across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. This framework will be explored in greater detail in the following section.

What is the EU doing?

We will not cover all EU measures in detail but will focus on the most significant ones.

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 is the first comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term plan aimed at protecting nature within the EU. It seeks to halt biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems, and build resilience to climate change and other threats. As a key pillar of the European Green Deal, the strategy covers a wide range of goals and policies for biodiversity protection and restoration across the EU. Its primary objectives include protecting 30% of EU land and sea areas, with 10% under strict protection; restoring degraded ecosystems and enhancing biodiversity on agricultural land, forests, and urban areas; increasing funding for biodiversity through instruments such as the EU budget and private investments; and addressing global biodiversity challenges by positioning the EU as a leader in international biodiversity negotiations.

The Nature Restoration Plan is a critical component of the EU Biodiversity Strategy, with a specific focus on establishing legally binding targets to restore degraded ecosystems and habitats. It provides concrete mechanisms to achieve the restoration objectives outlined in the broader strategy. Unlike the overarching scope of the Biodiversity Strategy, the Nature Restoration Plan has a narrower focus on ecosystem restoration. Key goals include implementing legally binding restoration targets for specific ecosystems; restoring wetlands, rivers, forests, grasslands, marine areas, and urban ecosystems; enhancing ecosystem resilience to mitigate climate change impacts; and supporting pollinators, such as bees, through targeted restoration measures.

While the plan aligns with the 2030 goals, it also sets specific interim and long-term milestones, such as restoring 20% of the EU’s degraded ecosystems by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050. To achieve these targets, Member States are required to submit draft National Restoration Plans (NRPs) to the European Commission by September 2026. Final plans must be reviewed, submitted, and published by September 2027 to ensure compliance with the Nature Restoration Regulation (NRR) targets.

Financing for NRPs under the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) will come from both public and private sources, and Member States must outline financial needs and means in their plans. They must also address "negative subsidies"—government incentives, such as tax breaks for fossil fuels or subsidies for pesticides, which harm the environment and hinder restoration targets.

The abolition of these harmful subsidies pose transition risks for businesses as economies shift toward sustainability. These risks arise from changes in policies, markets, technology, and societal preferences aimed at addressing environmental challenges such as climate change. For example, governments may phase out harmful subsidies to meet biodiversity or climate goals, increasing costs for industries such as fossil fuels, intensive agriculture, and pesticides. Removing fossil fuel subsidies could also lead to higher energy costs, especially in carbon-heavy sectors.

Market dynamics may shift as consumers increasingly favour sustainable products, reducing demand for businesses reliant on subsidies that are harmful to nature and biodiversity. Companies that fail to adopt greener practices may lose market share to competitors. Additionally, technological risks could emerge as investments in harmful technologies, such as fossil fuel infrastructure, become obsolete ("stranded assets"). Businesses may need to invest in cleaner technologies to stay competitive, which can strain resources and profitability.

In summary, the Nature Restoration Plan sets clear restoration targets and timelines, while funding and addressing harmful subsidies remain central to its implementation. Businesses must adapt to avoid transition risks as sustainability becomes a core policy and market priority.

Other measures include the and directives, which is the EU’s oldest environmental laws that form the backbone of EU biodiversity policy and are the legal basis for Natura 2000 (a network of protected areas across the European Union (EU) established to ensure the long-term survival of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats), the directive, the (MSFD) and the . Many sectoral policies also have an important impact on biodiversity, such as the (CAP), the (CFP), the and the recent . An explanation of each is provided in the appendix.

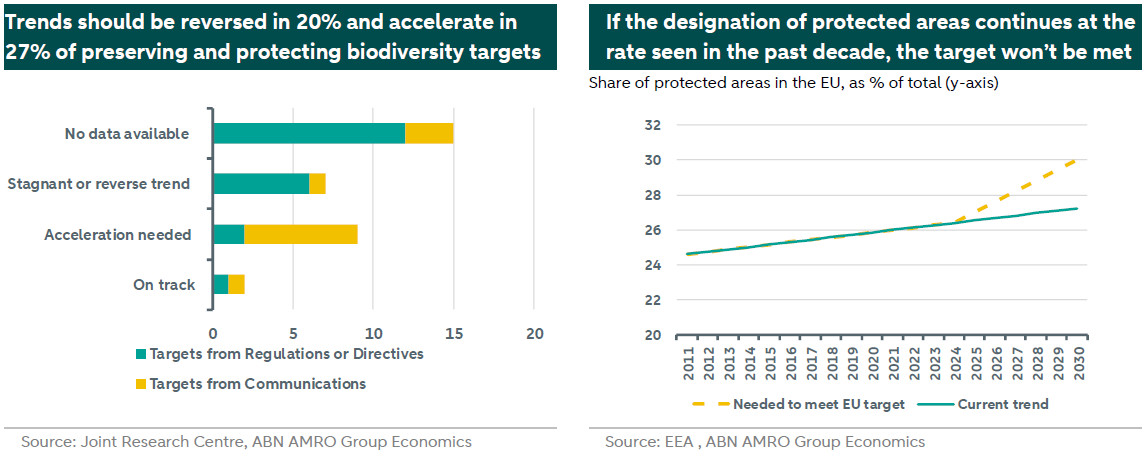

Reports suggest that Europe is unlikely to achieve its biodiversity targets by 2030. The Joint Research Centre (JRC) (see ) evaluated 33 biodiversity-related targets set by the EU. Of these, 21 are binding targets derived from the ‘Nature Restoration Law’ regulation, with the remaining 12 stemming from the Biodiversity Strategy targets. The graph below on the left shows that the JRC's evaluation indicates that only two targets are currently on track. Nine targets require significant acceleration, and seven are either stagnant or moving in the wrong direction. Additionally, for the remaining 15 targets, no data is available, making it impossible to quantify the state of progress towards the targets. This underscores the substantial data and knowledge gaps regarding ecosystem conditions and the pressures they face.

Furthermore, efforts to protect and restore nature take time to yield results, and persistent pressures such as over-exploitation, intensive land and sea use, and pollution continue to hinder progress. By the end of 2023, data from the European Environment Agency (see ) shows that protected areas covered 26.4% of the European Union’s land. Of this, 18.6% is designated as Natura 2000 sites, while 7.8% falls under other complementary national protections. However, with the current pace of progress—an increase of just 1.8 percentage points since 2011—the EU is unlikely to meet its goal of protecting 30% of land by 2030.

The graph above on the right highlights two potential scenarios for the share of protected areas in the EU. The green line represents a continuation of the current trend, projecting that by 2030 the total share of protected areas will reach only 27.2%—falling short of the 30% target. On the other hand, the yellow line illustrates the pace of progress required to meet the 30% goal. To achieve this target, the EU would need to more than double its current rate of expansion, protecting an additional 3.6% of land by 2030—an area larger than Greece.

The consequences of failing to meet these targets are significant. According to the European Commission’s 2025 Environmental Implementation Review, the financial cost of failing to fully implement EU environmental laws—due to air and water pollution, nature degradation, and inefficient waste management—is estimated at €180 billion annually, roughly 1% of the EU’s GDP. Accelerating the implementation of environmental policies could help mitigate these costs while contributing to the restoration of the environment.

Conclusion The state of biodiversity in Europe remains deeply concerning, with significant declines observed across terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. Despite the EU’s ambitious policy framework, including the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Nature Restoration Plan, progress toward key targets has been slow and uneven. Persistent human pressures, such as over-exploitation, pollution, and intensive land and sea use, continue to undermine efforts to halt biodiversity loss and restore ecosystems.

With only 26% of the EU’s land and 12% of its sea currently under protection, achieving the 30% target by 2030 will require a marked acceleration in implementation and enforcement. As illustrated in the scenarios, the current rate of designation is insufficient, and substantial effort is needed to close the gap. This includes not only increasing the share of protected areas but also ensuring that these areas are effectively managed and deliver tangible ecological benefits.

Looking ahead, meeting the EU's biodiversity goals will demand stronger commitments from Member States, improved integration of biodiversity considerations into sectoral policies (such as agriculture, fisheries, and urban planning), and enhanced investment in nature-based solutions. While the road ahead is challenging, achieving these targets is crucial—not only for the health of ecosystems but also for the resilience of the economy, households, and the financial system that depend on them. The next few years will be critical to aligning policy ambition with action and ensuring that Europe leads the way in reversing biodiversity loss and restoring nature.

In a follow-up note, we will address biodiversity and nature in various European countries, including the Netherlands.

Appendix

Habitats and Birds Directives: Protect and restore natural habitats and wild species across the EU to ensure their long-term conservation.

Water Framework Directive: Ensures the sustainable management and protection of all EU water bodies, including rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD): Aims to achieve good environmental status for EU marine waters by addressing pollution and protecting marine biodiversity.

Invasive Alien Species Regulation: Prevents and manages the introduction and spread of invasive non-native species that threaten ecosystems and biodiversity.

Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): Influences agricultural practices to balance food production with environmental protection and biodiversity conservation.

Common Fisheries Policy (CFP): Regulates fishing activities to prevent overfishing and protect marine ecosystems.

Sustainable Blue Economy: Promotes the sustainable use of ocean resources while minimizing environmental harm.

Vision for Agriculture and Food: Advocates for a resilient, sustainable, and biodiversity-friendly agricultural and food system.