ESG Economist - NZBA loosens climate ambitions

The Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) provides guidance to banks on setting climate goals. Initially, the NZBA had a key principle that banks should aim to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 and work towards transitioning to a net-zero economy by 2050. Banks committed to structure their portfolios according to these guidelines. On April 15, the NZBA released version 3 of its key principles[1]. These principles still align with the Paris Agreement, but the requirement to specifically target 1.5°C has been removed. This change gives banks more flexibility in choosing their paths to reducing emissions. In this note, we consider the potential impact of this change on emission reduction efforts.

The NZBA updated its guidelines from a strict 1.5°C target to a more flexible "well below 2°C" target

The change acknowledges the difficulty of achieving the 1.5°C goal due to current warming trends and consequently lower carbon budgets

The new targets aim to potentially allow banks from countries with higher emissions such as China and India to join the alliance…

…but raises the question whether the relaxed targets will attract new banks from high-emission countries or simply bring in banks from existing jurisdications with less ambitious climate goals

The more relaxed target has also implications for the economy, as higher temperature rises result in aggravated physical risks, leading to more losses for banks

Overall the new standard reflects a rollback in climate ambitions

NZBA loosens guidelines

The Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) has updated its guidelines. The new guidelines are no longer specifically aiming for the 1.5°C pathway but follow the Paris Agreement's goal to limit global warming to "well below 2°C, striving for 1.5°C". Previously, banks that were part of the NZBA had to set targets within 18 months of joining. Now, they are only encouraged, not strictly required to set these targets. The new guidelines also remove the "comply-or-explain" approach, meaning banks are no longer obligated to follow the guidelines or explain why they haven't. Additionally, the rules around setting targets for phasing out coal have been relaxed. The previous requirement was to state a target year for phasing out coal by 2030 for OECD countries and 2040 for non-OECD countries, or sooner. This requirement has been removed in the new version.

The NZBA's guidelines continue to require that any targets set by banks must be "science-based". This means targets should be based on scenarios, pathways, and methods from reliable sources. The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) looks at carbon budgets for global temperature increases of 2°C, 1.7°C, and 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by the end of 2100. A carbon budget is essentially the cumulative amount of CO₂ emissions that can be released without exceeding a specific temperature target. If NZBA members decide not to aim for the 1.5°C target, but still plan to reduce carbon emissions according to a "well below 2°C" path, they would likely choose the 1.7°C pathway using the IPCC's guidance. So what are the implications of a shift from a 1.5°C pathway to a 1.7°C pathway?

Carbon budget pathways

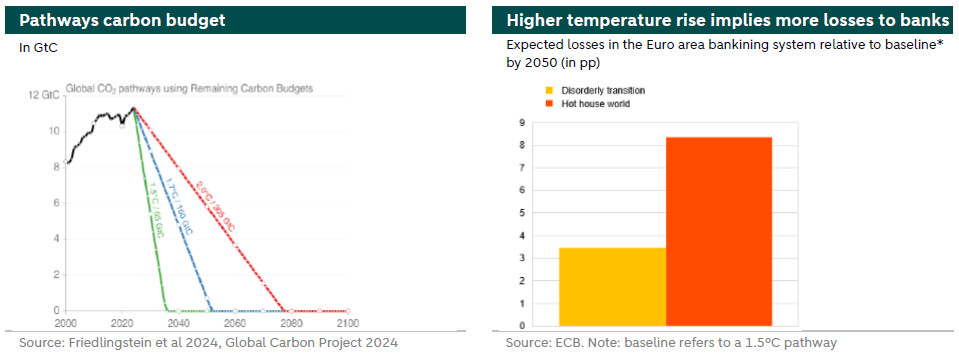

Let’s first consider the implication for emission pathways and carbon budgets for different temperature targets. The graph below on the left shows the global carbon budgets for each pathway: 65 gigatons of carbon (GtC) for the 1.5°C pathway, 160 GtC for the 1.7°C pathway, and 305 GtC for the 2°C pathway. This translates to carbon dioxide (CO2) budgets of 238 gigatons of CO2 (Gt CO2) for the 1.5°C pathway, 586 Gt CO2 for the 1.7°C pathway, and 1,117 Gt CO2 for the 2°C pathway.

The Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S, see more ) reported that in March 2025, global warming had already reached a 1.39°C increase compared to pre-industrial levels. If this warming trend continues, the C3S estimates that we will pass the 1.5°C mark by June 2029 (see chart below). This is in line with the "carbon clock” (24 April 2025, see more ) showing that for the 1.5°C scenario, only 179 Gt CO2 remained, which would last about 4 years and 2 months assuming the current pace of emissions. In contrast, there were 929 Gt CO2 left for the 2°C scenario, which could last 22 years. This means there is very limited room to stay within the 1.5°C budget. However, moving closer to a 2°C target provides much more flexibility.

Holding on to the 1.5-degree pathway?

Considering the current situation, one could question whether it still is realistic to set targets based on a 1.5°C pathway. As we explained in an earlier article (see more here), a bank that decides to pursue an ambitious (Paris-aligned) climate strategy in an environment where policymakers are rolling back on climate commitments, it could be faced by a fast shrinking balance sheet. Additionally, banks that set ambitious 1.5°C pathway targets but later have to change them due to shifts in the external environment could face reputational and operational risks. There was therefore an incentive for the NZBA to update its guidelines, allowing its members to set targets that match the current situation. This rationale also stems from NZBA’s view that “banks alone cannot solve the climate crisis” and that they act as “part of the broader ecosystem”. Hence, as “the external landscape for banks has rapidly changed, the changes adopted by NZBA are a response to this new reality”.

Consequences of moving to the 1.7-degree pathway

If banks that are part of the NZBA adjust their portfolio targets from the 1.5°C pathway to the 1.7°C pathway, the companies and sectors in these portfolios can have higher greenhouse gas emissions or greater emission intensity. This means they can follow a less strict plan to reduce emissions, allowing them to focus more on their usual business activities. That is because, as we discussed earlier, the carbon budget for a 1.7°C pathway is substantially higher in comparison to a 1.5°C pathway. Specifically, there are 586 gigatons of CO2 left for the 1.7°C pathway, while only 238 gigatons of CO2 remain for the 1.5°C pathway. This gives sectors and companies more time to reduce their carbon emissions, lowers the immediate costs and actions required, and allows the costs of decarbonization to be spread out over several years.

However, the higher degree of flexibility comes at a cost for banks and society as a whole. Moving from a 1.5°C to a 1.7°C pathway significantly increases physical risks, including more severe and frequent extreme weather events, sea level rise, ecosystem disruption and consequently, higher financial and economic losses. A 2021 study by the ECB (see ) estimated that that by 2050, banks would experience losses that are approximately 3.5% higher if global temperatures follow a pathway resulting in a 2°C increase, compared to a pathway where temperatures are limited to a 1.5°C increase (see chart on the previous page). A more recent study () also indicated that by 2030 banks could experience annual losses that are EUR 9bn higher than 2022 levels, with these losses expected to increase further after 2030 due to greater long-term transition and physical risks.

Well below 2-degree pathway is “more inclusive”

The more flexible target setting now let banks from countries with higher emissions join the alliance. According to a signatory bank (see more ), “banks from jurisdictions, like China and India, and other emerging economies haven’t joined the NZBA because the 1.5°C is too restrictive”. Accordingly, a “well below 2°C” target would allow for a “more inclusive” approach, ultimately “helping some jurisdictions to join [the NZBA]”. And indeed, as stated by NZBA, the new target “increases flexibility for banks with exposures to a range of markets and sectors to manage targets and transition across their balance sheet”.

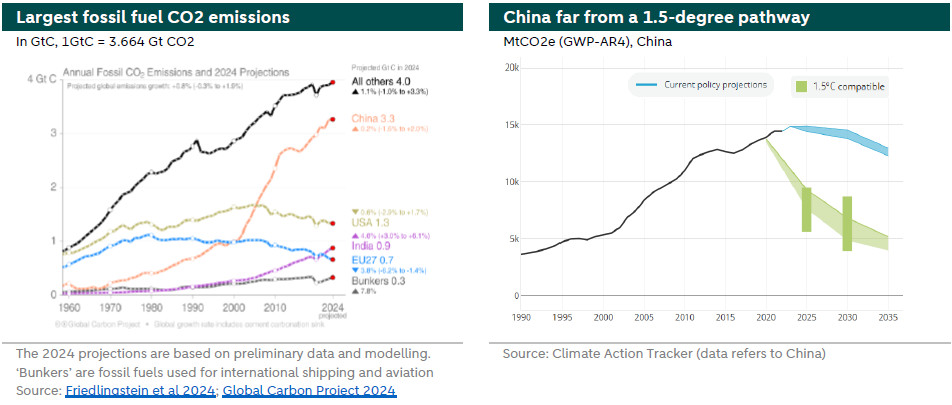

The graph below on the left shows that countries like China and India experienced a significant rise in emissions in recent years, while there was a decline in the US and the EU. Looking ahead, China and India are still far from reaching the 1.5°C pathway, as shown in the right-hand chart below. This makes it challenging for banks in these countries to set targets that match the ambitious 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement. At the same time, although the "well below 2°C" target is more flexible, it is still significantly below the current government’s trajectory. This raises the question of whether relaxing the targets will actually attract banks from these (other) countries or just allow banks from existing jurisdictions with less ambitious goals to join the NZBA.

Conclusion

The Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) has updated its guidelines, shifting from a strict 1.5°C target to a more flexible "well below 2°C" target. This change reflects the challenges of meeting the 1.5°C goal, given the current global warming trends and the rapidly changing external environment for banks. The new guidelines could attract banks from high-emission countries like China and India, because there is more room to set decarbonization targets that align with their national circumstances. However, this move raises concerns about whether it will effectively attract new members from these countries or simply allow banks with less ambitious climate goals to join. Furthermore, while the new "well below 2°C" target might be acknowledging the current reality, there are still severe implications from higher temperature rises. The new pathway significantly increases physical risks, which in turn also result in higher losses for banks. Clearly, the new NZBA standard points to a loosening of climate ambitions.