Housing market monitor - Dutch elections

The housing market is a recurring election topic because there are many conflicts of interest. Building more homes does not necessarily mean prices will fall soon. Many homeowners seem to do well even without the mortgage interest deduction. Expanding the regulated rental market costs a lot of money if we want to keep supply up.

Mike Langen

Senior Economist Housing Market

The housing market as a popular election topic

Housing is the most important election topic

On October 29th the Netherlands will once again go to the polls and choose the next government. At the time of writing we are therefore in the middle of the election campaign, in which political parties present their ideas for the future of the country. These ideas usually try to solve current social and economic problems. , most of these topics areas return every election: only a few are temporary*. For example, in the 1994 elections, pensions and social security for the elderly were an important issue, eventually leading to seats for the newly established pensioner-oriented parties AOV and Union55. In subsequent years, however, these parties more or less disappeared. Other topics are more recurring, such as economic growth, the labor market and the housing market. These topics receive special attention during every election and therefore the housing market is among the most important election topics. For two-thirds of voters, this is the topic on which they . The main problem this year is the same as so often: there are not enough affordable homes.

* We define key issues as those issues discussed by most parties in their election manifestos.

Why is the housing market always a hot topic during the elections?

The uniqueness about the housing market is that everyone participates in it and therefore has an opinion about it. Furthermore, there is almost always a structural shortage of housing because the Netherlands is a small country. Finding suitable building sites is a challenge. Construction cycles are long, averaging 10-12 years from planning to key transfer, which means that measures against a shortage will take long to show effect. And lastly, there is also a lot of money involved, which means that the government cannot simply build housing on its own but needs the help of investors. Because of these reasons, it is very important to set priorities and make trade-offs, such as: should we build more for tenants or for buyers? In addition, the Dutch housing market is highly regulated and this makes the situation even more complex. Due to the regulations, supply cannot simply follow demand but is bound by quotas (e.g. 2/3 of new construction must be affordable). In general, prioritizing one group in the market almost always leads to shortages for other groups. For example, if more housing is built for first-time buyers, there won’t be enough space added for tenants. This problem also extends across generations. Lower home prices for first-time buyers also dampen the surplus value of sitting owners. Because of these conflicts of interest, the housing market remains a major election issue.

The housing market during election cycles

The housing market has played a central role in elections for decades, but priorities have changed significantly over time. In the 1980s, the emphasis was on reducing the housing shortage through large public building programs and social renting, with a dominant role for government, corporations and tightly directed land use planning. Beginning in the 1990s, attention shifted to quality of life and urban renewal, thanks in part to decentralization and the financial housing corporations' corporatization in 1995. In the 2000s, market forces were given more room: owner-occupied housing and private land development were encouraged, while building production slumped after the 2008 financial crisis. In the 2017 elections, the emphasis was on a greater supply of mid-rent housing and more market initiatives, especially from parties like the VVD. Meanwhile, housing construction is again a political focal point, now influenced by climate commitments, migration, rising construction costs and scarce space. The debate about spatial planning and land politics - who makes building land available, at what price and for which purpose - is central to this. Thus, housing policy remains a recurring undulation between public direction and market forces.

We look at current problems and proposed measures

To remain politically neutral, we do not link measures to individual parties and evaluate the feasibility and costs of individual parties' plans (as the CPB does). Indeed, housing market policies are deeply rooted in political philosophies and are not necessarily good or bad. For example, some parties propose more regulation and/or favor social housing. From the standpoint of economic well-being, this can be good or bad, provided all measures are properly implemented. Many countries have a successful social housing sector, but many have also abolished social housing because of its high cost and added complexity. We therefore strive to remain politically neutral and inform the reader about the economic effects. Thus, we do not focus on measures proposed by individual parties, but discuss three areas: construction, mortgage interest deduction and the regulated rental market.

Building more homes

The housing shortage is increasing due to supply constraints

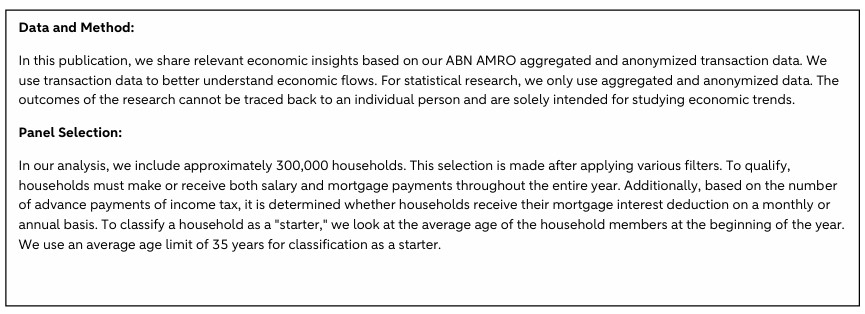

Building more homes seems to be the obvious solution to the housing shortage. Back in 2022, the Dutch government set its national housing and , with the goal of building 900,000 housing units until 2030, or about 100,000 per year. Unfortunately, this goal was never achieved, as shown in Figure 1. As a result, the housing shortage continues to grow to an expected 430,000 homes (4.8% of the market) in. There are several reasons why the set targets are not met, including long objection procedures, labor shortages, nitrogen regulations and grid congestion. The consequences are delayed building projects and increasing costs. As a result, market parties are dropping out of projects and the government is them for new investments in real estate developments.

Most parties want to stimulate housing construction, but differ on the approach

Almost all parties want to accelerate and financially support the construction of new homes. Similarly, planning processes should become more efficient where possible (less bureaucracy). However, many obstacles cannot be solved so easily (for example, grid congestion). The measures proposed by the different political parties are not very detailed, but are often limited to more money for housing and more efficiency. We see some differences in approach though, as some parties want more government control, possibly through more regulation, whereas other want fewer rules and regulations, giving the market more freedom. Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. With more regulation, the government retains control and can steer the market in the desired direction. However, creating new rules and regulations is complex and therefore takes time, especially since new rules must be enforced to have the intended effect. Sometimes, regulations can actually lead to undesirable effects. For example, the requirement that two-thirds of new construction must be in the affordable segment led to additional complications in construction projects.

More construction does not automatically mean lower house prices

Building more homes is probably the most immediate way to solve the long-term housing shortage. However, it is also the most expensive and complex way since it requires an integrated approach to regional development. New housing needs infrastructure, such as roads and utilities, and amenities, such as supermarkets and schools. The biggest problem will be to regain the confidence of investors, as many are deterred by the of Dutch politics. Because of the long construction cycle, it will take years to significantly reduce the deficit. Therefore, we don’t expect nominal house prices to fall in the coming years as a result of new construction. In a previous study, we found no relationship between housing shortages and house price growth. One reason is that a large share of the shortage consists of (social) rental homes, which will not be added to the buyers market. Another reason is that construction costs are likely only increasing, meaning new homes will not fall in price.

Abolition of the mortgage interest deduction

The mortgage interest deduction is a costly and outdated policy

The mortgage interest deduction (HRA) has been a pillar of Dutch housing policy for many years. Dutch homeowners are allowed to deduct a share of their annual mortgage interest payments from their taxable income, effectively giving them a tax relief. The policy was originally introduced to encourage home ownership. However, it is also a subsidy for homeowners, paid for by tax money and costing about 11 billion euros a year. In addition to the direct cost (loss of government income), the HRA also drives up house prices. Buyers have more incentives to buy a home and more means to pay, because their "net" payment is lower than the "gross" payment (before the HRA). Lower net housing costs increase the relative attractiveness of home ownership over renting. Therefore, buyers have an incentive to offer more money when buying a home, driving up house prices. However, the HRA also has positive effects because house prices are less sensitive to interest rate increases. Starters who are forced to buy in times of high interest rates can deduct more interest expenses than starters who bought during low interest rate periods.

Abolishing the HRA will lead to a decline in disposable income

This year’s election is special since nearly all political parties . However, this could have serious economic consequences for households and the housing market. Housing prices will come under downward pressure and, worse, homeowners (especially first-time buyers) will face higher effective housing costs. This is why most proponent parties seek to phase out the HRA over time. This involves reducing the proportion of deductible mortgage interest over a period of several years. The impact on owners would therefore gradually increase. In general, the benefits of the HRA depend on the mortgage amount, interest rate and income, but they are to 3% of net annual household income, or about 200-700 euros per month. If we assume that this benefit decreases evenly over 10 years and that wage go up each year due to inflation, the consequences are reasonably manageable.

Abolishing the HRA is unlikely to lead to falling house prices

There are two reasons why house prices may not fall with phasing out the HRA. First, phasing out the HRA over a period of several years means that buyers will be able to take (partial) advantage of it for several more years, which means that demand for housing will decline only slowly. Due to inflation and rising household incomes, it is very likely that nominal house prices will not fall at all just by abolishing the HRA. Second, the proposal of many parties is to use the additional money for lower income taxes. This could partially offset the negative effects for homeowners and buyers, even increasing effective household income. It is therefore more likely that prices will rise less compared to a scenario with HRA.

How important is the HRA really for homeowners to make ends meet?

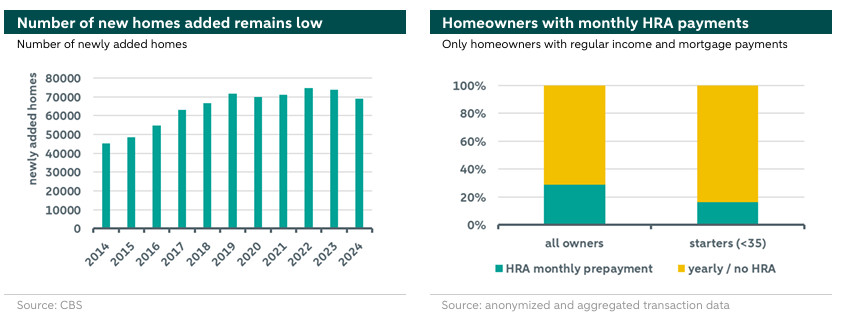

By default, homeowners receive their HRA refund along with their annual income tax calculation for the previous year. So a household that owned a home all year in 2024 will not receive the benefits of the HRA until the final tax statement mid-2025. This suggests that the HRA receipts are not needed to pay monthly expenses. However, Dutch homeowners can opt-in to receive a monthly prepayment of the HRA based on an estimate of the final tax payment the following year. Any differences between the estimated and actual tax payment are then settled the following year. Since the prepayment does not take into account the taxation of assets, this option makes the most sense for households with few other assets (e.g., stocks) and relatively stable incomes, such as first-time buyers*.

* Otherwise, households would have to pay back most of the prepayments the following year

Many households seem to do well without monthly HRA payments

Using anonymized and aggregated bank transaction data, we examine how many households choose to opt into monthly HRA prepayments, possibly because of their dependence on them. We focus our analysis on households with regular mortgage payments and salaries (not self-employed or pensioners). We find that in 2024 (2023), 29% (31%) of homeowners in our sample chose for the HRA prepayment option. Surprisingly , these households have higher median household incomes and higher mortgage payments. When we look at the ratio of mortgage payments to income, we see that they are also slightly higher. Among first-time buyers (<35 years old), only 16% received the monthly prepayment, although this group generally has much higher mortgage expense ratios than older households. These findings suggest that many homeowners can pay their monthly mortgage payments without the HRA discount.

Regulation of the (social) rental market

The Affordable Rent Act expands the regulated rental sector

On July 1, 2024, the went into effect. As a result, homes up to 186 points in the housing assessment system (WWS) are subject to a maximum rent of 1184.82 euros per month (2025). These homes are just above the social housing segment and the goal is to keep rent affordable also for middle-income households. In essence, the law expanded the regulated housing market by increasing the number of rental properties covered by rent regulation, further limiting the free rental market. Since this limits future rental income while house prices are at record highs, many investors have therefore decided to sell their investment properties. As a result, supply in the middle segment of the rental market (up to 186 WWS points) is currently decreasing. Few political parties have announced plans on the future of the law, indicating a preference to stick with it. Only a few parties have announced plans to either expand the law (more regulation), or abolish/bypass it (less regulation). In addition, most parties want to give more support to social housing corporations through lower taxes or other financial support, strengthening the regulated rental market.

A regulated rental market can cost the government a lot of money

A well-regulated rental market can help prevent speculation and thereby keep prices affordable. However, given the current housing shortage and high house prices, further expansion of the regulated rental market requires extensive financial support. This applies to social housing, but also to the middle segment. The Dutch government initially scaled back its investment in social housing corporations in 1989 in order to save money. This went well, but since the restricted the activities of housing corporations, they have been struggling financially. Especially with land prices and construction costs rising, it is impossible to build social rental housing in some regions without external financial support. The problem is that if rents are regulated, rental income is low and so is the return for developers or corporations. Sometimes the development costs (land + construction) even exceed the potential revenue. Therefore, social housing companies receive benefits in the form of lower taxes or subsidies, making the calculation positive. But building land is increasingly owned by municipalities, leading to conflicts of interest between municipalities and the state. Free market parties, currently dominating the middle segment, often receive less support. They sometimes build affordable housing units without profit (because of the quotas) and then recoup their profits from the free market housing units. This drives up prices in the free segment and can only be prevented with government money. Overall, rent control is costly if we also want to ensure that supply remains high. Otherwise, supply will decrease (as it currently does in the middle segment of the rental market), which will be felt by future generations.