US Watch - Why tariffs will not unleash the next inflation wave

We evaluate whether the initial tariff-induced inflationary shock could once again transform into a persistent inflation wave. The trade war could cause supply chain disruptions again, although after the de-escalation this is less likely. Export restrictions remain a threat. The US is already facing a negative labour supply shock, but it’s mostly absorbed by weaker demand. The lack of stimulus from the Big beautiful bill is a blessing in disguise, as more demand-inducing spending would be inflationary. While some circumstances are similar to those that led to the 2020-2022 inflation wave, they represent minor ripples, not the perfect storm. We highlight two alternative channels that could lead to inflation picking up again.

The US economy is waiting for the tariff inflation shock to hit. In the June press conference, Fed Chair Powell noted that they were not sure yet whether tariffs would be a one-off shock or could lead to another wave of persistent inflation. With the previous inflationary period fresh in everyone’s minds, and fears clearly setting in – as evident in survey evidence on inflation expectations - it’s helpful to outline how inflation could run out of control again. The biggest worry is of a wage-price spiral, where higher prices lead to higher wage demands, which contribute to further price hikes. We’ve recently written about how such a scenario remains unlikely in the US. This was also not what caused inflation to run out of control in the past few years. Back in 2020-2021, there were at least three factors that increased the persistence of the initial shock. First, supply chain disruptions were persistent leading to goods inflation. Second, a persistent negative labour supply shock first increased goods inflation and later services inflation. Third, substantial stimulative fiscal and monetary policy responses boosted aggregate demand, leading to both goods and services inflation. To what extent is the current constellation of the US economy a breeding ground for these tariffs to turn into another persistent inflation wave?

While some tariff-linked inflation is already visible, you do need a magnifying glass.

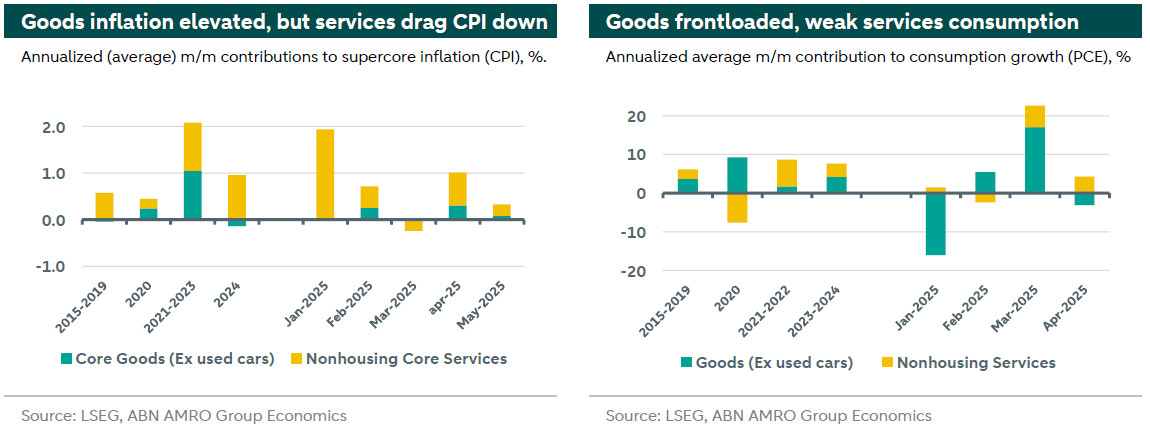

Our model-based estimate of the impact of tariffs actually implemented as of today would imply a core PCE impact of about 0.9 pp. The reality has been much milder until now. Core goods CPI prices have risen by 0.15% between January and May this year. This contrasts with an average -0.10% 4-month inflation over 2015-2019. ‘Excess’ core goods inflation is therefore about 0.25% until now, and it can be directly tied to tariffs as inflation is higher in tariff exposed categories. At the same time, core goods represent only 25% of the overall core basket, meaning the headline impact is still a second decimal story.

What is perhaps more interesting is that this moderate increase in core goods inflation has been accompanied by unusually weak services inflation, partly driven by energy prices – which indirectly feed into some core measures such as airfares - but also driven by lower demand in some categories. This was not directly foreseen in our models, and also unlikely directly attributable to the tariffs, but rather a longer-term trend of more vulnerable consumers, exacerbated by unprecedented levels of policy uncertainty. That should also make us wonder about the proper counterfactual for goods inflation, as it might have jointly declined with services inflation otherwise. Tariffs might therefore already have had more of a price impact than the ‘excess’ 0.25% referenced earlier, although nowhere near the 0.9% suggested by our tariff impact model.

What is causing the delay in goods inflation? There are several reasons why we should not expect immediate price increases. Exporters, importers and retailers can absorb part of the tariffs in their margins. Moreover, as the Q1 GDP report showed, private inventories in Q1 rose by an amount that usually takes a full year. Facing uncertainty about whether tariffs will be there tomorrow, companies may therefore choose to wait to lock in big price changes until they are forced by declining inventories that contain an increasingly large share of tariffed imports. Higher household inflation expectations – University of Michigan one-year inflation expectations stand at 5.1% - make it easier for companies to pass through higher costs to consumers. At the same time, businesses are finding various ways to avoid the tariffs, as discussed in our latest global monthly. All-in-all, it is still likely that we’ll see core goods inflation shooting up over the summer, but demand effects are increasingly appearing to lower the ex-tariff inflation path. However, inflation is clearly not only demand driven – in fact, the month with the greatest increase in core goods spending saw the lowest core goods inflation - and supply plays an important role.

Tariffs can cause significant disruptions to the supply chain, but retaliation is the bigger risk.

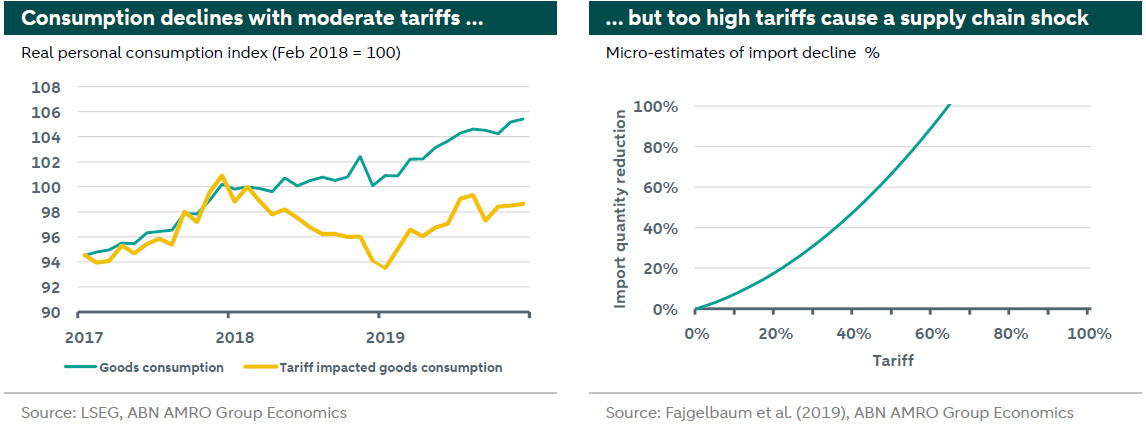

The consensus view is that tariffs increase prices and decrease demand. Looking back at the consumption data in response to tariffs in the first Trump administration, we observed a roughly 4% relative price increase, and a 7% growth differential in real consumption growth for tariff-impacted vs non-impacted goods. Still, the tariffs were not sufficiently widespread to make a real dent in either inflation or consumption. Clearly, that’s different this time.

Higher prices naturally dampen demand, but the degree to which is highly dependent on the level of the tariff. Using an extensive dataset on product-level tariffs and import quantities from Fajgelbaum et al. (2019), we estimate the expected decline in imports six months after the enaction of new tariffs, as a function of the level of tariffs. The analysis reveals a non-linear drop in imports in response to higher tariffs. A 10 or 20% tariff may be absorbed and dealt with, but tariffs exceeding 60% effectively put a full stop on imports. The level of tariffs therefore determines whether we’re in a 2020-type world where goods are simply not available, or a 2021-2022 type world where they are available, but very expensive (see also the inflation and consumption charts above). Ironically, in an extreme case higher tariffs might therefore actually lead to lower inflation. As goods become so expensive they’re no longer available or consumed, the drop in their consumption-weight in the inflation basket largely offsets higher prices.[1] With current developments in the tariff negotiations, we appear to be more likely to be in a world where most goods are available, but simply expensive, which will impact headline inflation.

Tariffs are therefore unlikely to cause a repeat of the persistent supply chain problems of the pandemic aftermath. Instead, we’re more likely to see them being caused by retaliation to tariffs in the form of export restrictions. We’ve written before that the US started the trade war ill-prepared, unable to produce the goods on which it is restricting imports. An even bigger challenge however is when trading partners decide themselves to restrict exports to the US. In particular, China has a near-monopoly on the export of rare earths which it is using extensively to pressure the US and the world. Indeed, the export of these, and other key products, was the main topic of the second round of trade talks between the US and China in London earlier this month. Rare earths are key inputs for various high-tech industries, ranging from electronics, EVs to defence. China has now changed its exporting regime to one of short-term licencing, meaning this will remain a vulnerability indefinitely.

A labour supply shock is already happening.

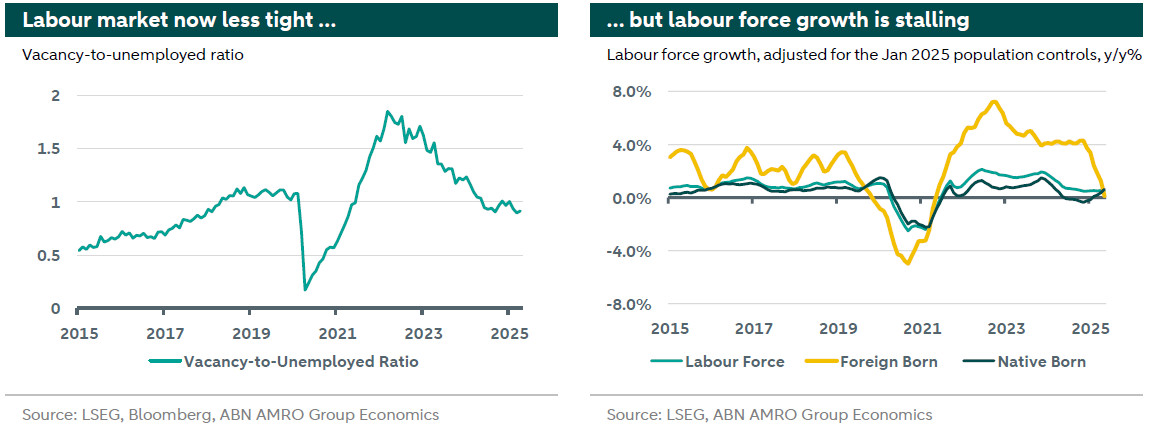

The post-covid period saw a historically tight labour market. As the overall labour force growth in the chart on the right below shows, not all people that left the labour force returned once the economy re-opened. This led to a situation where the vacancy-to-unemployed ratio stood above one for multiple years, putting pressure on particularly services inflation. Organic labour force growth has remained relatively low since then, averaging about 0.7% per year since the second half of 2021. Rather, the tightness in the labour market was ultimately alleviated trough unprecedent growth in immigrant labour, attracted by the prospect of abundant and well-paying jobs. This has now stalled. This partly reflects tighter immigration policy in the final months of Biden’s presidency and a gradual weakening of the labour market, but it accelerated further under the Trump administration. This is not a story of the ICE deportations that are all over the news, but mainly one of lower immigration through deterrence.

The current reduction in labour supply growth to some extent coincides with a reduction in labour demand growth, which limits the impact on labour market tightness, something that we anticipated last summer. The annual growth in non-farm payrolls has steadily declined since the post-covid recovery, from an average of 3.6% per year between the second half of 2021 and end of 2023 to 1.1% as of today. This is slow, but not worryingly so; the 2015-2019 period saw an average annual growth of 1.7%. We don’t see jobs growth falling into negative territory. Still, sectors that are more immigrant-dependent are exactly the ones where labour is already scarcer, meaning that although we may not see the overall tightness that we saw in 2022 and 2023, we may see more localized tightness, with also more localized inflationary pressures.

The timing of the tariff shock also coincides with a fiscal impulse from the Big Beautiful Bill, but it’s unlikely to have a strong stimulative effect.

A large part of the inflation of 2021-22 was ultimately demand driven, caused by various grants to business and household stimulus cheques, combined with large fiscal spending bills such as the CARES Act in 2020, the American Rescue Plan and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Acts in 2021, and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. Jointly these added about $6 trillion in fiscal spending through transfers to families, businesses and investment in infrastructure. Most of these tax dollars were therefore spent in areas that really stimulated demand. These came on top of the demand impulse generated from accommodative monetary policy by the Fed, as well as pent-up demand from lockdown-induced excess saving.

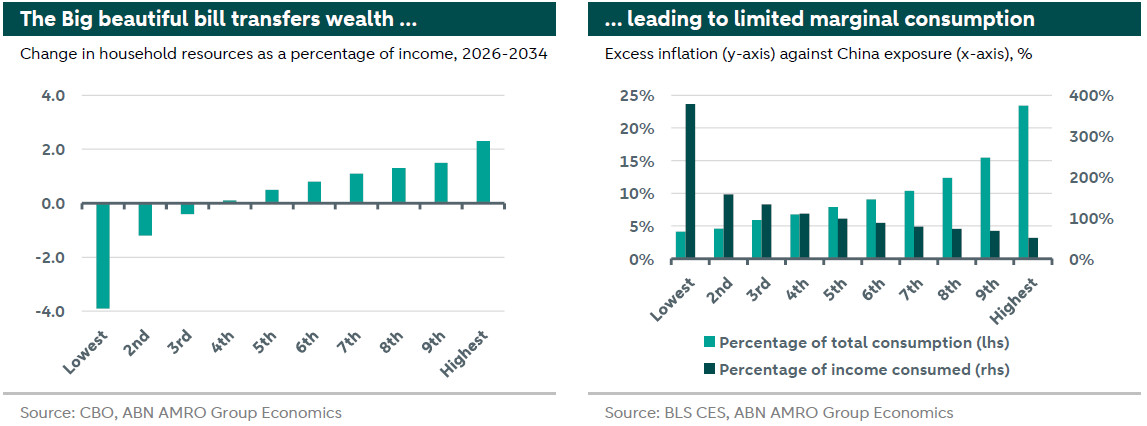

The Trump administration uses the argument that tariffs bring lots of revenue and can therefore offset tax cuts elsewhere, linking the tariff and fiscal shocks. Despite an unprecedent fiscal impulse, almost as big as the four 2020-2022 acts together, the Big Beautiful Bill Act is unlikely to create a lot of demand however. The primary reason is that a large part of the tax bill represents an extension of currently applicable tax reductions. The extra fiscal spending is therefore better regarded as the absence of a tightening fiscal shock, rather than a stimulative fiscal shock. Second, the tax has large distributional implications that make it unlikely that consumption will pick up rapidly. As the left hand side chart below shows, after-tax income will drop significantly for the lowest income households, while rising for the median household and above. The households that get a tax break do represent the highest share of consumption, with the top half of earners consuming about 71%. (The figure is more striking in terms of wealth, where the top 10% wealthiest Americans account for half of consumption). Still, by and large the households that get a tax break are not really constrained, as they already consume less than their full salary, and often significantly less. On the other hand, the lowest income households have to dissave or borrow to support their consumption. They are likely to be more constrained if and when the bill goes through, and will have to decrease consumption.

The risk of the inflationary shock turning into a persistent inflation wave along the channels we saw in 2020-2022 is therefore limited.

The current level of tariffs is unlikely to cause big disruptions in supply chains. Still, a re-escalation is still a real possibility, and we might see tariffs again that would be observationally equivalent to persistent supply chain disruptions. As of now, there is no shortage of labour, because the drop in supply is mostly absorbed by the drop in demand. This limits both the risk of a tight labour market, and the risk of high unemployment. The Big Beautiful Bill increases spending significantly relative to current legislation, but not relative to current spending, and is unlikely to significantly stimulate demand. We therefore effectively expect the tariff-induced inflationary shock to be, dare we say it, transitory. However, a Fed that takes such a transitory shock at face value and simply decides to ease may be up for an unpleasant surprise. Additional demand-driven inflation comes on top of the tariff inflation, and may amplify the latter. Moreover, the demand impulse stemming from monetary easing may heat up the labour market again in a context of limited supply, increasing wage pressures, further supported by increasing inflation expectations on the back of the Fed actively allowing inflation to creep up again. It doesn’t really matter where the stimulus comes from - fiscal or monetary - both could steer inflation of the narrow transitory path.

The fact that, despite some parallels, the 2021-2022 channels are unlikely to reignite inflation does not mean there is no risk of a new big inflationary wave.

Rising inflation expectations and reckless fiscal spending still present inflationary risks. Anticipatory inflation expectations have risen, with consumer 1-year expectations exceeding the peak in 2022, while market-based measures are now reaching levels as seen in 2021. Higher inflation expectations may be a self-fulfilling prophecy. that households consume more durables when they expect the price to go up, with higher demand driving up prices, although we’ve yet to see this in this round. Second, they play a role in wage setting or deciding on hours worked. Third, when consumers expect higher prices, it may be easier for firms to raise prices. In the current context, it may be especially easy considering the price shock is seen as external to the firms.

A second major upside risk to inflation is the US’ debt stock, whose trajectory will be significantly worsened by the Big Beautiful Bill. It seems unlikely this administration will do anything to bring the deficit back to a more sustainable level, and as such the debt-to-GDP level is set to rise. Default remains unlikely, but a sudden increase in medium- and long-term interest rates, through a combination of higher inflation expectations and risk premia, are not unlikely, and effectively something we’ve already seen over the past months. We’ve written previously that one of the ways the US may deal with its higher debt levels is to simply inflate its way out of it. An independent Federal reserve is unlikely to lower interest rates just to make the debt more sustainable. We generally maintain the view that it is unlikely that the current government will be able to concretely control the Fed. Rather, ‘fiscal dominance’ might occur through financial stability channels. If interest rates get out of hand, the Fed’s financial stability mandate may overcome its monetary policy mandate of maintaining stable prices. This could force even an independent Fed to effectively start monetizing debt by buying up Treasuries and/or lowering rates. Not a good prospect, and certainly not for inflation.

With both of the channels above, it’s important to note that these are risks to the inflation outlook, not baseline predictions. That being said, the set of circumstances, with elevated inflation expectations and increasing attention to an out-of-control debt trajectory mean that the probability is certainly higher than it was a mere half year ago.

[1] Indeed, the component weights in the PCE price index are updated monthly, and therefore quickly capture the changing composition of spending (including consumer’s substitution towards cheaper items).