Global Monthly - Bracing for impact

The tariff deals the US struck over the summer have averted a worst case scenario for the global economy. The impact of tariffs remains uncertain, and depends on how, when and where businesses pass on the tariffs to consumers. We have modestly downgraded our eurozone growth forecast as tariff rates came in somewhat higher than the base case. Stronger domestic demand is helping, amid US and China weakness.

Global View: With deals now struck, attention is shifting to how much impact US tariffs will have

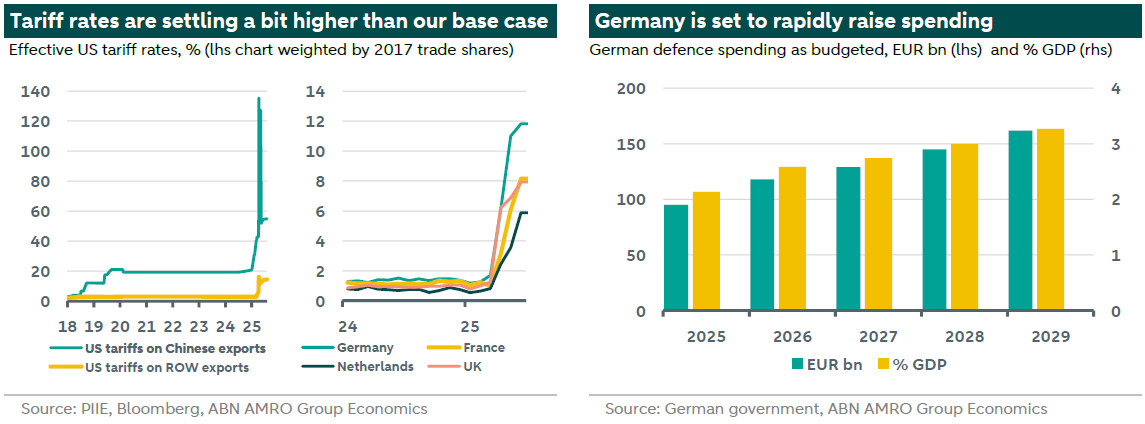

After six months of tariff drama, the contours of the US’s new trading regime are coming into view. Frameworks – to the extent that they stick – have been signed, and US tariff rates are generally somewhat higher than expected, although not catastrophically so. Now that agreements have been struck and we know what we are dealing with, the focus is shifting to what kind of impact the tariffs will have. US tariffs will still act as a significant dampener on the global economy, but they are unlikely to cause recessions. Still, the nature of the shock is unprecedented in modern times. On the one hand, the shock to global trade could be bigger than we forecast, with unforeseeable nonlinearities. On the other hand, if we see more extensive/sustained ‘spreading of the pain’ by multinationals or by exporters to the US in order to limit demand effects, the impact could be milder than we forecast. Tariffs aren’t the only game in town of course. Whether Russia and Ukraine make peace or not, Europe looks determined to significantly raise defence spending over the coming years [1], which is expected to start lifting growth in 2026. In the US, immigration policy is also playing a key role in shaping the impact of a slowing economy on the labour market, and in turn its effect on inflation and Fed policy. And in China, while exports have been resilient in the face of US tariffs, the government is still struggling to stimulate weak domestic demand amid a four-year long property bust. As we brace for the tariff impact, attention is also likely to increasingly shift to new economic drivers.

Trade deals turned out a bit worse than our base case, but not alarmingly so

In line with our expectations in the last Global Monthly before the summer break, the US ended up agreeing tariff deals in July and August with its biggest trade partners, averting a damaging escalation and renewed uncertainty over the outlook. Broadly speaking the US has divided the world into three buckets: 1) developed markets, whose goods face a baseline tariff of c15% when entering the US[2], 2) emerging markets[3] ex-China, with a higher tariff of c20-30%, and 3) China, which faces an effective tariff of c40%. Alongside these country specific tariffs, there are higher tariffs for certain sectors such as steel & aluminium and cars, though here as well, there are numerous carve-outs. Meanwhile, around 1/3 of US imports – including consumer electronics, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors – remain entirely exempt of tariffs, at least for the time being. Tariffs are still far from universal.

As each other’s biggest trade partners, the most consequential of all the agreements was that between the US and the EU on 27 July. Ultimately, the EU agreed to accept a 15% tariff on most of its exports to the US, with some key exemptions for aircraft and certain chemicals. This 15% rate was higher than our base case expectation for a 10% tariff, though the difference is blunted by 1) the fact that the 15% no longer ‘stacks’ on top of pre-existing (most-favoured nation) tariffs, 2) a 15% tariff ceiling for key sectors such as cars (was 25%), as well as pharmaceuticals – which are currently exempt but where much higher (as much as 250%) tariffs have been threatened.

Taken together, while worse than our base case, the EU-US trade deal was by no means catastrophic, and is unlikely by itself to tip either side into a recession. We have made a downgrade to our eurozone growth forecast for next year, though this also reflects two other important factors that have come to light in recent months: 1) that the frontloading of exports to the US at the beginning of the year is unwinding more slowly than we thought it would, and 2) that businesses seem to be taking longer to pass tariffs on through supply chains and to consumers. These factors slightly raise our 2025 growth forecast to 1.2% from 1.1%, while taking our forecast for 2026 back down to 0.8% from 1.1% previously[4]. In quarterly terms, we expect q/q growth to stay below trend in the near term, before picking up towards the end of the year.

Impact of trade tariffs appears to be unfolding more gradually than expected

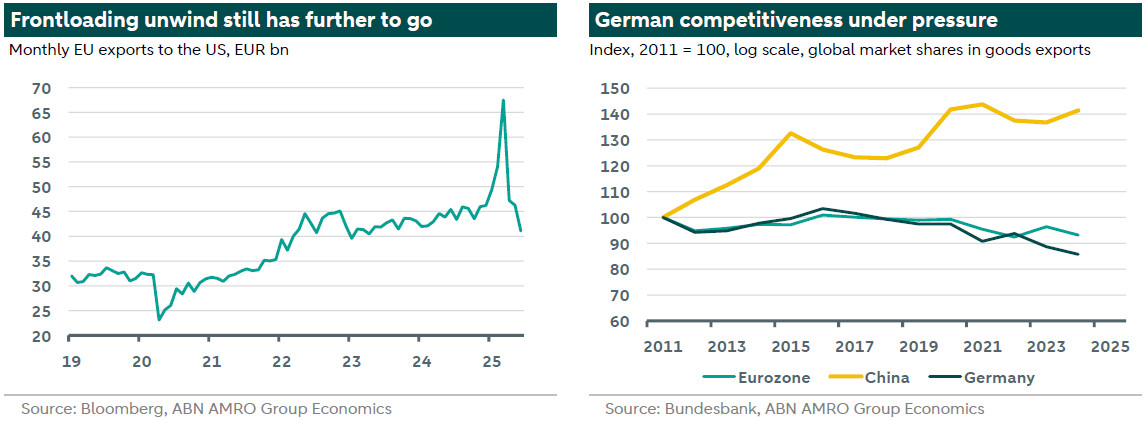

First, on the unwind of frontloading. While European exports to the US fell by some 42% from March to June, this followed an extraordinary spike in exports in Q1, as exporters tried to get ahead of the tariffs implemented in April. Current levels of exports represent a mere normalisation rather than full payback for the earlier jump. Assuming US inventories are not now kept permanently higher, a further fall, or extended slump, in exports looks unavoidable. We suspect that different dynamics in different product categories explain why frontloading has not fully unwound yet. For instance, given that tariffs on pharmaceuticals have yet to be implemented (they are subject to a Section 232 investigation, which is due to complete in November at the latest), some frontloading is probably still happening in this category, offsetting bigger declines in other categories. This softens the blow of the frontloading hangover.

Second, anecdotal reports (see eurozone) suggest that European multinationals with subsidiaries in the US view tariffs as a hit to margins rather than a reason to immediately raise prices. Over time we expect businesses to recover their margins by raising prices. This will depend crucially on the consumer demand environment in the US, which is looking fragile of late (see US). Still, the ability of businesses to absorb some of the tariff rise – even if temporary – helps to dampen the demand shock. Another means by which the demand shock might be managed is if businesses opt to implement small but global price rises rather than concentrated, big price rises in the US. The latter would likely induce a much bigger demand shock. This would seem to incentivise multinationals to ‘’spread the pain’ if anything. Indeed, the fact that eurozone demand is strengthening just as US demand is weakening would also work to encourage this type of response.

Still, the tariffs could not come at a worse time for the European – especially German – export industry. In trade-weighted terms Germany is the hardest hit of the major eurozone economies, with an effective tariff rate of almost 12% as of June (see chart on front page). But tariffs are just the latest setback for German exports. According to Bundesbank estimates, Germany’s market share in goods exports have fallen since 2017 and have been particularly weak since 2021, especially in machinery and energy-intensive industries. High energy prices and structural factors like bureaucracy and demographics are major drags. More recently, the stronger euro has presented an additional challenge, and we expect further euro strength next year (our end-2026 forecast for EUR/USD stands at 1.26). But most important has been China going from a source of [RQ1] demand for German exports to a competitor – even in home markets (see chart above). This looks unlikely to change dramatically in the near-term, with the Chinese authorities still struggling to resuscitate consumer demand. All told, the combination of US tariffs and competitiveness pressures are likely to continue weighing on the eurozone external sector at least through 2026.

Eurozone domestic demand saves the day, amid US and China weakness

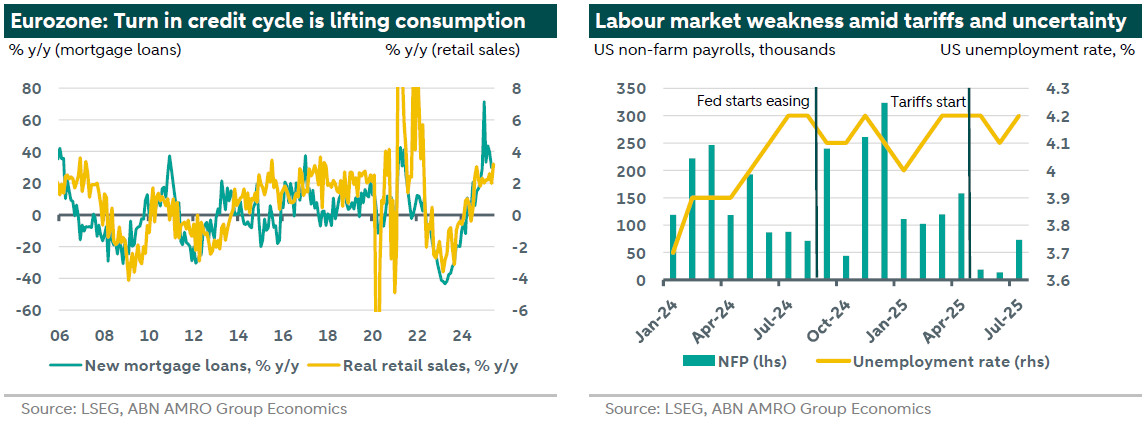

By almost lucky coincidence, eurozone domestic demand is strengthening, helped by ECB rate cuts, and an upturn in the credit cycle (see chart below). Domestic demand is likely to strengthen further as Germany starts spending its fiscal bazooka. Higher defence spending in particular is likely to give industry a much needed new source of demand, just as export markets continue to soften. Germany plans to raise defence spending to 3.5% of GDP by 2029 – far ahead of the NATO target of 2035 (see above). German infrastructure spending is also set to rise more quickly than we originally expected. The more accelerated opening of the German fiscal taps is one of the main reasons we no longer expect the ECB to cut rates further.

Elsewhere, our base case is largely unchanged. In the US, underlying growth has already slowed considerably (as we discuss in the US section), and we expect further weakness as tariffs are passed on to consumers, depressing real incomes. An additional drag is coming from the softening labour market. All told, US growth is expected to stay well below trend over the next year, only picking up towards the end of 2026. A key uncertainty is when the Fed starts to cut rates. As we discuss in our Spotlight next, this is highly dependent on the data flow of the coming weeks, and US data has so far failed to paint a clear and convincing picture in either direction. And in China, we expect the authorities to step up stimulus, with recent weakness in data likely increasing policymakers’ sense of urgency. However, this is likely to be more about limiting the downside rather than sparking a new boom: we still expect (annual) GDP growth to slow in 2H-2025.

[1] Either way, Europe is unlikely to go back to importing Russian gas on a large scale.

[2] The UK, Australia and Singapore face a lower 10% tariff, likely reflecting that they have a trade deficit rather than a surplus with the US.

[3] India and Brazil are notable exceptions, which face higher tariffs. For India, this is linked to its oil imports from Russia, and Brazil due to the treatment of former President Bolsonaro.

[4] This brings us full circle back to our Global Outlook projections last November. While tariffs have surprised negatively since then, German government spending plans have surprised positively, and these two factors can be thought of as broadly offsetting.