Spotlight - Geopolitical risk is back with a vengeance

Geopolitical risks have flared up in a dramatic fashion at the start of the year. We present a framework to analyse the main channels of impact for the economy. The Greenland dispute risks escalating economic warfare between the EU and the US and an undermining of NATO, while the risks surrounding Iran revolve around oil supply. Threats to Fed independence could destabilise inflation expectations, but Chair Powell remains defiant.

Geopolitical risks are flaring up

Just as it looked like geopolitical risks were starting to ease, they flared up in a dramatic fashion at the start of the year. From Venezuela to Greenland to Iran, the geopolitical hotspots are multiple. President Trump has re-stated his view that acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States. This has now been backed with coercive tariff threats against European countries in order to achieve that objective, and the White House has said that ‘utilising the US military is always an option’. This comes against the background of the capture of Venezuelan President Maduro at the start of the year. This was seen as a demonstration that the Trump administration is willing to use military power to achieve its objectives and that international law is not at the forefront of its considerations.

Various other Latin American countries appeared to be at risk of a similar fate, but the most prominent threats recently have been in the direction of Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, which is a member of both the EU and NATO. Protests in Iran against the regime have also been significant. President Trump had encouraged protestors to topple the country’s institutions, while also suggesting the US could intervene militarily. As if all this was not enough, we have also seen fresh threats from the US administration on the independence of the Fed. The Fed has received grand jury subpoenas from the Justice Department regarding renovations at its headquarters, with investigations centred on ‘possible taxpayer abuse’. Before tackling the various flashpoints, we turn first to a simple framework for analysing the impact of geopolitical shocks on the economy.

Four main channels of impact

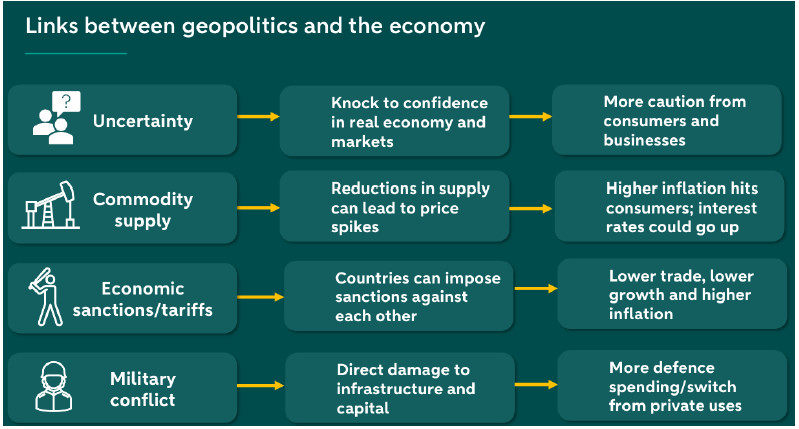

Below, we identify four main channels of impact from geopolitical shocks to the economy:

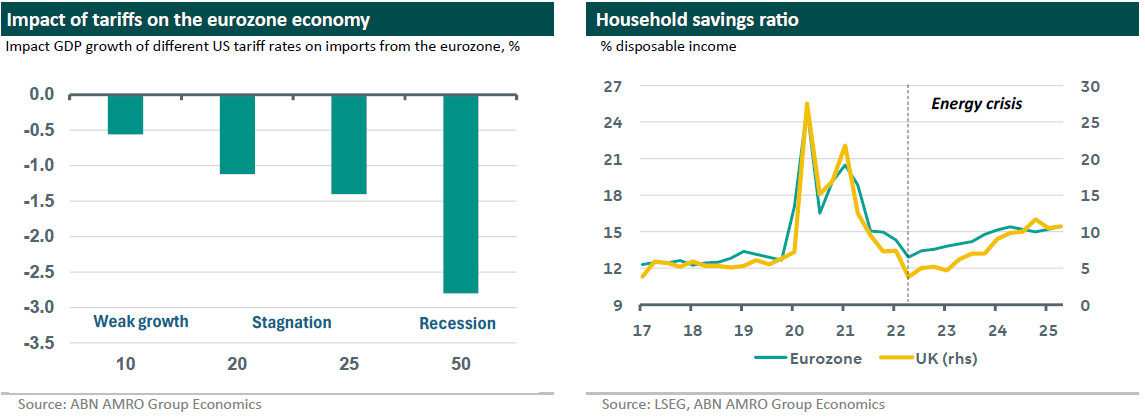

First, higher uncertainty can knock confidence in the economy and markets making businesses and consumers more cautious. Households would tend to spend less and save more. A good example is in the eurozone, where the household savings ratio picked up again following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and remains well above its pre-pandemic level. It is a similar story for companies, which would tend to hold off from capital spending. Uncertainty can also stem from the undermining of domestic and international institutions as they tend to provide more predictability about the future. For instance, independent central banks provide more confidence in future inflation, fiscal rules in the future sustainability of government debt, while internationally, NATO provides more confidence in future security.

The extent and duration of uncertainty of course depends on the other potential channels of impact. Traditionally, geopolitical risk impacted the economy because the countries involved were oil producers. Fears of supply disruption lead to higher oil prices, meaning higher inflation, less consumer spending and sometimes higher interest rates. Furthermore, countries in conflict can impose sanctions or tariffs on each other, and we have of course seen that up close over the last year. As a rule of thumb, a country imposing tariffs or sanctions is imposing a supply shock on its own economy, which means lower growth and higher inflation, while it is more of a demand shock (both lower growth and inflation) for the country on the receiving end. Finally, actual military conflict has obviously very direct destructive effects. As well as loss of lives, war also destroys infrastructure and the capital stock more generally and sees resources shifting from the private sector to the military effort. It hence reduces the productive potential of the economy where the conflict is occurring. The spillovers to other countries then depends on the size of the economy and the strength of trading links.

Greenland could lead to escalating EU-US economic warfare

President Trump has strongly asserted that acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States. This has now been backed by against European countries in order to achieve that objective, and the White House has said that ‘utilising the US military is always an option’. Europe has been steadfast in its response, with a joint statement from European leaders making clear that ‘Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland’. Thinking purely of the impact on the economy, three factors matter. First, whether this dispute leads to unleashing of sanctions and/or tariffs between the US and the EU, that could have negative impact on both economies. In this respect, the US has fired the first shot, with president Trump saying he would impose additional tariffs of 10% on European countries from next month until they agree to support his administration’s ambition of acquiring Greenland.

A 10% tariff – if sustained and if across all eurozone exports – would over time reduce eurozone GDP by 0.5% according to our calculations. However, it is worth noting that so far US tariffs have not been imposed on all products (with for instance pharma being an important exception). So, effective tariff rates have tended to be 2/3 of the headline rate. That would mean a GDP impact of around 0.3% and again assuming the tariff rate holds over the long term. While last year the EU took US tariffs on the chin, i.e. it did not retaliate, history may not repeat itself this time. Europe seems to have drawn a line with regards to Greenland and appears to be less open for appeasement. According to reports, EU leaders are preparing a package of tariffs affecting EUR 93bn of US imports and/or restricting US companies from the internal market under the anti-coercion instrument (ACI). This could give the EU leverage in future negotiations on Greenland, though it also risks a further escalation, with the US potentially raising tariffs further. Whether Europe continues to stand firm is a question mark.

A second factor to consider is the impact of this heightened uncertainty on business and consumer confidence, which could lead to a dampening of domestic demand. Our base scenario for the eurozone economic recovery partly relies on a return of ‘animal spirits’ to the European private sector, and escalating economic warfare between the US and EU would clearly be a threat to that. The third factor is that the US-EU dispute over Greenland threatens to undermine the NATO alliance, meaning that security concerns could add to the confidence shock. The EU continues to rely on US support for Ukraine as well as the US security umbrella more generally, and this also looks increasingly at risk.

Protests in Iran and concerns about oil supply

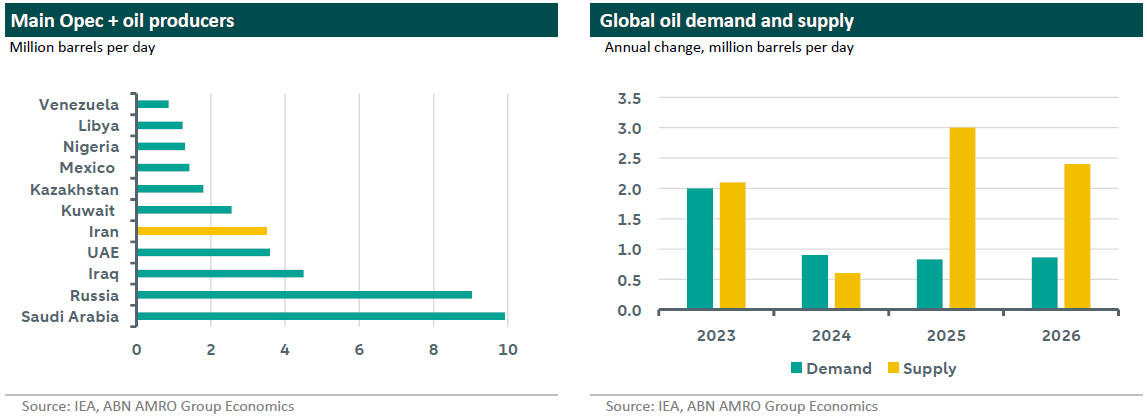

The widespread public protests in Iran against the regime, together with the possibility of US military intervention (a prospect that has recently receded) raised concerns recently about potential disruption to Iran’s oil supply. Iran is a significant producer (see chart below on the left), with supply of around 3.5 million barrels per day. It must be said that the starting point for the global oil market is very favourable (at least for consumers) with an ongoing supply glut expected this year, which should put downward pressure on prices. However, a scenario where Iran’s production was seriously disrupted could take the market closer to balance, or even one where demand exceeds supply, which could instead put upward pressure on prices.

Threats to Fed independence

The final risk to highlight is to the Fed’s independence. The central bank has received grand jury subpoenas from the Justice Department regarding Jerome Powell’s June congressional testimony about renovations at the Fed’s headquarters. Last year, it became apparent that the Trump administration viewed these renovations as a potential way to challenge Chair Powell. In a video statement immediately after the move, Powell emphasized that “the threat (…) is a consequence of the Federal Reserve setting interest rates based on our assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the President.” The first order risk from the attacks to the Fed’s independence is that it may raise concerns that it will follow an easier policy path than justified by the state of the economy. Running the economy hot might be seen as a positive in the short-term, but over the medium-to-long term it could raise inflation and lead to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, which may then require aggressive tightening to fix. As a result, longer term rates would start to rise. With US assets being the global risk-free benchmark, this repricing would spill over to all major economies, including Europe. It would also likely lead to a weaker dollar, and more generally put the US’ dominant role in the global financial system under pressure, even if no clear alternative exists.

However, at this stage, we see these risks as being contained. First of all, a subpoena marks the beginning of an evidence-gathering process. This is an investigation, which may conclude without charges. If an indictment does occur, it will likely follow the precedent set by the Lisa Cook case, likely reaching the Supreme Court and taking considerable time. If anything, this challenge to the Fed’s independence could prompt the FOMC to take a slightly more hawkish stance to defend the institution. Powell has responded forcefully, calling out the subpoena for what it is, i.e. a politically motivated plot to remove him.

The timing suggests this may relate to his potential continued presence on the Fed’s board of governors after his term as Chair ends, which is crucial for Trump’s influence over the board. This increases pressure on Powell to step down, but the strategy might backfire in a couple of ways. First, Powell may become more defiant and stay on the board precisely because of this. Second, it makes the appointment of the next Chair a lot more difficult. Given this blatant attack on Fed independence, any nominee will be even more clearly seen in this light. Accepting the role with these lawsuits ongoing effectively implies accepting the loss of independence. Any potential chair that accepts the role is therefore immediately compromised. This may slightly improve the chances for an outsider like Kevin Warsh, who could be viewed as more independent.